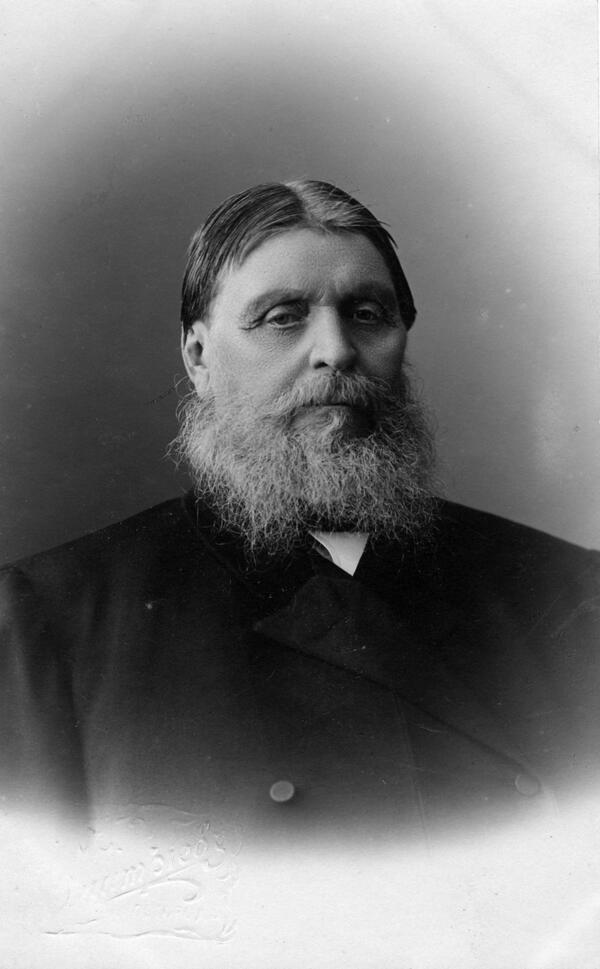

The square is overlooked by the former City Duma, once the main building in the city, with the city coat of arms depicting a deer on the facade. This was the Palace of Labor back in Soviet times. But in the 19th century, there stood a three-story tenement building that belonged to Pyotr Yegorovich Bugrov. The first floor was occupied by trading stalls, and the second floor was leased out to the city theater.

At the end of the 19th century, Bugrov’s grandson donated the tenement building to the City Duma under the condition that “this house is never to be used as any theater and entertainment establishment, especially a commercial establishment for selling strong alcoholic beverages. And any proceeds from it should go to a special fund for helping poor citizens.”

However, in 1898, the building was burned to the ground. The following year it was decided to erect a building for the meetings of the City Duma. The project was entrusted to the Moscow architect Vladimir Petrovich Zeidler. He faced a difficult task: he had to accommodate in one building the City Duma, its executive body — the city administration — and stores on the first floor, facing Bolshaya Pokrovskaya Street. The foundation was laid on September 12, 1901.

The great hall of the Duma building catches the eye with its elaborate wooden decorations. It is worth mentioning that both the doors and the wooden elements of the decor were originally part of the Tsar’s Pavilion at the All-Russia Exhibition in Nizhny Novgorod in 1896.

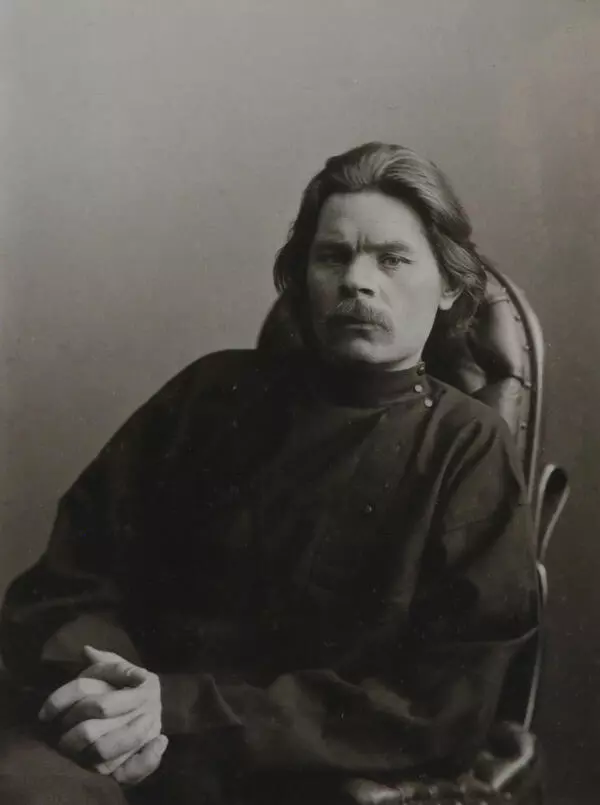

The interiors of the Tsar’s Pavilion were designed by the architect of the imperial court Robert Friedrich Melzer. All details were made of expensive and then-fashionable wood — rosewood and walnut. Nicholas II praised the Tsar’s Pavilion and donated it to the city as a token of gratitude. This was a truly royal gift: the pavilion cost 30,000 silver rubles. At a meeting of the City Duma in August 1896, Finance Minister Sergei Yulyevich Witte solemnly announced “His Imperial Majesty’s highest grace on the donation of the Tsar’s Pavilion to Nizhny Novgorod”.

But the years passed, and the city Duma could not

find a way to use the emperor’s gift: one day they wanted to establish courses

for teachers in the building, then the next day they would decide to organize a

museum of education. In the meantime, the pavilion began to deteriorate. One

might say that the architect Vladimir Zeidler saved it. He proposed to use the

preserved decor of the Tsar’s Pavilion to adorn the mayor’s office and the

grand halls of the City Duma building. This idea was unanimously supported by

the Duma: