Nikolai Semyonovich Golovanov carried a penchant for spirituality, religion and old Russian painting throughout his entire life. The conductor amassed an impressive private collection of ancient Russian art, and his selection of icons was considered one of the best among his contemporaries.

Golovanov’s collection of icons contained both modern replicas and rare old images dating back to the 15th century. There were various ways how they ended up in the conductor’s possession. Golovanov acquired some of the works through intermediaries, while others were saved from churches shut down by the Soviet authorities. As a rule, the works were placed in the bedroom and could be seen only by family members. There are two reasons as to why that magnificent collection was concealed to avoid unwanted attention, the first being that faith is a deeply personal experience. And the second was that, given the state of Soviet reality, the propaganda of atheism, and the general cultural situation, it was impossible and dangerous for Nikolai Golovanov to be open about his religious beliefs.

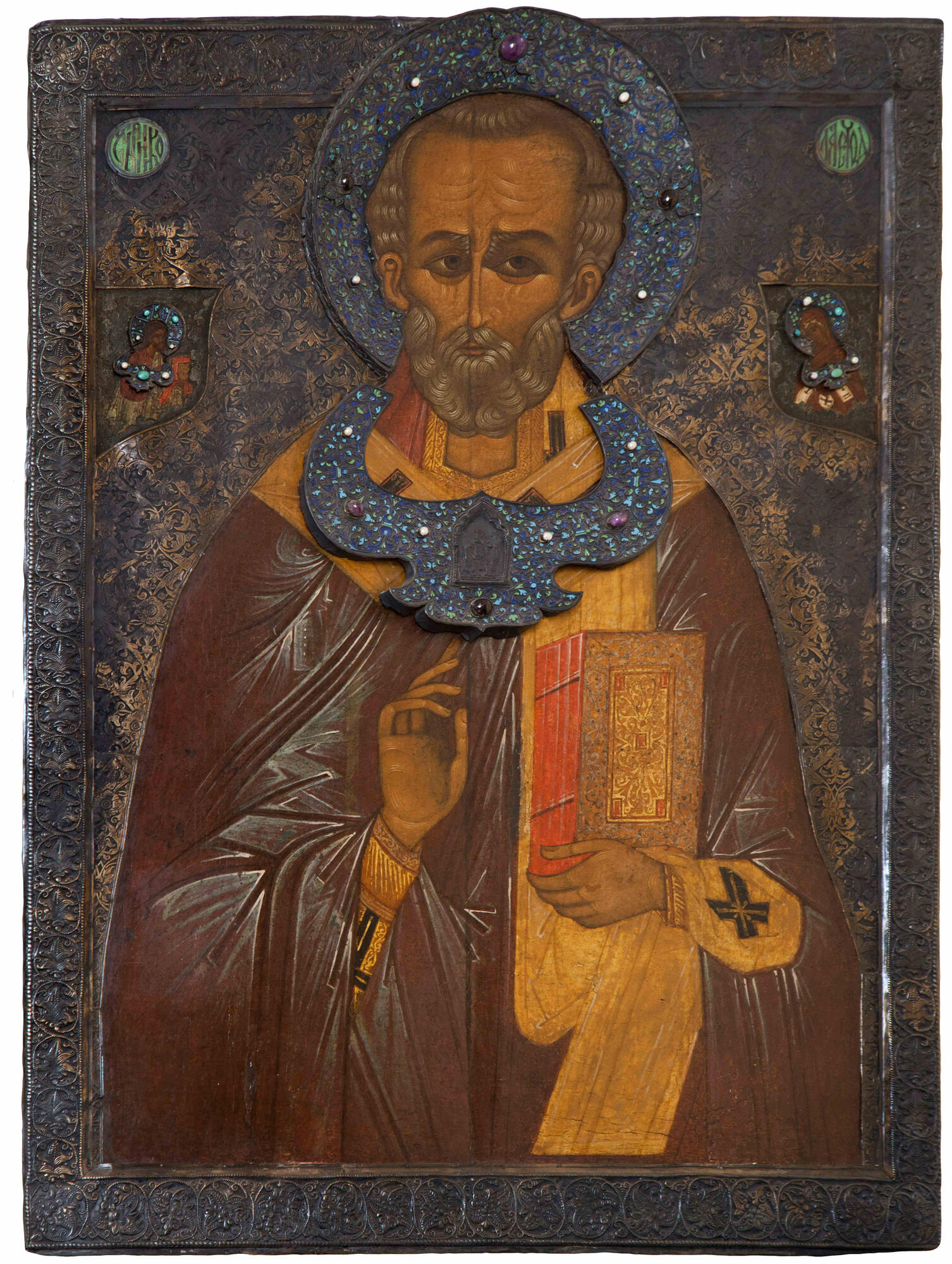

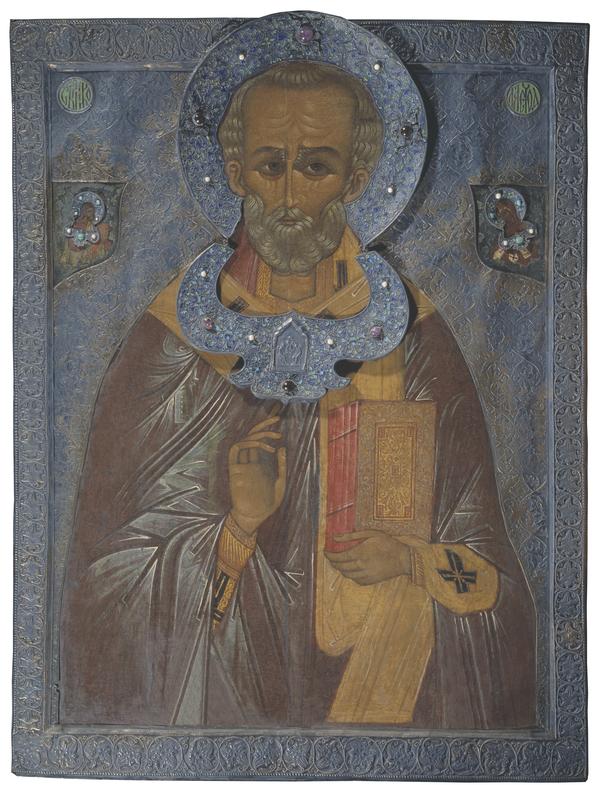

Currently, the collection includes about 28 icons. After the conductor’s death, a significant part of the works of old Russian art — over 60 pieces — were transferred to the Tretyakov Gallery, while the whereabouts of another 58 icons remain unknown. However, even the small number of images that remained in the apartment museum offers a glimpse of the original collection, which Nikolai Golovanov cherished not only for the expressiveness and spirituality of the images but also for the various techniques used for their creation and the originality of the artistic concept. One of the most outstanding exhibits is the image that dates back to the 17th century and depicts one of the most revered saints in Eastern Orthodoxy, Nicholas the Wonderworker, who was the patron saint of Nikolai Golovanov. The icon has survived intact to this day, and its exquisite beauty is still remarkable: the impressive dimensions of the wooden painting surface; the strict image of the saint; the fine manner of painting, with a clear pattern of whitewash, accentuating folds in the clothes; the wrought metal revetment, halo and tsatas, decorated with filigree with enamels and encrusted with gemstones — all that creates a deeply spiritual image.

