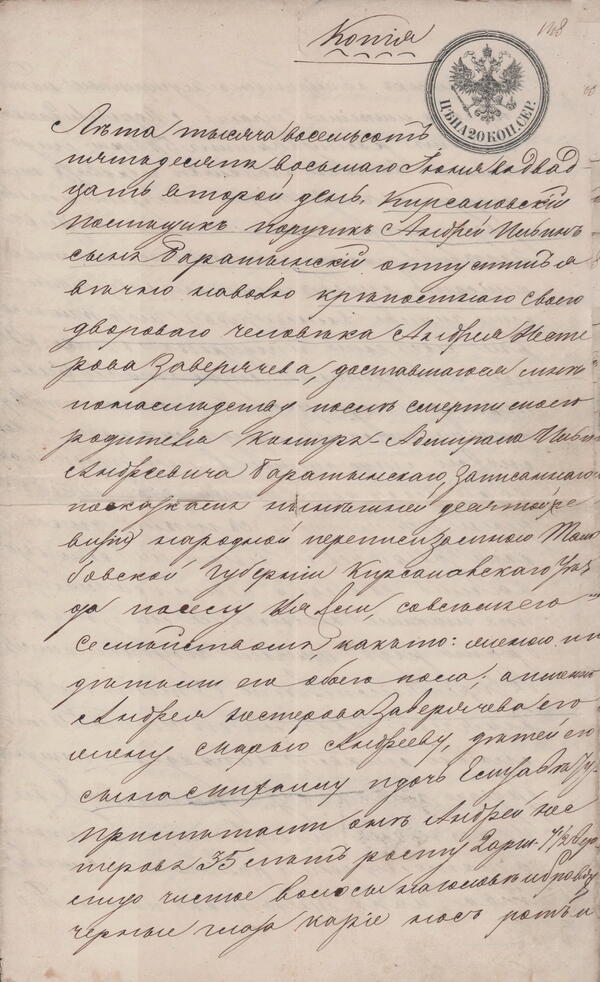

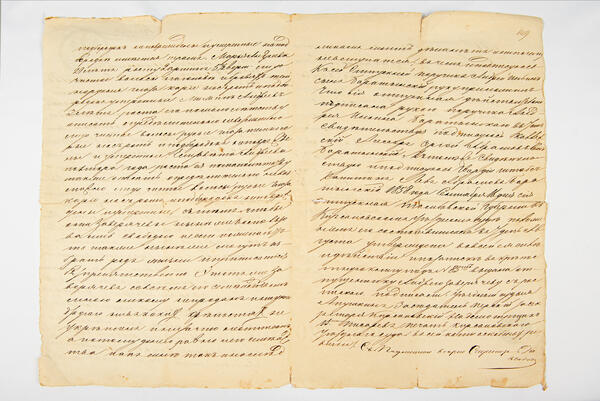

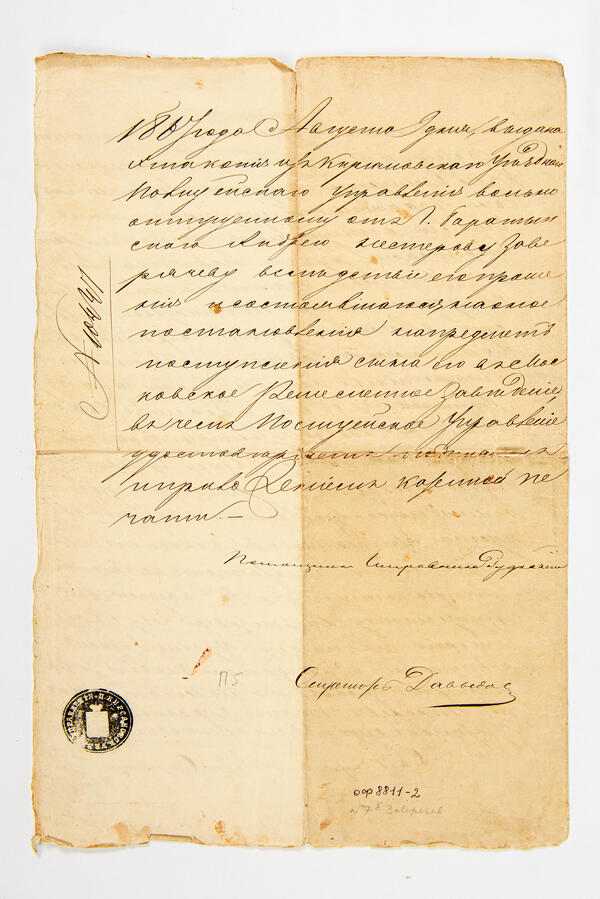

On June 22, 1858, the landowner Andrey Ilyich Boratynsky granted his serf Andrey Nesterovich Zaveryachev a letter of manumission, freeing him from serfdom. Nine years later, on August 9 1867, Andrey Nesterovich obtained a copy of his letter of manumission from the Kirsanov police department as his son wanted to study at the Moscow Vocational School. The original document is now on display at the Kirsanov Local History Museum.

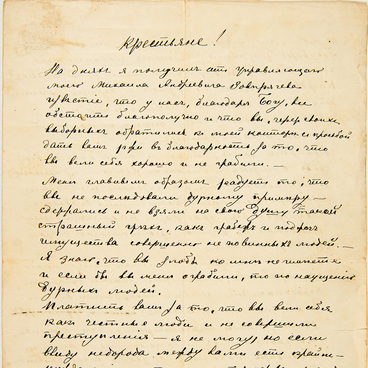

Andrey Nesterovich Zaveryachev served as a valet on the Boratynsky estate in Ilyinovka. When the servant was manumitted, he was appointed by the landlord to manage the estate. His wife and two children — Mikhail and Elizaveta — were mentioned in the letter, issued to Zaveryachev. Later he had seven more children. Two sons later became managers as well: Ivan Andreevich — in the Chicherins’ estate of Karaul, and Mikhail Andreevich — in Ilyinovka, succeeding his father in this capacity.

In the mid-19th century, the law of the Russian Empire stipulated that “serfdom is terminated either by the landlord’s will or by law”. Serf owners could manumit their peasants both leaving them landless or providing them with some land, under a wide range of conditions. According to the law, however, these conditions must not in any case be “restrictive to the freedom of the one being freed”. If a landlord wished to let his serf go free for some merits, he had to draw up a letter of manumission (volnaya). This document was issued in two ways: either by a title deed entering the data into the “tittle deeds book” (similar to the present notary’s certification of ownership rights) or by an individual at home. At home (as in the case of Alexander Nesterovich Zaveryachev), the letter of manumission was drawn up by the owner in the presence of two witnesses. The documents included the description of the freed person and his family members in every detail. Within a month, the freed peasant had to submit the letter for registration at the District Court or the Civic Chamber.

From the second half of the 18th century the number of serfs in Russia declined. In the 19th century, this was due to the recruitment of peasants into the army, the purchase of letters of manumission, and their change of estates, most often merchants. In 1856 serfs made up 37 per cent of the total population of the Russian Empire (A. G. Troinitsky, “On the number of serfs in Russia. St. Petersburg. 1858”).

Andrey Nesterovich Zaveryachev served as a valet on the Boratynsky estate in Ilyinovka. When the servant was manumitted, he was appointed by the landlord to manage the estate. His wife and two children — Mikhail and Elizaveta — were mentioned in the letter, issued to Zaveryachev. Later he had seven more children. Two sons later became managers as well: Ivan Andreevich — in the Chicherins’ estate of Karaul, and Mikhail Andreevich — in Ilyinovka, succeeding his father in this capacity.

In the mid-19th century, the law of the Russian Empire stipulated that “serfdom is terminated either by the landlord’s will or by law”. Serf owners could manumit their peasants both leaving them landless or providing them with some land, under a wide range of conditions. According to the law, however, these conditions must not in any case be “restrictive to the freedom of the one being freed”. If a landlord wished to let his serf go free for some merits, he had to draw up a letter of manumission (volnaya). This document was issued in two ways: either by a title deed entering the data into the “tittle deeds book” (similar to the present notary’s certification of ownership rights) or by an individual at home. At home (as in the case of Alexander Nesterovich Zaveryachev), the letter of manumission was drawn up by the owner in the presence of two witnesses. The documents included the description of the freed person and his family members in every detail. Within a month, the freed peasant had to submit the letter for registration at the District Court or the Civic Chamber.

From the second half of the 18th century the number of serfs in Russia declined. In the 19th century, this was due to the recruitment of peasants into the army, the purchase of letters of manumission, and their change of estates, most often merchants. In 1856 serfs made up 37 per cent of the total population of the Russian Empire (A. G. Troinitsky, “On the number of serfs in Russia. St. Petersburg. 1858”).