On June 27, 1709, the decisive battle of the Great Northern War took place, which put an end to the dominance of Sweden in Europe — the Battle of Poltava. Wishing to honor the “memory of glorious days”, Peter the Great ordered four “histories” or “tapestries of battles” — images of the main victories of the Russian army. Peter I chose the subjects for the tapestries himself: the Battle of Lesnaya, the naval Battle of Gangut and two episodes of the Battle of Poltava.

In 1717 Pierre-Denis Martin Jr. signed a contract to produce colored cartoons (sketches) to be hung as future wall carpets. This Parisian battle painter (circa 1663–1742) was considered the greatest master of his time.

Bearing in mind that the paintings were intended as a gift to Empress Catherine I, the master worked tirelessly in accordance with the strict canons of the battle genre of the 16th–18th centuries. He requested samples of flag emblems and battle diagrams be sent to him so he could convey in detail the beauty of the battles, the environment, the characters of the main participants. At the same time, he constantly demanded more money and suspended work until the next payments.

Additionally, according to the tradition of his time, Peter the Great commissioned French engravers to make copies of these cartoons. Nicolas de Larmessin and Charles Louis Simoneau worked on the “Battle of Poltava”; Larmessin also made “The Battle of Lesnaya”, and Simoneau — “The End of the Battle of Poltava”. The “Naval Battle” was engraved by Maurice Baquoy.

Work on this order — both the production of cartoons, weaving and engraving — progressed slowly and was completed only in 1725–1726, after the death of the emperor. However, he managed to evaluate the work of the French masters when he received Marten’s modellos (quarter-size copies of the future tapestry) and wood print boards for subsequent engravings.

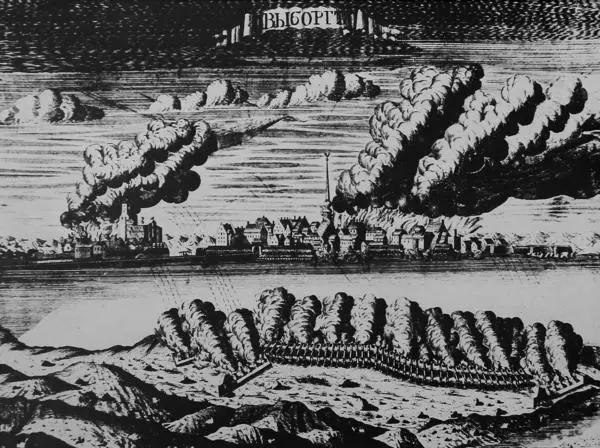

Thanks to the elongated format and the high horizon line, the artist was able to convey a deep perspective and fit many figures and details into the print. Emperor Peter I and King Charles XII are in the foreground.

These monumental tapestries did not interest the heirs of Peter I, and for about two decades they lay in the storerooms and lost their color. What became of them is unknown. Two cartoons dedicated to the Poltava victory and engravings have been preserved.

The sheets of the “Poltava

Battle” were particularly popular, even in the 19th century they could be found

in the shop of the Academy of Arts; today the prints from the copper boards of

Larmessin are included in the

collections of graphics of Russian museums.