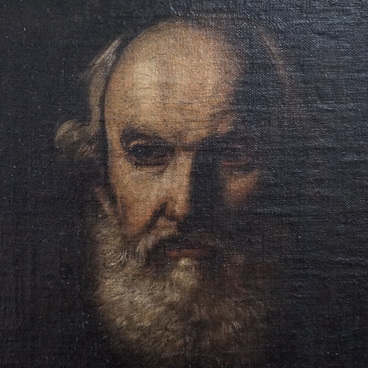

Tea started to be consumed on a massive scale in Russia in the first half of the 17th century. Porcelain gradually became an integral part of Russian tea drinking. The porcelain mug from the collection of the Arzamas museum belonged to Alexander Stupin, the founder of the first provincial school of painting, an artist and a teacher from Arzamas.

As far back as 1618, Chinese envoys gifted a few crates of tea to Tsar Michael Romanov. According to some recollections, this is how Fiodor Baikov, a statesman and traveller of the 17th century, drank it in 1654: ‘tea boiled with cow’s milk and butter’; this matter-of-factness could make one ‘conclude that Baikov was talking about something quite well-known’.

In Russia, tea became popular primarily as a medicinal beverage, and soon people started to drink it for pleasure as well. By the middle of the 17th century, it had become possible to buy up to 10 varieties of tea in Moscow. In 1679, the government signed an agreement with China on regular shipments of the drink. All the tealeaves imported from the Orient went to Moscow where they were sold together with other goods, and despite the high price, a lot of people were willing to buy tea.

Tea consumption was rising rapidly in Russia. By the 19th century, it was drunk by people from all the social strata. The statistics for 1830–1840 revealed that in the regions where tea was drunk in larger volumes people consumed smaller quantities of strong alcoholic drinks.

Tea drinking in rich noble, merchant and bourgeois families always involved porcelain ware. Russian porcelain also referred to pieces of pottery and majolica produced in Russia from the middle of the 18th century. Art historians consider this period to be one of the most important in the Russian decorative arts. The principal supplier of porcelain was the Imperial Porcelain Factory opened in the capital in 1744.

As far back as 1618, Chinese envoys gifted a few crates of tea to Tsar Michael Romanov. According to some recollections, this is how Fiodor Baikov, a statesman and traveller of the 17th century, drank it in 1654: ‘tea boiled with cow’s milk and butter’; this matter-of-factness could make one ‘conclude that Baikov was talking about something quite well-known’.

In Russia, tea became popular primarily as a medicinal beverage, and soon people started to drink it for pleasure as well. By the middle of the 17th century, it had become possible to buy up to 10 varieties of tea in Moscow. In 1679, the government signed an agreement with China on regular shipments of the drink. All the tealeaves imported from the Orient went to Moscow where they were sold together with other goods, and despite the high price, a lot of people were willing to buy tea.

Tea consumption was rising rapidly in Russia. By the 19th century, it was drunk by people from all the social strata. The statistics for 1830–1840 revealed that in the regions where tea was drunk in larger volumes people consumed smaller quantities of strong alcoholic drinks.

Tea drinking in rich noble, merchant and bourgeois families always involved porcelain ware. Russian porcelain also referred to pieces of pottery and majolica produced in Russia from the middle of the 18th century. Art historians consider this period to be one of the most important in the Russian decorative arts. The principal supplier of porcelain was the Imperial Porcelain Factory opened in the capital in 1744.