The establishment of Soviet power in Taimyr was a long and complicated process that was only completed by the late 1930s: in many ways, the new ideology ran counter to the age-old traditions of the nomadic peoples.

The process began in January 1920. First of all, the new authorities decided to deal with establishing the political order of the indigenous minorities, eliminating illiteracy, and developing corporate trade. As a result, Red Chums began to appear in Taimyr. The “hearth of new life” was housed in a balok (mobile hut) — the traditional dwelling of the tundra people; the workers of the Red Chums combined the positions of a doctor, teacher, librarian, and educator.

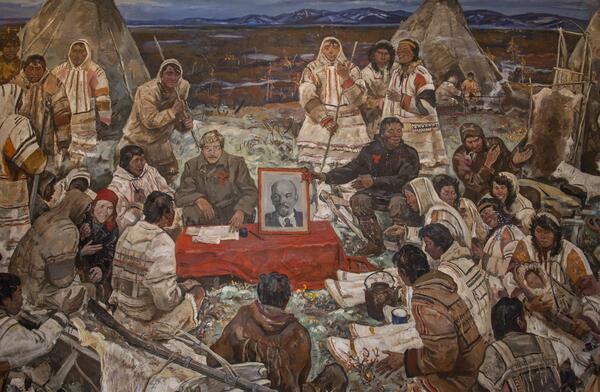

The painting depicts a meeting at a Nganasan nomad camp dedicated to political education. Amalia Mikhailovna Khazanovich, a Russian woman in a red kerchief, stands out among the other figures.

The 24-year-old Amalia Khazanovich arrived at Taimyr in 1936 as a member of the Komsomol delegation of 100 young people who were sent to the Arctic for education purposes. Before that, she had worked in the Urals as a secretary of a village Soviet executive committee and the head of a village reading room, in Moscow — as an employee of the “Moscow collective farm newspaper” and at the tool-making plant. All these skills, both organizational and locksmith ones, came in handy in the tundra.

As the head of the Red Chum of the Hatanga cultural center of Glavsevmorput Khazanovich from autumn of 1936 till April 1937 lived among Dolgans, provided medical help, taught them hygienic and literacy skills, and read and discussed the USSR Constitution with them. She worked in the village of Isayevsky, halfway between Khatanga and Volochanka.

Having met the ethnographer Andrey Andreevich Popov, who visited the nomad camp, and having heard his stories about the Nganasans, Amalia Mikhailovna asked to be sent to this even less enlightened people. All in all, she worked in the tundra for more than 15 years, roaming together with the people under her care. Her Red Chum traveled 2,000 kilometers across the tundra.

The efforts of Amalia Khazanovich and her high authority among the locals resulted in the establishment of a hunting and fishing farm “Leninsky Put” in 1938. Khazanovich’s detailed diary is documented in her book “My Friends, Nganasans: From Taimyr Diaries”.

After completing her mission in the tundra, Amalia Mikhailovna worked in cultural, meteorological, and geological fields. Amalia Khazanovich’s ashes were transported to the tundra according to her will. There, in the village of Novaya (Khatanga), an obelisk in honor of the famous teacher was erected.

The process began in January 1920. First of all, the new authorities decided to deal with establishing the political order of the indigenous minorities, eliminating illiteracy, and developing corporate trade. As a result, Red Chums began to appear in Taimyr. The “hearth of new life” was housed in a balok (mobile hut) — the traditional dwelling of the tundra people; the workers of the Red Chums combined the positions of a doctor, teacher, librarian, and educator.

The painting depicts a meeting at a Nganasan nomad camp dedicated to political education. Amalia Mikhailovna Khazanovich, a Russian woman in a red kerchief, stands out among the other figures.

The 24-year-old Amalia Khazanovich arrived at Taimyr in 1936 as a member of the Komsomol delegation of 100 young people who were sent to the Arctic for education purposes. Before that, she had worked in the Urals as a secretary of a village Soviet executive committee and the head of a village reading room, in Moscow — as an employee of the “Moscow collective farm newspaper” and at the tool-making plant. All these skills, both organizational and locksmith ones, came in handy in the tundra.

As the head of the Red Chum of the Hatanga cultural center of Glavsevmorput Khazanovich from autumn of 1936 till April 1937 lived among Dolgans, provided medical help, taught them hygienic and literacy skills, and read and discussed the USSR Constitution with them. She worked in the village of Isayevsky, halfway between Khatanga and Volochanka.

Having met the ethnographer Andrey Andreevich Popov, who visited the nomad camp, and having heard his stories about the Nganasans, Amalia Mikhailovna asked to be sent to this even less enlightened people. All in all, she worked in the tundra for more than 15 years, roaming together with the people under her care. Her Red Chum traveled 2,000 kilometers across the tundra.

The efforts of Amalia Khazanovich and her high authority among the locals resulted in the establishment of a hunting and fishing farm “Leninsky Put” in 1938. Khazanovich’s detailed diary is documented in her book “My Friends, Nganasans: From Taimyr Diaries”.

After completing her mission in the tundra, Amalia Mikhailovna worked in cultural, meteorological, and geological fields. Amalia Khazanovich’s ashes were transported to the tundra according to her will. There, in the village of Novaya (Khatanga), an obelisk in honor of the famous teacher was erected.