The director spent two years filming BEzhin Meadow (from 1935 to 1937) and had two versions of the movie. However, both were censored and banned as ‘ideologically faulty as well as infected with mysticism and formalism’ and subsequently destroyed.

The movie is based on a true story involving PAvlik MorOzov, a teenager who died in 1932. Pavlik’s father, who had supposedly been helping the kulAks (wealthy peasants), was charged in his death. Shortly before he died, the boy had snitched on his father to the authorities. The Soviet propaganda used this fact to try and fabricate a myth about a selfless young Pioneer (a member of the Soviet youth organization) who put the interests of the state before his family bonds. But Eisenstein set about directing the movie because he saw this incident as a historical tragedy: rapid social changes led to a breakdown of family relationships.

The screenplay was created by playwright Alexander Rzhevsky. He changed the protagonist’s name from Pavlik to Stepok and transferred the events from Northern Urals to Bezhin Meadow mentioned in Sketches from a Hunter’s Album by Ivan Turgenev. In doing so, he wanted to highlight the contrast between the upright children of state farmers, members of the Soviet Youth Organization, and the superstitious children of the 19th-century peasant serfs. In Eisenstein’s movie, the father resembles the pagan god Pan from Mikhail Vrubel’s painting. He is not an affluent peasant but rather a poor man with a mindset typical for the patriarchal community-based society of Russian villages. His son, on the contrary, personifies youth Bartholomew (who will later become St. Sergius of Radonezh) from the Vision to the Youth Bartholomew, a painting by Mikhail Nesterov. The son quells violence as if he traveled back in time from some ideal future. And both, the father and the son, end up dying in the class warfare of the era. In the 1930s, such a tragic interpretation was bound to be banned. Eisenstein himself narrowly avoided being arrested.

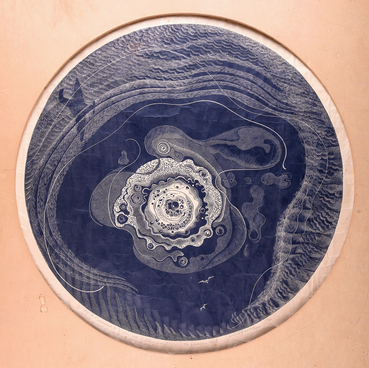

This photo was on the wall of Eisenstein’s bedroom, in his apartment on Potylikha Street where he lived from 1935 to 1948. The picture shows a young podkulAchnik (a political label used in the Soviet Union in the 1920s and 1930s to brand people considered traitors to the Soviet government). He is being led onto the porch of a church where three opponents of collectivization (a policy of forced consolidation of individual peasant households into collective farms), who had attempted to set fire to the collective farm fields, had been hiding. And the severe-looking old woman, named StyOpka, is making the sign of the cross over him. This episode was shot in a church in the village of Troitse-Golenishchevo, not far from the Mosfilm movie studio. The photo was taken by Mikhail Gomorov, who used to play in the productions staged by Eisenstein at the Proletkult theater, and had been his assistant ever since the Strike.

The movie is based on a true story involving PAvlik MorOzov, a teenager who died in 1932. Pavlik’s father, who had supposedly been helping the kulAks (wealthy peasants), was charged in his death. Shortly before he died, the boy had snitched on his father to the authorities. The Soviet propaganda used this fact to try and fabricate a myth about a selfless young Pioneer (a member of the Soviet youth organization) who put the interests of the state before his family bonds. But Eisenstein set about directing the movie because he saw this incident as a historical tragedy: rapid social changes led to a breakdown of family relationships.

The screenplay was created by playwright Alexander Rzhevsky. He changed the protagonist’s name from Pavlik to Stepok and transferred the events from Northern Urals to Bezhin Meadow mentioned in Sketches from a Hunter’s Album by Ivan Turgenev. In doing so, he wanted to highlight the contrast between the upright children of state farmers, members of the Soviet Youth Organization, and the superstitious children of the 19th-century peasant serfs. In Eisenstein’s movie, the father resembles the pagan god Pan from Mikhail Vrubel’s painting. He is not an affluent peasant but rather a poor man with a mindset typical for the patriarchal community-based society of Russian villages. His son, on the contrary, personifies youth Bartholomew (who will later become St. Sergius of Radonezh) from the Vision to the Youth Bartholomew, a painting by Mikhail Nesterov. The son quells violence as if he traveled back in time from some ideal future. And both, the father and the son, end up dying in the class warfare of the era. In the 1930s, such a tragic interpretation was bound to be banned. Eisenstein himself narrowly avoided being arrested.

This photo was on the wall of Eisenstein’s bedroom, in his apartment on Potylikha Street where he lived from 1935 to 1948. The picture shows a young podkulAchnik (a political label used in the Soviet Union in the 1920s and 1930s to brand people considered traitors to the Soviet government). He is being led onto the porch of a church where three opponents of collectivization (a policy of forced consolidation of individual peasant households into collective farms), who had attempted to set fire to the collective farm fields, had been hiding. And the severe-looking old woman, named StyOpka, is making the sign of the cross over him. This episode was shot in a church in the village of Troitse-Golenishchevo, not far from the Mosfilm movie studio. The photo was taken by Mikhail Gomorov, who used to play in the productions staged by Eisenstein at the Proletkult theater, and had been his assistant ever since the Strike.