Born in the second half of the 19th century and celebrating his 90th birthday in the second half of the 20th century, the journalist and writer Arnold Ilyich Gessen believed “the watershed of… eras” to occur not in 1900 but instead in 1917, saying, “I spent forty years of my life in Imperial Russia, and another fifty as a citizen of the Soviet Union.”

The part of his life spent in “Imperial Russia” was connected with the house of his parents — the printer Ilya Alexandrovich Gessen and Yevdokia (Ida) Avraamovna Gessen. Arnold (Aaron) was the eldest of nine children. Gessen mentioned three of them in one of his letters in 1963, “My brother Abram Ilyich, associate professor at the Leningrad Institute, and two sisters, doctors… also graduated from the Korocha gymnasiums.”

Gessen met his future wife Mariya Yakovlevna Dolginover in 1914, which was still during his “first era”. She became not only his wife but also his faithful helper, and they stepped into the next era together. Their son Boris Arnoldovich (born in 1919) became an engineer, participated in the war, and for many years was a professor at the Moscow Machine and Tool Institute. Their daughter Dina Arnoldovna studied at the Maurice Thorez Institute of Foreign Languages, then in a medical school, she worked as a fashion designer and her father’s literary secretary.

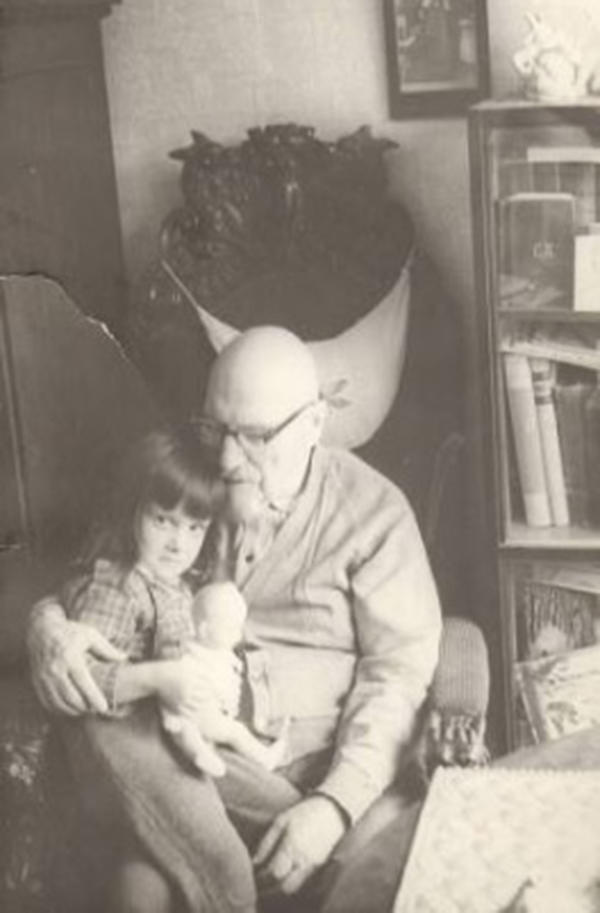

The photograph captured Yelena Viktorovna Kovalenko — Dina Arnoldovna’s daughter, who became a writer, translator, editor, and professor of the Russian language. In 2012, the Belgorod Literature Museum received from Yelena Kovalenko copies of the photographs and documents connected with Arnold Gessen’s family; in 2018, she donated the writer’s archive and some of his belongings.

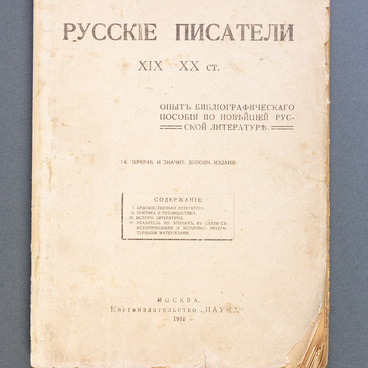

The archive, that Gessen meticulously sorted by date and theme, consisted of over three dozen boxes. It included a selection of materials about the work of Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin and photographic plates with his autographs; manuscripts of articles and scripts about Alexander Pushkin, the poets of the Pushkin era, Nikolay Nekrasov, Petrodvorets and Tsarskoye Selo, the Abramtsevo Museum and the Lenin library for “Diafilm” (Filmstrip) and the Central Television Studio in Moscow. The boxes also revealed a lot of periodical literature, congratulatory addresses, photographs, books, letters, and cassettes with recordings of the 90th birthday.

The part of his life spent in “Imperial Russia” was connected with the house of his parents — the printer Ilya Alexandrovich Gessen and Yevdokia (Ida) Avraamovna Gessen. Arnold (Aaron) was the eldest of nine children. Gessen mentioned three of them in one of his letters in 1963, “My brother Abram Ilyich, associate professor at the Leningrad Institute, and two sisters, doctors… also graduated from the Korocha gymnasiums.”

Gessen met his future wife Mariya Yakovlevna Dolginover in 1914, which was still during his “first era”. She became not only his wife but also his faithful helper, and they stepped into the next era together. Their son Boris Arnoldovich (born in 1919) became an engineer, participated in the war, and for many years was a professor at the Moscow Machine and Tool Institute. Their daughter Dina Arnoldovna studied at the Maurice Thorez Institute of Foreign Languages, then in a medical school, she worked as a fashion designer and her father’s literary secretary.

The photograph captured Yelena Viktorovna Kovalenko — Dina Arnoldovna’s daughter, who became a writer, translator, editor, and professor of the Russian language. In 2012, the Belgorod Literature Museum received from Yelena Kovalenko copies of the photographs and documents connected with Arnold Gessen’s family; in 2018, she donated the writer’s archive and some of his belongings.

The archive, that Gessen meticulously sorted by date and theme, consisted of over three dozen boxes. It included a selection of materials about the work of Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin and photographic plates with his autographs; manuscripts of articles and scripts about Alexander Pushkin, the poets of the Pushkin era, Nikolay Nekrasov, Petrodvorets and Tsarskoye Selo, the Abramtsevo Museum and the Lenin library for “Diafilm” (Filmstrip) and the Central Television Studio in Moscow. The boxes also revealed a lot of periodical literature, congratulatory addresses, photographs, books, letters, and cassettes with recordings of the 90th birthday.