One of the most significant sources of replenishment of the Royal Treasury was the collection of yasak, a tribute paid off in furs, the main wealth of the annexed Siberian lands. Yasak was collected from every native resident of the region in recognition of the power of the Russian Tsar. But people who had to pay yasak did not always pay it on a voluntary basis, so they were sworn in, the so-called shert. They swore in on religious beliefs.

The amount of the fur tax was agreed upon by the natives themselves. There was also the practice of giving gifts – all sorts of beads, metal products, fabrics, bread instead of yasak. It was like barter. However, soon the Central government began to demand a census of all people who had to pay yasak and a strictly fixed size of yasak. Thus, the collection of yasak gradually became a kind of state tax.

In their relations with the native population of Siberia, the Moscow governors sought to find support in the local patriarchal nobility. Voivodes and clerks wishing to simplify yasak calculations preferred to deal only with aboriginal leaders. For this reason, patrimonial and tribal leaders were granted various privileges and officially declared ‘lords’, ‘best people’.

At the same time, to become a citizen a person should swear in to the local nobility, it was also given ‘a word of nobility’. Both were similar to the conclusion of a contract, although unequal, that fixed mutual obligations.

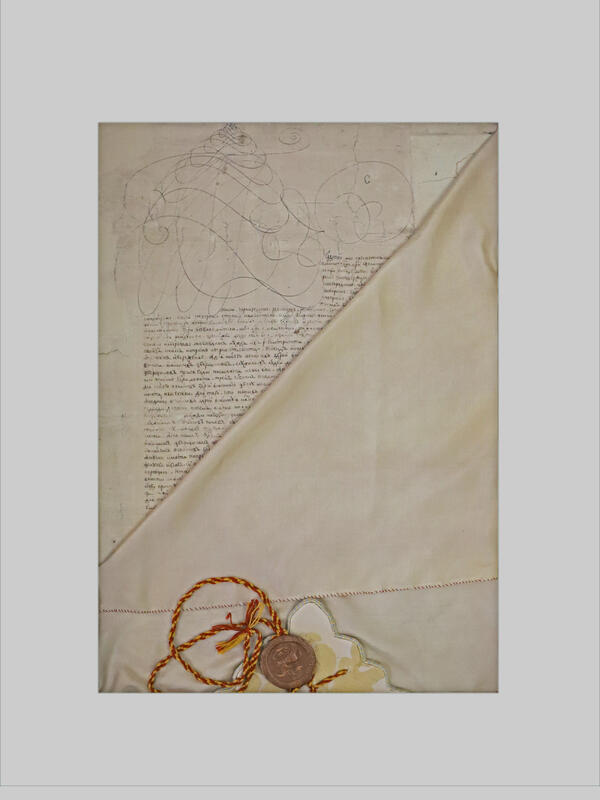

An example of such contractual relationship was the ‘Patent of nobility granted by tsars Ioann and Peter Alekseevich to Yuzor Raidukov, Lord of the city of Berezov, on the management of the Kazymsky volost and on the procedure for collecting yasak from Ostyaks’, compiled on December 28, 1692. According to such documents, the aboriginal population had to pay yasak and remain loyal to the tsar. In turn, the Russian sovereign granted them the right to live and operate in the areas of their native habitat, promised to keep them ‘in his Royal mercy’ and ‘protect them firmly.’

The amount of the fur tax was agreed upon by the natives themselves. There was also the practice of giving gifts – all sorts of beads, metal products, fabrics, bread instead of yasak. It was like barter. However, soon the Central government began to demand a census of all people who had to pay yasak and a strictly fixed size of yasak. Thus, the collection of yasak gradually became a kind of state tax.

In their relations with the native population of Siberia, the Moscow governors sought to find support in the local patriarchal nobility. Voivodes and clerks wishing to simplify yasak calculations preferred to deal only with aboriginal leaders. For this reason, patrimonial and tribal leaders were granted various privileges and officially declared ‘lords’, ‘best people’.

At the same time, to become a citizen a person should swear in to the local nobility, it was also given ‘a word of nobility’. Both were similar to the conclusion of a contract, although unequal, that fixed mutual obligations.

An example of such contractual relationship was the ‘Patent of nobility granted by tsars Ioann and Peter Alekseevich to Yuzor Raidukov, Lord of the city of Berezov, on the management of the Kazymsky volost and on the procedure for collecting yasak from Ostyaks’, compiled on December 28, 1692. According to such documents, the aboriginal population had to pay yasak and remain loyal to the tsar. In turn, the Russian sovereign granted them the right to live and operate in the areas of their native habitat, promised to keep them ‘in his Royal mercy’ and ‘protect them firmly.’