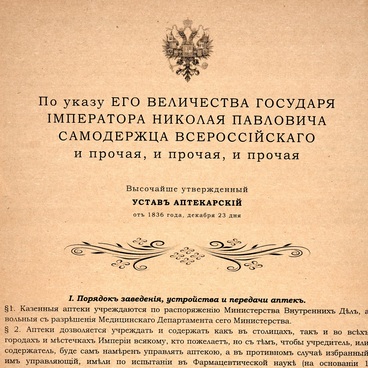

All pharmacies in The Russian Empire were controlled by the Medical Administration, which was part of the Department of Internal Affairs. Pharmacists wrote down every operation in a register, and there was a special document for each. All pharmacies had to keep a Formulary, a Book of sales of non-prescription drugs, a Book of poisons, and a Laboratory book, where all pharmaceuticals that were made for open sale were recorded. The pharmacy staff used special publications: a pharmacopoeia, which indicated the requirements for medicines, a list of practicing doctors, as well as a Pharmacy fee guide.

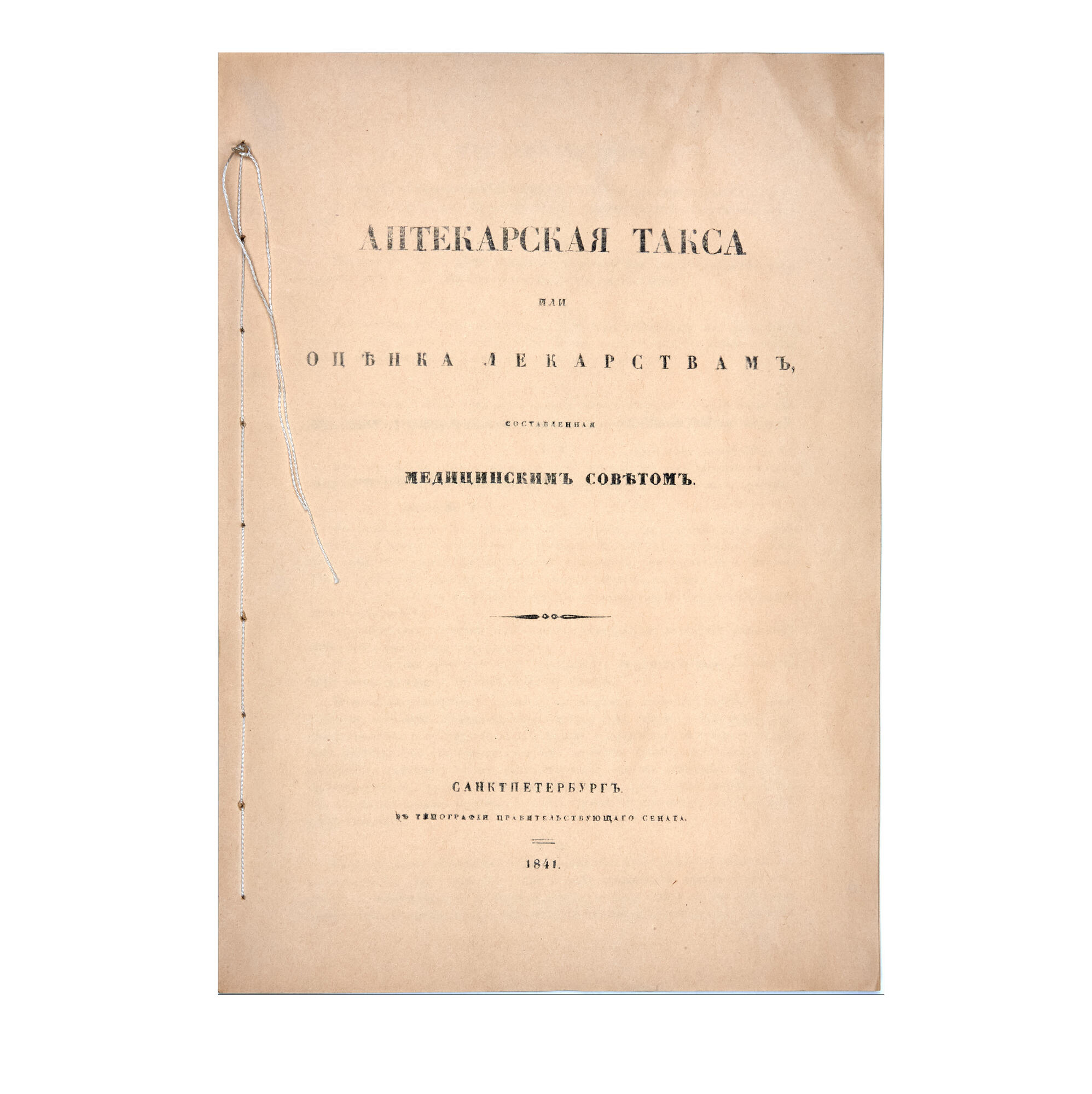

The Pharmacy fee guide was an official document that contained prices for medicines, containers, and the ‘manner of drug preparation’. The fee schedule was made up by the owners of large metropolitan pharmacies and was printed with the permission of the Medical Administration of the Russian Empire. The document passed the necessary certification, had the status of a legislative one, and was valid throughout the country.

The first Pharmacy fee guide in The Russian Empire was published on September 20, 1798, under the title ‘Prices of medicines, including: Pharmaceutical Charter. The Charter for midwives. The Charter on due pay for medical officers”. Compliance with the document was stipulated in the 12th paragraph of the Charter, which was valid until the beginning of the 20th century: “The pharmacist must charge the price for the dispensed medicines indicated in the published fee guide. When the price of a certain medicine rises or decreases in the future, then the State Medical Board will inform the public of the fact.”

The prices set in the document did not suit everyone. Anton Chekhov, who was also a practicing doctor, wrote in his humorous treatise “The Pharmacy fee guide, or Help me! I am being robbed!”: “The Pharmacy fee guide has a peculiarity: it recognizes the rules, but knows no exceptions. Its motto is " Сharge for everything without exception’. It charges for the preparation of the medicine, for mixing it, for stirring, saturating, dividing into fractions, for the wrapper, signature, label, seal, dishes, box, paper, binding thread, and so on.’

Despite the restrictions, the prices of pharmaceuticals in private pharmacies — and they made up the majority at that time — were 1.5–2 times higher than in district pharmacies of hospitals. The average prescription cost about 8 kopecks — one could buy a bottle of milk or half a kilo of wheat flour for this money.

The exhibition presents a mock edition of ‘Pharmacy fee or medicine guide, compiled by the medical council’ in 1841.