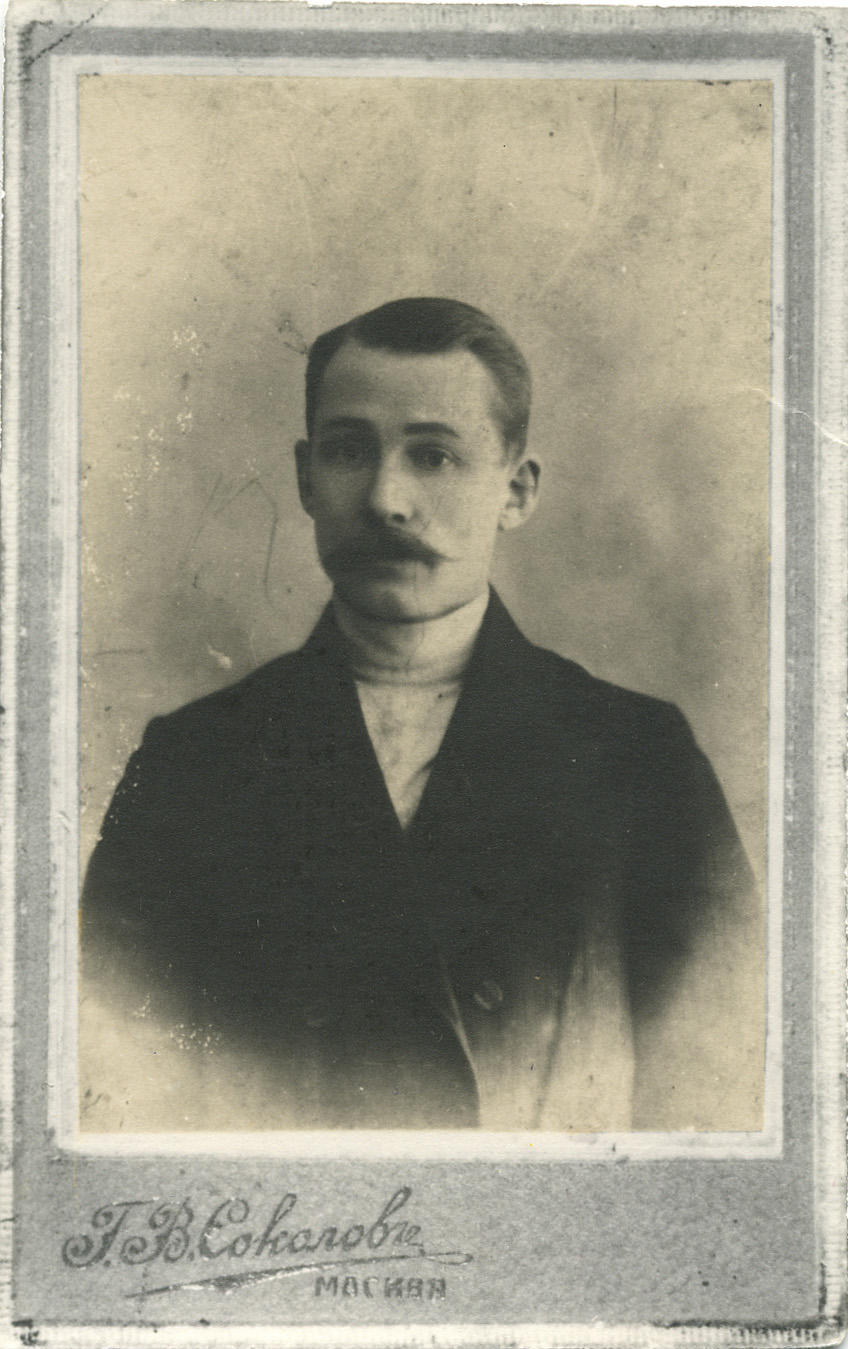

This photograph represents the poet’s parents — Alexander Nikitich and Tatiana Fedorovna Esenin with daughter Shura. The photograph was taken in 1912, when Sergei Esenin graduated from the Spas-Klepiki Teachers School and moved to Moscow. At first, he lived at his father’s place in the Strochenovsky Lane.

Alexander Esenin served in the butcher shop in Moscow since an age of twelve. He married to 16-year old Tatiana Titova in 1891. During this period, the poet’s father just paid short visits to the village. After revolution Alexander Nikitich returned to his native village and held a position of the Poor Peasants' Committee secretary. He died in 1931.

The mother of the future poet was “illiterate, having no passport”. When Sergei was a small child, “she took a job of a maid in Ryazan or worked at the confectionery plant in Moscow”. The poet himself in the autobiography drafts wrote that his “childhood was like that of all children from the village”. However, this phrase was omitted from the final text.

The poet addresses his mother with gentle lines in “A Letter to Mother” (1924). The “Сrushed Snow Сrumbles and Prickles…” (1925) and “The Dawn Calls the Other One…” (1925) were also dedicated to his mother. Tatiana Fedorovna took her son’s death in 1925 hard and throughout her life welcomed multiple admirers of his talent.

Of seven children born in the Yesenin family of only three survived: Sergei, Ekaterina, and Alexandra. Younger daughter Shura is also present on the photograph. She lived a long life and devoted herself to the care of the family and the memory of her brother. Alexandra initiated the opening if the poet’s museum in Konstantinovo and consulted on the problems of his life and creative work. She kept many books from the personal library of Sergei Esenin, his personal possessions and photographs and gave them to the Museum as token gift.

How nice then for me to recall

The overgrown pond, hoarse ring of the alder,

That there, somewhere, live my father and mother,

Who do not care for all my poems,

To whom I am dear, like a field, like flesh,

Like rain, that loosens the greens in spring.

They would come to pierce you with a pitchfork

For each insult of yours thrown at me…

Alexander Esenin served in the butcher shop in Moscow since an age of twelve. He married to 16-year old Tatiana Titova in 1891. During this period, the poet’s father just paid short visits to the village. After revolution Alexander Nikitich returned to his native village and held a position of the Poor Peasants' Committee secretary. He died in 1931.

The mother of the future poet was “illiterate, having no passport”. When Sergei was a small child, “she took a job of a maid in Ryazan or worked at the confectionery plant in Moscow”. The poet himself in the autobiography drafts wrote that his “childhood was like that of all children from the village”. However, this phrase was omitted from the final text.

The poet addresses his mother with gentle lines in “A Letter to Mother” (1924). The “Сrushed Snow Сrumbles and Prickles…” (1925) and “The Dawn Calls the Other One…” (1925) were also dedicated to his mother. Tatiana Fedorovna took her son’s death in 1925 hard and throughout her life welcomed multiple admirers of his talent.

Of seven children born in the Yesenin family of only three survived: Sergei, Ekaterina, and Alexandra. Younger daughter Shura is also present on the photograph. She lived a long life and devoted herself to the care of the family and the memory of her brother. Alexandra initiated the opening if the poet’s museum in Konstantinovo and consulted on the problems of his life and creative work. She kept many books from the personal library of Sergei Esenin, his personal possessions and photographs and gave them to the Museum as token gift.

He mentions his parents in the poem Confessions of a Hooligan (1920):

The overgrown pond, hoarse ring of the alder,

That there, somewhere, live my father and mother,

Who do not care for all my poems,

To whom I am dear, like a field, like flesh,

Like rain, that loosens the greens in spring.

They would come to pierce you with a pitchfork

For each insult of yours thrown at me…