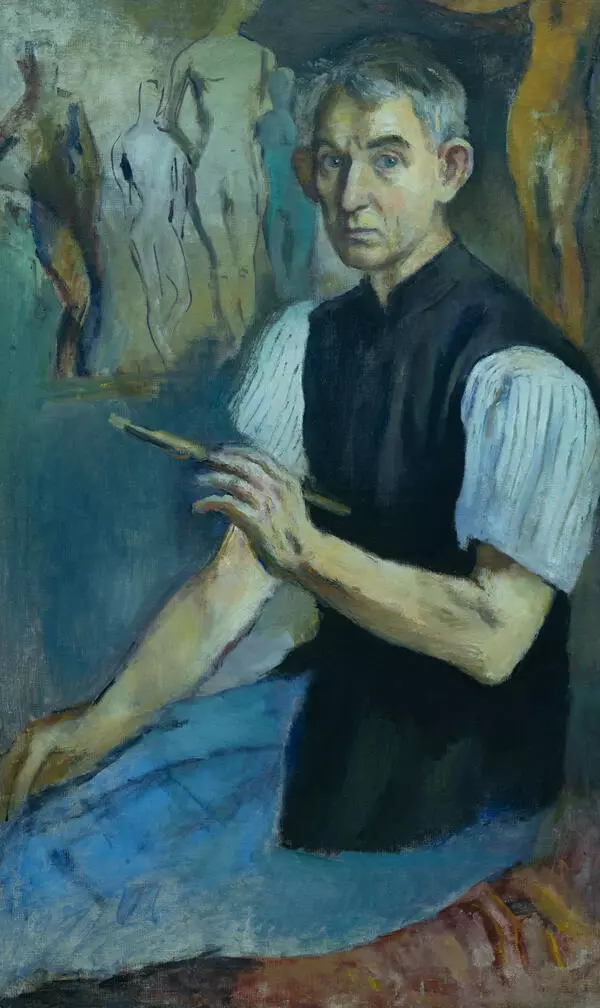

Ivan Vasilyevich Dmitriyev received an art education in Moscow and spent his mature years there, but he was actually born in a Chuvash village, and themes related to his homeland, as well as its customs and traditions, stayed with him always.

As a child, Dmitriyev attended real Chuvash weddings first in Mataki and then in Lashch-Tayaba, after his parents had moved there in 1926. Each of them made a strong impression on the artist with its tunefulness and the guests’ colorful outfits. The characters in the painting are dressed in the costumes of the lower Chuvash, who resided in Ivan Dmitriyev’s native lands. The center of the composition is naturally reserved for the bride and groom. As for the groom’s image, Dmitriyev forgoes historical accuracy (at the wedding, the groom almost never takes off his headdress — a hat with a coin sewn in the center) and depicts his favorite male type — tall, thin, with an almost boyish figure and curly blond hair.

Following the tradition, the couple stands modestly, they neither drink nor dance. The youngest best man, on the contrary, is having a great time dancing. He performs the squat dance, waving a dance kerchief. Such a kerchief, densely embroidered around the perimeter and in the center, was passed from one wedding to another and usually became pretty worn out in the middle. The kerchief made the dance especially expressive; it also helped the dancer to share their energy with those around and gave protection from any hostile, maybe even malevolent, glare. It is worth mentioning that, according to Chuvash beliefs, a wedding is not just a celebration — it is the place where two worlds collide.

The best man is wearing a woman’s apron on his back. According to tradition, the groom’s friends put on elements of the costume that the women of their family wore, such as jewelry, garter belts, or aprons, as is seen in the picture, to protect themselves from the evil eye. The idea was to wear them in any but intended way.

In the upper part of the painting, under the ceiling, there are icons in the so-called red or sacred corner. There is nothing accidental about them being in the painting. In the early version and preparatory sketches, there was no red corner. Ivan Dmitriyev’s family was deeply religious: his father was a priest, and therefore faith was an indispensable part of the artist’s life. But he never ceased to be amazed at how people managed to combine Eastern Orthodoxy and their pagan rites, traditions, and superstitions. In this painting, important ritual events take place alongside everyday ones: a mother feeds her baby, a child helps himself to a festive delicacy, and a dog runs inside from the yard. This is how Ivan Dmitriyev saw weddings — cheerful, bright, loud and full of life.

As a child, Dmitriyev attended real Chuvash weddings first in Mataki and then in Lashch-Tayaba, after his parents had moved there in 1926. Each of them made a strong impression on the artist with its tunefulness and the guests’ colorful outfits. The characters in the painting are dressed in the costumes of the lower Chuvash, who resided in Ivan Dmitriyev’s native lands. The center of the composition is naturally reserved for the bride and groom. As for the groom’s image, Dmitriyev forgoes historical accuracy (at the wedding, the groom almost never takes off his headdress — a hat with a coin sewn in the center) and depicts his favorite male type — tall, thin, with an almost boyish figure and curly blond hair.

Following the tradition, the couple stands modestly, they neither drink nor dance. The youngest best man, on the contrary, is having a great time dancing. He performs the squat dance, waving a dance kerchief. Such a kerchief, densely embroidered around the perimeter and in the center, was passed from one wedding to another and usually became pretty worn out in the middle. The kerchief made the dance especially expressive; it also helped the dancer to share their energy with those around and gave protection from any hostile, maybe even malevolent, glare. It is worth mentioning that, according to Chuvash beliefs, a wedding is not just a celebration — it is the place where two worlds collide.

The best man is wearing a woman’s apron on his back. According to tradition, the groom’s friends put on elements of the costume that the women of their family wore, such as jewelry, garter belts, or aprons, as is seen in the picture, to protect themselves from the evil eye. The idea was to wear them in any but intended way.

In the upper part of the painting, under the ceiling, there are icons in the so-called red or sacred corner. There is nothing accidental about them being in the painting. In the early version and preparatory sketches, there was no red corner. Ivan Dmitriyev’s family was deeply religious: his father was a priest, and therefore faith was an indispensable part of the artist’s life. But he never ceased to be amazed at how people managed to combine Eastern Orthodoxy and their pagan rites, traditions, and superstitions. In this painting, important ritual events take place alongside everyday ones: a mother feeds her baby, a child helps himself to a festive delicacy, and a dog runs inside from the yard. This is how Ivan Dmitriyev saw weddings — cheerful, bright, loud and full of life.