A rushlight holder (svetets) is an iron forged stand designed to keep a burning rushlight. For centuries, it was the only source of artificial light that peasants used at home. Rushlight holders were made for local use and were not sold at major markets. The stands were used both in peasants’ huts and churches.

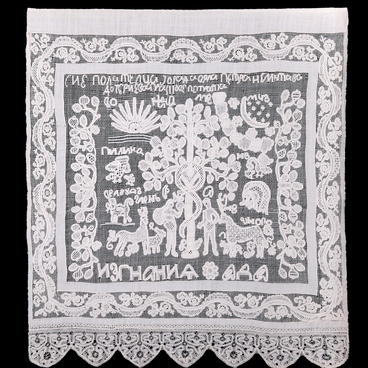

The rushlight holder from the collection of folk art in the Russian Museum consists of a massive ring with strips riveted to it. There is a long rod fixed at the intersection of these strips. The rushlight holder was put into a basin of water. On top of the rod are three clamps — holders for a torch in the form of a silhouette of a flower — a lily. Two of them sit on smoothly curved “stems” and symmetrically flank the rod. The overall design is enriched with forged scrolls twisting in spirals below each of the three flowers. In the middle are two different C-shaped details that form a “dynka”. In Old Russian stone and wooden architecture, as well as in folk art from the 15th to the 18th centuries, a “dynka” was a decorative element of pillars, columns, door portals and window casings in the form of various thickenings, that were ball-shaped or resembled a melon.

The presented rushlight holder came to the Russian Museum from the State Hermitage in 1938. Previously, it was in the museum of the Central School of Technical Drawing of Baron A.L. Stieglitz, for whose collection it was purchased in 1913 from the antique shop of Briana Milman. The shop was in on Voznesensky Prospekt in St. Petersburg. It is known that Lyubov Dmitrievna Blok (the wife of the poet Alexander Blok) bought chairs from Briana Milman for their apartment on Galernaya Street. After the revolution of 1917, the antique shop was closed, and the goods were nationalized.

The rushlight holder is a piece of high artistic value. The craftsman managed to create the image of a magical flower stretching towards the sun. As Natalya Sergeevna Grigoryeva, a well-known researcher of folk art, wrote, “the ornament grows and reaches a magnificent development in the upper part, turning into the main decorative motif, however, not without practical meaning.” The roughness, strength and beauty of elaborate scrolls arrest the viewer’s attention; they form an intricate pattern, reminiscent of calligraphic pen strokes.

In such works, the harmony of the artistic image was combined with the magnificent skill of blacksmiths who used various techniques.

The rushlight holder from the collection of folk art in the Russian Museum consists of a massive ring with strips riveted to it. There is a long rod fixed at the intersection of these strips. The rushlight holder was put into a basin of water. On top of the rod are three clamps — holders for a torch in the form of a silhouette of a flower — a lily. Two of them sit on smoothly curved “stems” and symmetrically flank the rod. The overall design is enriched with forged scrolls twisting in spirals below each of the three flowers. In the middle are two different C-shaped details that form a “dynka”. In Old Russian stone and wooden architecture, as well as in folk art from the 15th to the 18th centuries, a “dynka” was a decorative element of pillars, columns, door portals and window casings in the form of various thickenings, that were ball-shaped or resembled a melon.

The presented rushlight holder came to the Russian Museum from the State Hermitage in 1938. Previously, it was in the museum of the Central School of Technical Drawing of Baron A.L. Stieglitz, for whose collection it was purchased in 1913 from the antique shop of Briana Milman. The shop was in on Voznesensky Prospekt in St. Petersburg. It is known that Lyubov Dmitrievna Blok (the wife of the poet Alexander Blok) bought chairs from Briana Milman for their apartment on Galernaya Street. After the revolution of 1917, the antique shop was closed, and the goods were nationalized.

The rushlight holder is a piece of high artistic value. The craftsman managed to create the image of a magical flower stretching towards the sun. As Natalya Sergeevna Grigoryeva, a well-known researcher of folk art, wrote, “the ornament grows and reaches a magnificent development in the upper part, turning into the main decorative motif, however, not without practical meaning.” The roughness, strength and beauty of elaborate scrolls arrest the viewer’s attention; they form an intricate pattern, reminiscent of calligraphic pen strokes.

In such works, the harmony of the artistic image was combined with the magnificent skill of blacksmiths who used various techniques.