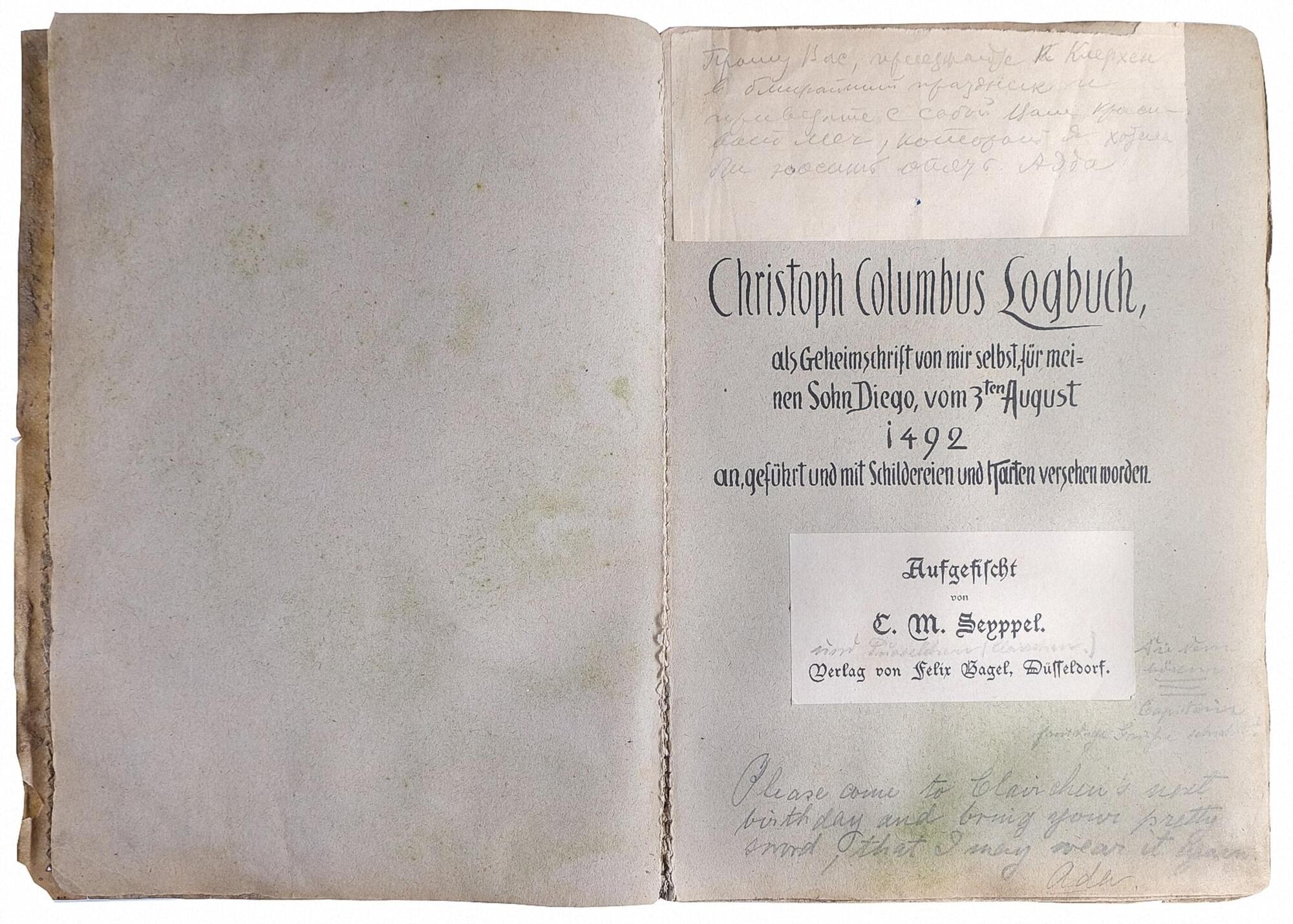

Half a century later, other journalists tried to resolve the mystery. It was Dmitry Dyomin who succeeded. At first, studying only the slide images, he thought that the book was handwritten. But during the research, Dyomin noticed that the white cardboard title page had a clumsily written inscription: “C. M. Seyppel. Felix Bagel Publishing House. Dusseldorf”. He then decided to check the information about a similar printed publication in the Union Catalog of American Libraries. There he found the author of the book, Carl Seyppel, with a reference to “The Diary”, “The color and appearance of paper and binding imitate those of a book damaged by seawater. The publisher’s imprint is on a separate piece of cardboard. Published in 1890.” The diary turned out to be not a fake or a hoax but simply a practical joke by a talented artist and writer.

