After the revolution of 1917, Ivan Silych Goryushkin-Sorokopudov was temporarily suspended from teaching. The Penza school was transformed into art and production workshops. Despite this setback, Goryushkin-Sorokopudov actively participated in the social and artistic life of the city. He joined the Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia and the Youth Organization of the Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia in Penza, where he demonstrated his works at various exhibitions organized by these associations.

Despite the interruption in his teaching career, Ivan Goryushkin-Sorokopudov devoted nearly half a century to education. During the Great Patriotic War, he was appointed head of the art school and the local art gallery. He supported his students during the difficult years of scarcity, finding ways for them to earn money and even providing them with food. His students fondly recalled that “there was nothing tastier in the world than the sorokopudovka potato.”

The students frequently visited the artist at his home in the village of Ivanovka, where the elderly master generously shared his experience with them. The final years of Ivan Silych Goryushkin-Sorokopudov’s life were filled with sadness as he lived alone in Ivanovka. He passed away on the night of December 31, 1954.

The artist’s life was marked by a profound devotion to art and a love for his craft, which required not only talent but also immense dedication and hard work. He produced a significant body of paintings and graphic works while mentoring a remarkable group of students. Among his many students were the Armenian painter and People’s Artist of the Armenian SSR Gabriel Mikayeli Gyurjyan, the Soviet Kazakh and Uzbek artist Ural Tansykbayevich Tansykbayev, and the Belarusian artist Valentin Viktorovich Volkov.

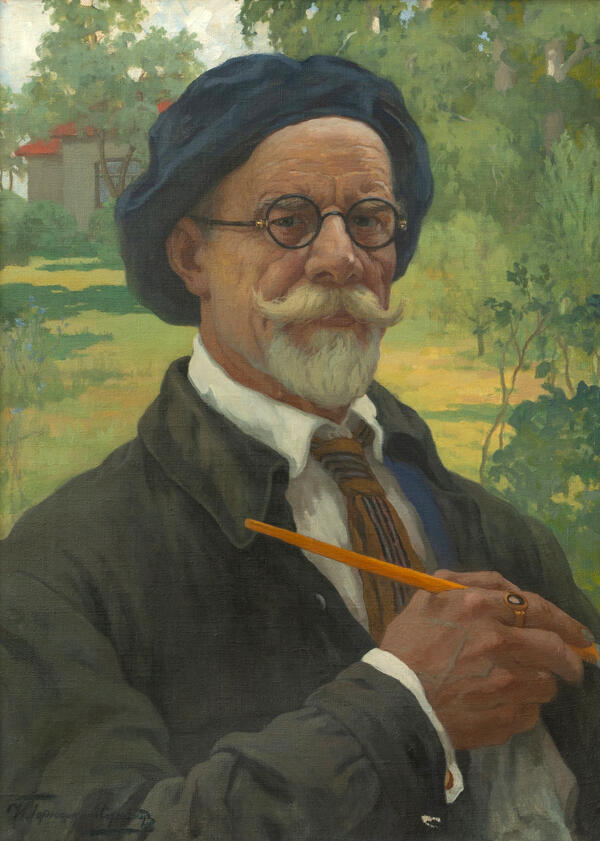

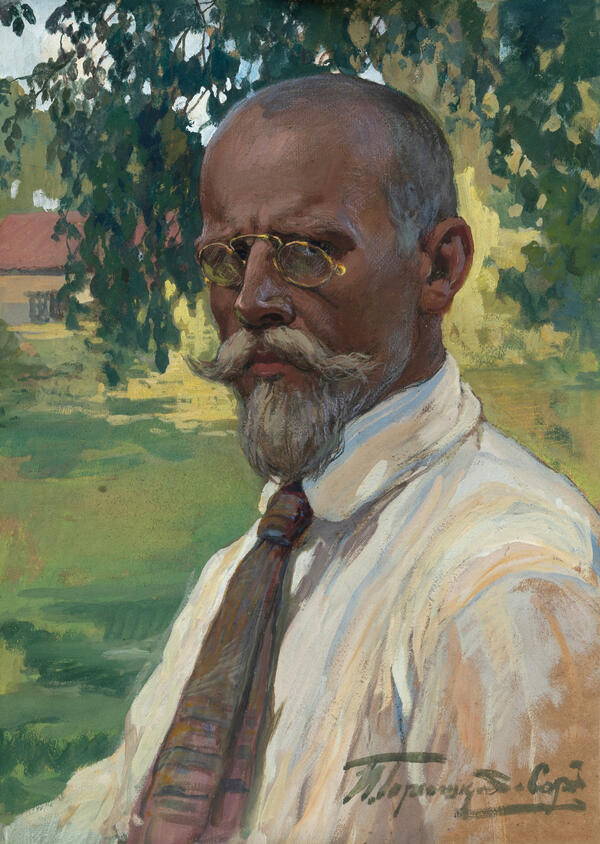

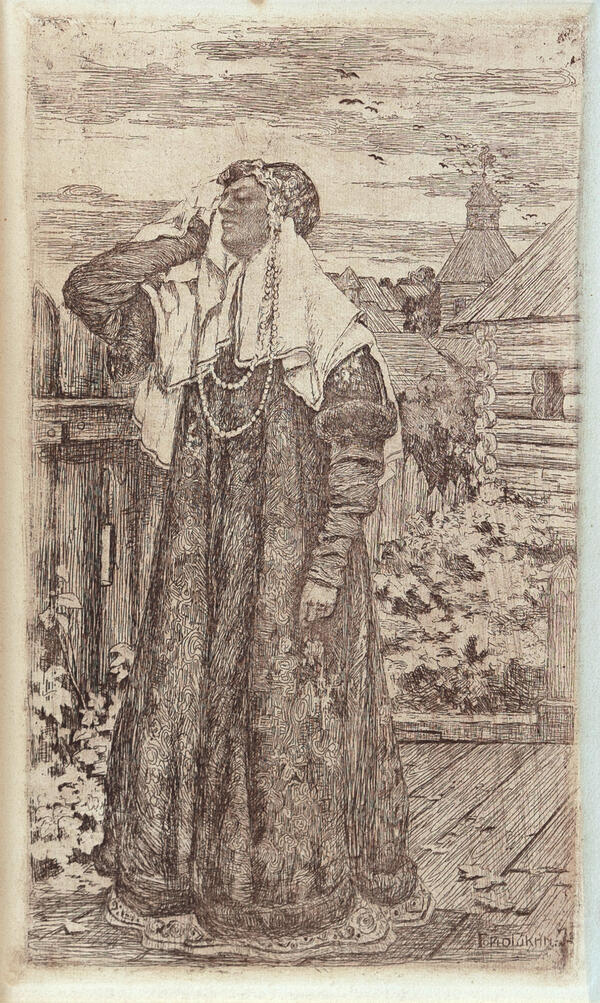

Ivan Goryushkin-Sorokopudov completed his self-portrait in the etching technique around the 1930s or 1940s. In this head-and-shoulders portrait from the museum collection, the artist is depicted with a pointed beard and upturned mustache. His inquisitive gaze is behind a pince-nez, and a smoking pipe rests between his teeth. The artist’s face is turned three-quarters, and it is likely that he supplemented the etching technique with drypoint, a traditional method used by graphic artists.