Golovanov’s collection of icons contained both modern replicas and rare old images dating back to the 15th century. There were various ways how they ended up in the conductor’s possession. Golovanov acquired some of the works through intermediaries, while others were saved from churches shut down by the Soviet authorities. As a rule, the works were placed in the bedroom and could be seen only by family members. There are two reasons as to why that magnificent collection was concealed to avoid unwanted attention, the first being that faith is a deeply personal experience. And the second was that, given the state of Soviet reality, the propaganda of atheism, and the general cultural situation, it was impossible and dangerous for Nikolai Golovanov to be open about his religious beliefs.

Currently, the collection includes about 28 icons. After the conductor’s death, a significant part of the works of old Russian art — over 60 pieces — were transferred to the Tretyakov Gallery, while the whereabouts of another 58 icons remain unknown. However, even the small number of images that remained in the apartment museum offers a glimpse of the original collection, which Nikolai Golovanov cherished not only for the expressiveness and spirituality of the images but also for the various techniques used for their creation and the originality of the artistic concept. One of the most outstanding exhibits is the image that dates back to the 17th century and depicts one of the most revered saints in Eastern Orthodoxy, Nicholas the Wonderworker, who was the patron saint of Nikolai Golovanov. The icon has survived intact to this day, and its exquisite beauty is still remarkable: the impressive dimensions of the wooden painting surface; the strict image of the saint; the fine manner of painting, with a clear pattern of whitewash, accentuating folds in the clothes; the wrought metal revetment, halo and tsatas, decorated with filigree with enamels and encrusted with gemstones — all that creates a deeply spiritual image.