Nikita Kuzmich Sverchkov is one of the founders of professional painting in Chuvashia. The artist was born in 1891 in the village of Yanshikhovo-Norvashi, Kazan Governorate. He graduated from the Kazan Art School, where he studied under Nikolai Ivanovich Fechin. In 1912, he entered the Higher Art School at the Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg to study in the studio of Professor Dmitry Nikolayevich Kardovsky.

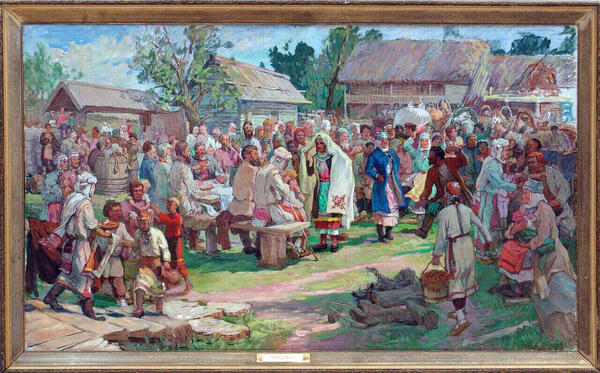

The painting “Chuvash Wedding” is a multifigure composition dedicated to the high point of the event, when, according to tradition, the bride sings a farewell song upon leaving her home and family. The number of preparatory sketches testifies to how persistently the artist searched for the most expressive composition, trying to make the image of the bride become the focal point of the painting. At the same time, he wanted to reflect the unique Chuvash wedding traditions and the variety of guests. In all that he succeeded. The circular composition sets a certain sequence for the viewer to study the entire pictorial space.

The Chuvash wedding usually lasted for several days. It began almost at the same time in the homes of both the groom and the bride. The painting depicts the yard of the bride’s wealthy parents with many outbuildings. The bride, saying goodbye to her dear parents, sings a sad song and brings them a kovsh (a Russian ladle) of ritual beer, where they, in turn, put a silver coin or a small silver piece of jewelry, which will belong to the bride after the wedding. In the center of the composition, the most respected members of the village community sit at the wedding table. On the table, there are mainly ritual dishes that symbolize abundance and fertility — bread, porridge, eggs — and drinks, which include moonshine, “arekh”, and beer brewed specially for the event. For the rest of the guests, a barrel of beer has been placed near the gate. Wooden ladles hang on it to make the drinking more convenient. On the right, the in-laws dance and praise the young by signing nursery rhymes; the relatives attend to the guests by distributing beer and refreshments. The ubiquitous children sit on the fence like sparrows. The dust from the wedding procession of the groom, who is on his way to meet the bride, swirls in the distance.

The artist fondly depicts the beauty of embroidered dresses, the shimmering of silver jewelry, the brilliance of the sun, the greenery of the grass and trees surrounding the yard, the two-story barns, and the carved gates. But all this vividness is just a camouflage for a more practical arrangement: a wedding in the early 20th century was still viewed as a way to organize economic affairs rather than the formalization of the relationship between two people who loved each other.

The painting “Chuvash Wedding” is a multifigure composition dedicated to the high point of the event, when, according to tradition, the bride sings a farewell song upon leaving her home and family. The number of preparatory sketches testifies to how persistently the artist searched for the most expressive composition, trying to make the image of the bride become the focal point of the painting. At the same time, he wanted to reflect the unique Chuvash wedding traditions and the variety of guests. In all that he succeeded. The circular composition sets a certain sequence for the viewer to study the entire pictorial space.

The Chuvash wedding usually lasted for several days. It began almost at the same time in the homes of both the groom and the bride. The painting depicts the yard of the bride’s wealthy parents with many outbuildings. The bride, saying goodbye to her dear parents, sings a sad song and brings them a kovsh (a Russian ladle) of ritual beer, where they, in turn, put a silver coin or a small silver piece of jewelry, which will belong to the bride after the wedding. In the center of the composition, the most respected members of the village community sit at the wedding table. On the table, there are mainly ritual dishes that symbolize abundance and fertility — bread, porridge, eggs — and drinks, which include moonshine, “arekh”, and beer brewed specially for the event. For the rest of the guests, a barrel of beer has been placed near the gate. Wooden ladles hang on it to make the drinking more convenient. On the right, the in-laws dance and praise the young by signing nursery rhymes; the relatives attend to the guests by distributing beer and refreshments. The ubiquitous children sit on the fence like sparrows. The dust from the wedding procession of the groom, who is on his way to meet the bride, swirls in the distance.

The artist fondly depicts the beauty of embroidered dresses, the shimmering of silver jewelry, the brilliance of the sun, the greenery of the grass and trees surrounding the yard, the two-story barns, and the carved gates. But all this vividness is just a camouflage for a more practical arrangement: a wedding in the early 20th century was still viewed as a way to organize economic affairs rather than the formalization of the relationship between two people who loved each other.