The semantron is an ancient signaling instrument. When it was struck with a stick or a special mallet, it made a sound similar to the ringing of a bell.

This instrument has a long history. In the first centuries of Christianity in the Roman Empire, residents of cities and villages were summoned by alarm instruments — wooden or metal planks. In Russia, the semantron also predated the invention of bells. It notified residents of fires, enemy attacks, or other disasters. The semantron could also be used instead of a church bell: it summoned parishioners for matins, vespers, and feast rites.

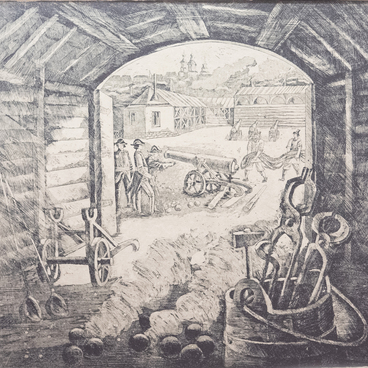

During the reign of Peter the Great, semantrons appeared at shipyards and Petrovsky Plant. They replaced the huge bells, which had been removed and melted down into cannons. A semantron was used to signal the beginning and the end of the work.

The instrument was made in the form of a cast-iron board, which had the shape of a bell, with a relief image. There was a round hole in the upper part of the instrument — this hole was used to suspend it from a crossbar.

Semantrons were produced from rolled sheet metal: it is more homogeneous and dense compared to the cast bell. The sound was clear and long — it lasted for 1–2 minutes, while the ringing of good bells could be heard for 10–30 seconds, depending on the weight and the quality of the metal. Semantrons have a lower sound than bells. Striking a semantron, the player chooses the place of impact, thereby changing not the pitch, but the timbre. By striking different areas, one can play a simple melody.

According to experts, the Orthodox tradition of using wooden and metal semantrons is going to exist for a long time. The Statute of the Church Bell of the Russian Orthodox Church, which was approved by the Synodal Liturgical Commission and by His Holiness Patriarch Alexy II of Moscow and All Rus on August 26, 2002, regulates the right to use both bells and semantrons in Orthodox ringing.

The National Museum of the Republic of Karelia displays two semantrons, which were made in 1706 and 1709.

This instrument has a long history. In the first centuries of Christianity in the Roman Empire, residents of cities and villages were summoned by alarm instruments — wooden or metal planks. In Russia, the semantron also predated the invention of bells. It notified residents of fires, enemy attacks, or other disasters. The semantron could also be used instead of a church bell: it summoned parishioners for matins, vespers, and feast rites.

During the reign of Peter the Great, semantrons appeared at shipyards and Petrovsky Plant. They replaced the huge bells, which had been removed and melted down into cannons. A semantron was used to signal the beginning and the end of the work.

The instrument was made in the form of a cast-iron board, which had the shape of a bell, with a relief image. There was a round hole in the upper part of the instrument — this hole was used to suspend it from a crossbar.

Semantrons were produced from rolled sheet metal: it is more homogeneous and dense compared to the cast bell. The sound was clear and long — it lasted for 1–2 minutes, while the ringing of good bells could be heard for 10–30 seconds, depending on the weight and the quality of the metal. Semantrons have a lower sound than bells. Striking a semantron, the player chooses the place of impact, thereby changing not the pitch, but the timbre. By striking different areas, one can play a simple melody.

According to experts, the Orthodox tradition of using wooden and metal semantrons is going to exist for a long time. The Statute of the Church Bell of the Russian Orthodox Church, which was approved by the Synodal Liturgical Commission and by His Holiness Patriarch Alexy II of Moscow and All Rus on August 26, 2002, regulates the right to use both bells and semantrons in Orthodox ringing.

The National Museum of the Republic of Karelia displays two semantrons, which were made in 1706 and 1709.