In 1753, Empress Elizaveta Petrovna, celebrating the tenth anniversary of her accession to the throne, visited the Lavra. A ceremonial service was held here in her honor and a festive dinner was given, followed by festive lights and fireworks. At the same time, a decree was issued “by Her Imperial Majesty… on the reconstruction of dilapidated items in the sacristy of this Lavra and other places.” In 1754, a precious cover for the Gospel was created.

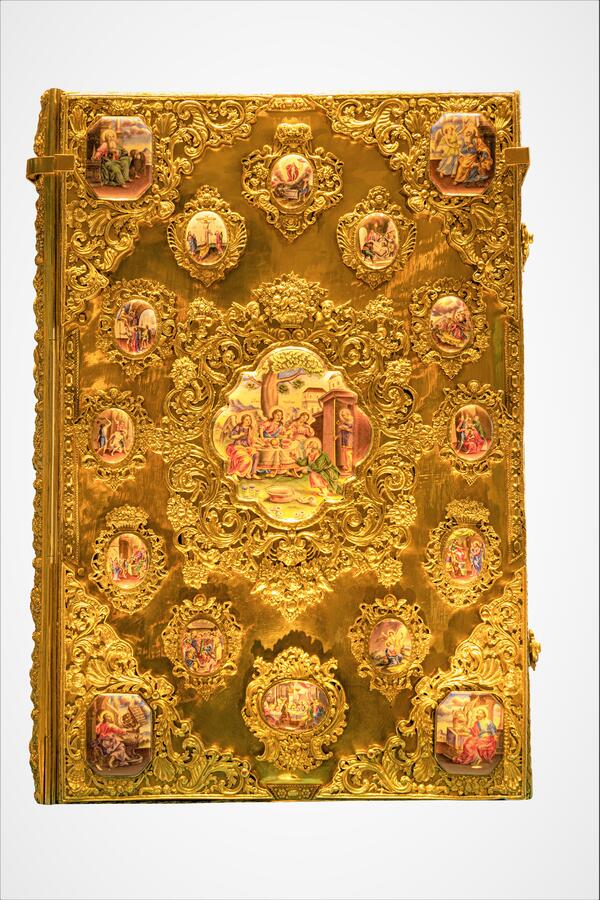

The Gospel itself was printed in Moscow in 1689. The cover was made of gilded silver, and the inside was lined with red silk. On the front board there is a “serednik” (the central decorative part), “naugolniks” (corner pieces) and 12 “drobnitsas” (decorative plaques) made in the technique of through-chasing with patterns of garlands, leaves, fruit bundles, flower pots. In the centers of these intricate cartouches-rosettes painted enamel plaques with the “Trinity of the Old Testament”, evangelists and “images of the Passion of Christ” were inserted. On the decorative plaques there are dates when they were created in: “1752” on the “Last Supper”, and “1751, October” on the central “Trinity”.

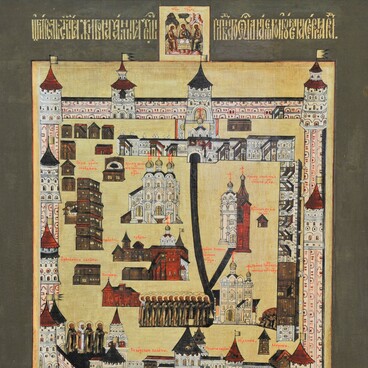

The reverse side of the Gospel book is no less spectacular. The “image of the Jesse Tree” is stamped on it — an allegorical image of the family tree of Jesus Christ, and the Mother of God of Vladimir and the prophets are finely “painted” with enamel paints.

In the Lavra documents it is noted that all the images “were painted on the enamel by the most notable pictorial work”. Hieromonk Pavel Kazanovich, who came from the Kiev-Mezhyhirsky Monastery, taught art, including enamel miniature to Lavra masters, as well as students of the Trinity Seminary. Lavra craftsmen created small painted masterpieces with the scenes from the Holy Scriptures, which decorated not only the Gospel books, but also other objects of liturgical practice.

Written sources of the middle of the 18th century report that “this Gospel is all arranged from the sacristy treasury, ” that is, its production was financed entirely from the monastery funds. The cover is not branded, and this fact may mean that the thing was made in the monastery itself or, as they wrote then, “by homework.” Several silversmiths constantly worked at the monastery, they cleaned things in the sacristy, repaired broken utensils, made permanent household items from precious metals. In special cases, masters-virtuosos were called from among the monastic peasants who were released to Moscow “to feed themselves” from their craft. One of these silversmiths made this cover. His name remains unknown.

The Gospel itself was printed in Moscow in 1689. The cover was made of gilded silver, and the inside was lined with red silk. On the front board there is a “serednik” (the central decorative part), “naugolniks” (corner pieces) and 12 “drobnitsas” (decorative plaques) made in the technique of through-chasing with patterns of garlands, leaves, fruit bundles, flower pots. In the centers of these intricate cartouches-rosettes painted enamel plaques with the “Trinity of the Old Testament”, evangelists and “images of the Passion of Christ” were inserted. On the decorative plaques there are dates when they were created in: “1752” on the “Last Supper”, and “1751, October” on the central “Trinity”.

The reverse side of the Gospel book is no less spectacular. The “image of the Jesse Tree” is stamped on it — an allegorical image of the family tree of Jesus Christ, and the Mother of God of Vladimir and the prophets are finely “painted” with enamel paints.

In the Lavra documents it is noted that all the images “were painted on the enamel by the most notable pictorial work”. Hieromonk Pavel Kazanovich, who came from the Kiev-Mezhyhirsky Monastery, taught art, including enamel miniature to Lavra masters, as well as students of the Trinity Seminary. Lavra craftsmen created small painted masterpieces with the scenes from the Holy Scriptures, which decorated not only the Gospel books, but also other objects of liturgical practice.

Written sources of the middle of the 18th century report that “this Gospel is all arranged from the sacristy treasury, ” that is, its production was financed entirely from the monastery funds. The cover is not branded, and this fact may mean that the thing was made in the monastery itself or, as they wrote then, “by homework.” Several silversmiths constantly worked at the monastery, they cleaned things in the sacristy, repaired broken utensils, made permanent household items from precious metals. In special cases, masters-virtuosos were called from among the monastic peasants who were released to Moscow “to feed themselves” from their craft. One of these silversmiths made this cover. His name remains unknown.