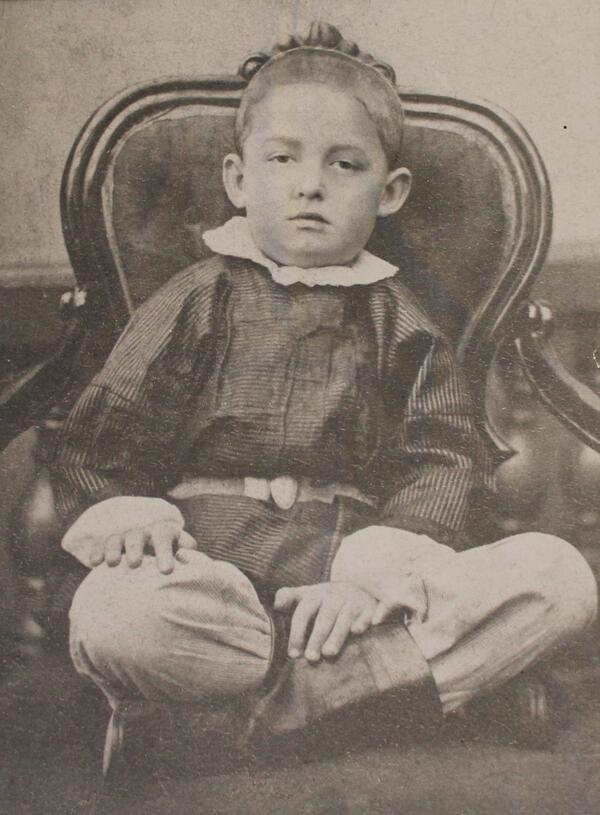

The photograph kept in the museum of Tsiolkovsky depicts Konstantin Tsiolkovsky at the age of 5 or 6. The original photo was taken in 1863-1864 in Ryazan by the Blum brothers. The reproduction was created by photographer V. ShimAkin in 1967.

According to the family legend, the Tsiolkovsky family comes from the lineage of the rebel Nalivaiko. He fought against the Polish aristocracy, led a peasant-Cossack rebellion and was executed in 1597. However, no documents have been found to confirm or refute this relationship.

Archival documents show that the Tsiolkovsky family belonged to the Polish nobility. The first mention of this was found in documents from 1697. The father of the future scientist, Edward Tsiolkovsky, graduated from the Petersburg Forestry Institute, served in Olonets and Petersburg governorates. In 1843, he was transferred to the Ryazan governorate to the position of a forester, and a few years later he settled in Izhevskoye. Izhevskoye at this time was considered the economic and cultural center of the whole district. It had a population of about 8,000, three parish churches, many shops, public houses, tea houses and couching inns. Mother of the future scientist was the daughter of the retired captain - Maria Tsiolkovskaya, née Yumasheva.

Konstantin Tsiolkovsky wrote about his birth: ‘The weather was fine but cold on September 4, 1857. My mother took my two older brothers, six and five years old, and went for a walk with them… came back… the next day there was a new citizen of the universe Konstantin Tsiolkovsky’.

As a child, the ‘citizen of the universe’ dreamed of the sky and flight. He liked to watch birds, climb trees and fences, jump from high up. He also wanted to learn how to fly. Later, Tsiolkovsky wrote in her memoirs: ‘I was amazed by the cart on wheels, because the slightest effort set into motion. <…> I flew kites and launched a cockroach high up in a box on a thread. <…> In winter we tried… to make skates from wire. I made them, but I crashed down on the ice so bad that the sparks were flying out of my eyes… and I took out the real broken skates, fixed them and learned to skate in one day. <…> The toys were inexpensive, but I simply had to take them apart to see what was inside them’.

According to the family legend, the Tsiolkovsky family comes from the lineage of the rebel Nalivaiko. He fought against the Polish aristocracy, led a peasant-Cossack rebellion and was executed in 1597. However, no documents have been found to confirm or refute this relationship.

Archival documents show that the Tsiolkovsky family belonged to the Polish nobility. The first mention of this was found in documents from 1697. The father of the future scientist, Edward Tsiolkovsky, graduated from the Petersburg Forestry Institute, served in Olonets and Petersburg governorates. In 1843, he was transferred to the Ryazan governorate to the position of a forester, and a few years later he settled in Izhevskoye. Izhevskoye at this time was considered the economic and cultural center of the whole district. It had a population of about 8,000, three parish churches, many shops, public houses, tea houses and couching inns. Mother of the future scientist was the daughter of the retired captain - Maria Tsiolkovskaya, née Yumasheva.

Konstantin Tsiolkovsky wrote about his birth: ‘The weather was fine but cold on September 4, 1857. My mother took my two older brothers, six and five years old, and went for a walk with them… came back… the next day there was a new citizen of the universe Konstantin Tsiolkovsky’.

As a child, the ‘citizen of the universe’ dreamed of the sky and flight. He liked to watch birds, climb trees and fences, jump from high up. He also wanted to learn how to fly. Later, Tsiolkovsky wrote in her memoirs: ‘I was amazed by the cart on wheels, because the slightest effort set into motion. <…> I flew kites and launched a cockroach high up in a box on a thread. <…> In winter we tried… to make skates from wire. I made them, but I crashed down on the ice so bad that the sparks were flying out of my eyes… and I took out the real broken skates, fixed them and learned to skate in one day. <…> The toys were inexpensive, but I simply had to take them apart to see what was inside them’.