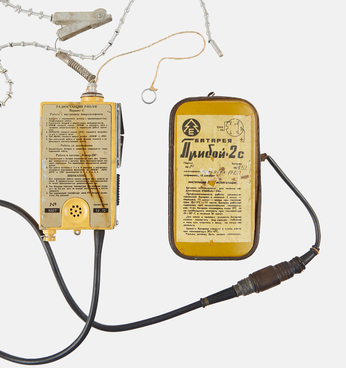

The explosion-proof telephone Tasha-2 comes from a series that was used in mining. Production started in the late 1960s at the Perm Telephone Plant. The devices were used at explosive enterprises of Group I (coal industry) and Group II (chemical plants, refineries, and oil and gas transportation companies).

Firedamp remained one of the biggest problems in underground coal mining throughout the history of the industry. Forming a mixture with oxygen, methane often exploded, and posed significant hazards to miners. Coal dust was also explosive. The very first method of detecting dangerous gasses was to bring a canary in a cage along into the mine. If the bird died it meant the level of firedamp and carbon monoxide in the mine was dangerous.

During early capitalism, mine owners ignored the harsh working conditions in the industry. In many mines temperatures rose to 34°C. Under such conditions, a miner could work for about 20 minutes. Mine owners realized that miners’ inability to work for a long time in the heat had a direct effect on the income of the enterprise. This prompted them to start investing in ventilation systems. When the electric motor was invented and came into use, the electrification of mining began. Today, the lifting mechanisms of mine cages, pumps, and fans are driven by electric motors. Using electric motors, rigs drill holes and fill them with explosives, which are set off with an electric fuse. Electric light became a safe alternative to the old ways of lighting. Electrification led to technological advance and transformed mining. The application of electricity in mines made it possible to install telephones, like those that are on display in the permanent exhibition of the museum.

To protect the internal parts from damage, coal dust and gas, the phone has a reinforced sealed housing. In addition, it has a loud sound, so that the call can be heard in the noisy mining environment. The device normally works with any conventional telephone system that uses pulse dialing. In the 1990s, due to the difficult situation in the mining industry, most of these devices were stolen and sold for scrap. Then they were replaced by another model with a durable plastic housing, and the Tasha-2 is now seldom used by factories.

In 2015, the exhibit was donated to the Rusanov

House Museum by Natalia Shmatova, editor-in-chief of “The Russian Bulletin of

Svalbard”.