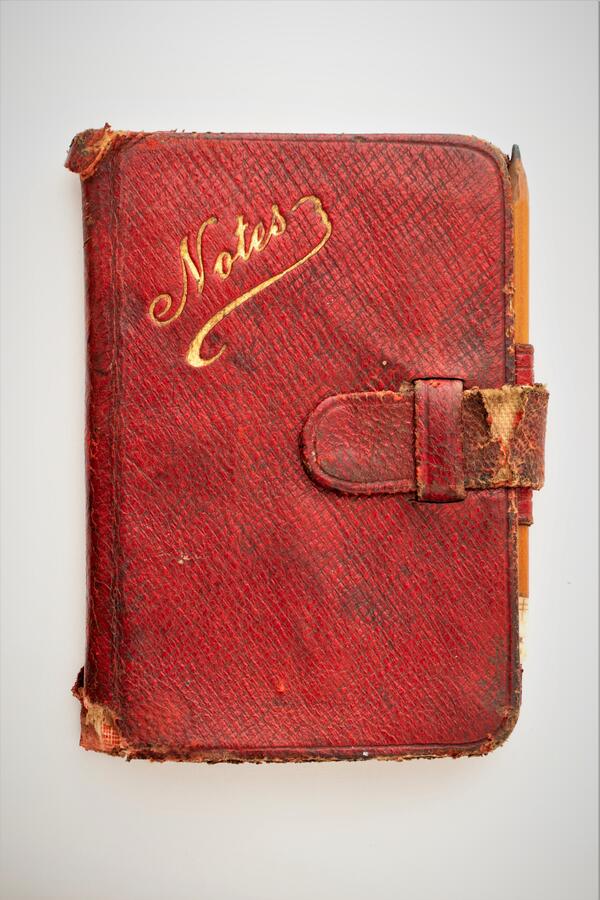

A ballroom book is kept in the exhibition of the department “History and Culture of the Sergiev Posad Region of the 20th century”. This is a miniature item in a hardcover made of burgundy leather with gold embossing and with an inscription in French “Notes” (notes). It is complemented by a small graphite pencil with a bone tip.

Such notebooks were among the mandatory attributes of noble balls in the 19th century, but they were used until the beginning of the 20th century. The ballroom book was also called a carnet de bal. It was used to record the names of the gentlemen with whom the lady promised to dance.

The first dance, as a rule, was a polonaise. It was usually danced by everyone present. Then the dance compositions went on almost uninterruptedly, and there were few who did not miss a single dance of the evening. While the invitations to small dances were always made at the ball itself, the quadrille, mazurka and cotillion were usually arranged in advance. Both the ladies and the gentlemen had their own records. Asking a successful lady for some big dance was almost hopeless. At the ball, if for some reason the lady turned down the gentleman, she had to skip this go: it wasn’t considered proper to accept an invitation of another man immediately after rejecting the first one.

Many ladies considered the ballroom book to be a list of their romantic triumphs, since the entries in it testified to the attention of men — and on the contrary, empty pages spoke of the unpopularity of the girl at the ball.

For convenience, ballroom books were made small, no bigger than a palm. Usually the carnet had a silver, bone or leather binding with gold embossing. The pages were paper or bone. Bone books served for a long time, as the text was erased from them with an elastic band or a damp cloth. The carnet was worn on a fan chain or fastened with a hook to the corsage of a ball gown.

Initially gaining popularity in Vienna in Austria, ballroom books made their way to other European countries, to Russia and the USA.

The book, which is presented in the exhibition, has 18 pages made of checked paper. Their edges are covered with gold paint. There are no records on the pages. This book supposedly belonged to a girl from a poor merchant class.

Such notebooks were among the mandatory attributes of noble balls in the 19th century, but they were used until the beginning of the 20th century. The ballroom book was also called a carnet de bal. It was used to record the names of the gentlemen with whom the lady promised to dance.

The first dance, as a rule, was a polonaise. It was usually danced by everyone present. Then the dance compositions went on almost uninterruptedly, and there were few who did not miss a single dance of the evening. While the invitations to small dances were always made at the ball itself, the quadrille, mazurka and cotillion were usually arranged in advance. Both the ladies and the gentlemen had their own records. Asking a successful lady for some big dance was almost hopeless. At the ball, if for some reason the lady turned down the gentleman, she had to skip this go: it wasn’t considered proper to accept an invitation of another man immediately after rejecting the first one.

Many ladies considered the ballroom book to be a list of their romantic triumphs, since the entries in it testified to the attention of men — and on the contrary, empty pages spoke of the unpopularity of the girl at the ball.

For convenience, ballroom books were made small, no bigger than a palm. Usually the carnet had a silver, bone or leather binding with gold embossing. The pages were paper or bone. Bone books served for a long time, as the text was erased from them with an elastic band or a damp cloth. The carnet was worn on a fan chain or fastened with a hook to the corsage of a ball gown.

Initially gaining popularity in Vienna in Austria, ballroom books made their way to other European countries, to Russia and the USA.

The book, which is presented in the exhibition, has 18 pages made of checked paper. Their edges are covered with gold paint. There are no records on the pages. This book supposedly belonged to a girl from a poor merchant class.