In 1901, Guillon Kemmler, an employee of the French film studio and equipment manufacturer “Pathe”, came up with an idea on how to improve the gramophone — a mechanical device for reproducing sound from records. He reduced the horn for transmitting sound and embedded it into the case. The new sound transmitting device turned out to be compact and portable, it was named after the company — a pathephone (gramophone).

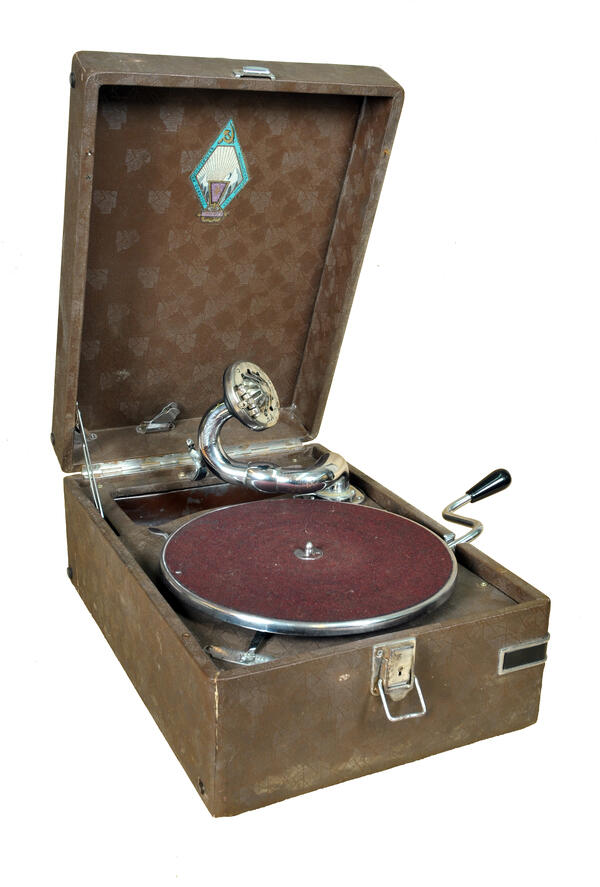

The pathephone was shaped like a briefcase. Pathephones were produced in different cases — from cheap leatherette to gift lacquer. Inside the case, there was a mechanical device for playing gramophone records. It consisted of a spring motor with a round disk, a pickup — a metal needle and a membrane, as well as a sound amplifier hidden inside the case.

The engine spring was wound up using a removable handle, which was inserted into the hole on the right side of the device. In the trail position, the handle was fixed on the inside of the gramophone cover. In some models, there were also mounts for plates located there.

One winding of the spring was enough to play one or two sides of a record, each three minutes long. The pathephones were quite loud, but the sound quality was low and depended on the needle deterioration and the number of times the record had been played.

The PT-3 pathephones, a Soviet replica from the British His Master’s Voice, were produced from 1933 to 1939 by the Vladimir gramzavod (Vladimir Gramophone Producing Plant). In 1939, by order of the People’s Commissar of Ammunition, it was renamed the State Union Plant No. 260, and by 1940 it began to produce fuses for aerial bombs and shells. In 1941, the company was evacuated to Molotov (Perm). A year later, the factory returned to Vladimir, but the phonograph production remained in Molotov. Since 1946, it has been called the Molotov Gramophone Factory.

The Kalashnikovs purchased a Perm-made pathephone, most likely after 1952, when they received a separate two-room apartment. The museum’s funds house the photographs of an old apartment from the family archive that show the silhouette of a pathephone briefcase in the background.

The pathephone was shaped like a briefcase. Pathephones were produced in different cases — from cheap leatherette to gift lacquer. Inside the case, there was a mechanical device for playing gramophone records. It consisted of a spring motor with a round disk, a pickup — a metal needle and a membrane, as well as a sound amplifier hidden inside the case.

The engine spring was wound up using a removable handle, which was inserted into the hole on the right side of the device. In the trail position, the handle was fixed on the inside of the gramophone cover. In some models, there were also mounts for plates located there.

One winding of the spring was enough to play one or two sides of a record, each three minutes long. The pathephones were quite loud, but the sound quality was low and depended on the needle deterioration and the number of times the record had been played.

The PT-3 pathephones, a Soviet replica from the British His Master’s Voice, were produced from 1933 to 1939 by the Vladimir gramzavod (Vladimir Gramophone Producing Plant). In 1939, by order of the People’s Commissar of Ammunition, it was renamed the State Union Plant No. 260, and by 1940 it began to produce fuses for aerial bombs and shells. In 1941, the company was evacuated to Molotov (Perm). A year later, the factory returned to Vladimir, but the phonograph production remained in Molotov. Since 1946, it has been called the Molotov Gramophone Factory.

The Kalashnikovs purchased a Perm-made pathephone, most likely after 1952, when they received a separate two-room apartment. The museum’s funds house the photographs of an old apartment from the family archive that show the silhouette of a pathephone briefcase in the background.