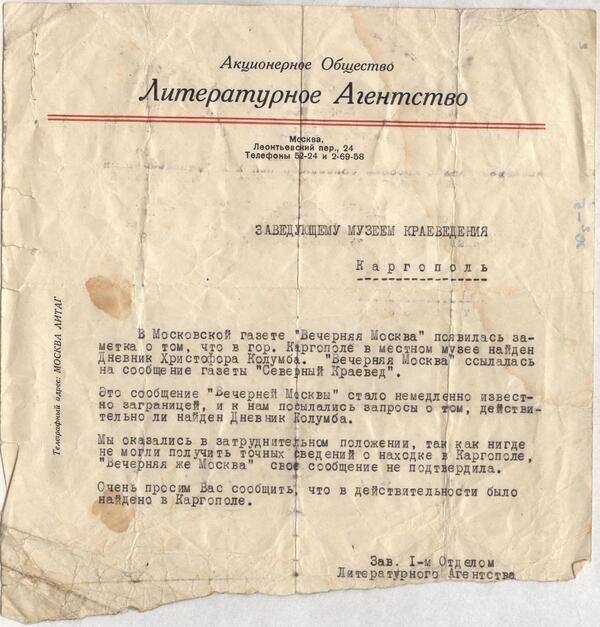

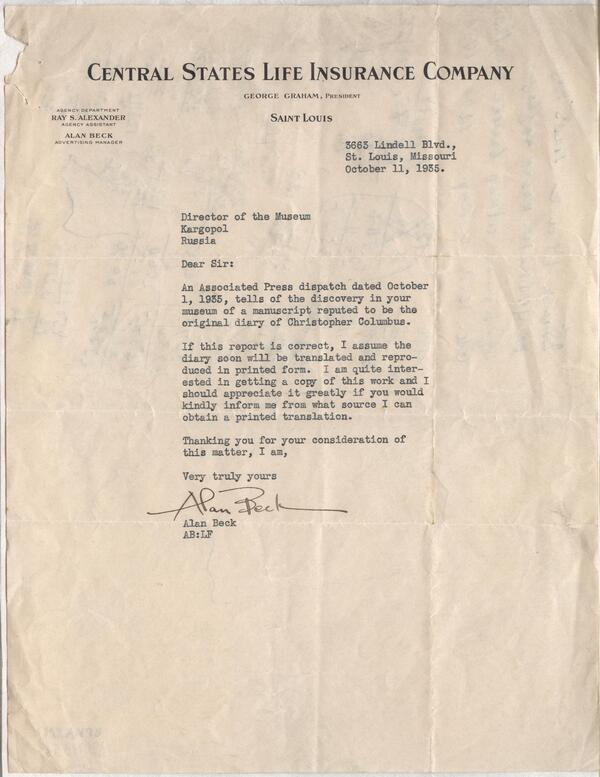

Later, the story of how the book ended up in the museum was revealed from the notes of the Solovetsky camp doctor, published in the book “Treasures of the Gulag”. The prisoners trusted the doctor with their innermost secrets, and one day a prisoner from Kargopol told him about the book.

It turned out that the first owner of the publication was a local rural psalm reader. Once he ran away from home and became a sailor. In one of his travels, he bought a book in a second-hand bookseller’s shop in Hamburg. The man learned German and read the book in moments of rest. He could even reproduce some lines from memory. The sailor returned to Kargopol on the eve of the revolution and, anticipating his arrest, left his favorite thing to Kapiton Kolpakov for safekeeping.