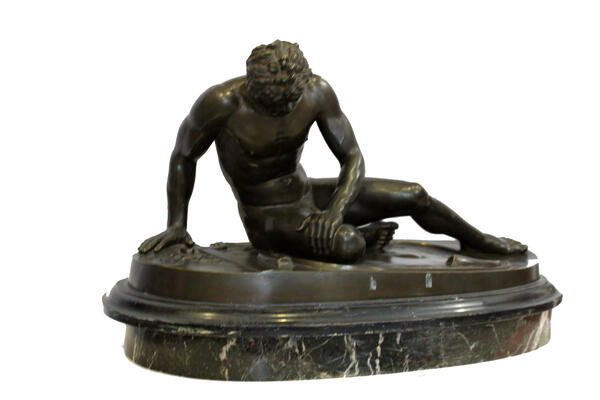

The sculpture Dying Gaul was brought to the Syzran Museum of Local History and Lore in 1925 from the estate of the Orlov-Davydovs in the village of Usolye. The exact same sculpture, except in marble, can be found in the State Hermitage Museum, and stone copies are exhibited in the Peterhof museum preserve and in the Tsarskoye Selo museum preserve.

The Dying Gaul is also known as the Death of the Galatian or the Dying Gladiator. The bronze sculpture is a smaller copy of the marble copy of the Pergamon original (presumably bronze), preserved in the Capitoline Museums in Rome, which was made on the order of King Attalus I to commemorate his victory over the Celts-Galatians. The original, which was created by the court sculptor Epigon, may well have been part of a large sculptural ensemble for the square of the sanctuary of Athena in Pergamum.

The statue, like the three-sided ancient Greek relief ‘Throne of Ludovisi, ’ was discovered during the construction of a villa in Rome. Prior to being acquired by Pope Clement XII, it was kept in the Palazzo Ludovisi on Pincho. During the Napoleonic Wars, the French looted The Dying Gaul from Italy and exhibited it in the Louvre for several years. Lord George Gordon Byron saw the statue in the Capitol Museum and sang praises to it in Child Harold’s Pilgrimage: thanks to this poem, the statue soon became very famous all across Europe.

The Gaul warrior is shown with the characteristic thick head of hair and a mustache as was the custom among the Celts. He’s lying on an oval shield, completely naked, with only a torque around his neck, this being a kind of a Celtic necklace. The Celts considered torques as a talisman and insignia, so they did not go into battle without one.

In terms of detail and drama, the sculpture was clearly made at the peak of ancient art. The Gaul is depicted in the last minutes of his life, his face is contorted in pain as he is dying from a fatal wound. The bleeding hole from the sword can be seen on the chest on the right. There is a broken sword with a belt and a horn lying under his right hand. The idea was for the statute to be a reminder of the defeat of the Celts and the power of the victors while also paying respect to the gallantry of the Gauls as worthy enemies.

The Dying Gaul is also known as the Death of the Galatian or the Dying Gladiator. The bronze sculpture is a smaller copy of the marble copy of the Pergamon original (presumably bronze), preserved in the Capitoline Museums in Rome, which was made on the order of King Attalus I to commemorate his victory over the Celts-Galatians. The original, which was created by the court sculptor Epigon, may well have been part of a large sculptural ensemble for the square of the sanctuary of Athena in Pergamum.

The statue, like the three-sided ancient Greek relief ‘Throne of Ludovisi, ’ was discovered during the construction of a villa in Rome. Prior to being acquired by Pope Clement XII, it was kept in the Palazzo Ludovisi on Pincho. During the Napoleonic Wars, the French looted The Dying Gaul from Italy and exhibited it in the Louvre for several years. Lord George Gordon Byron saw the statue in the Capitol Museum and sang praises to it in Child Harold’s Pilgrimage: thanks to this poem, the statue soon became very famous all across Europe.

The Gaul warrior is shown with the characteristic thick head of hair and a mustache as was the custom among the Celts. He’s lying on an oval shield, completely naked, with only a torque around his neck, this being a kind of a Celtic necklace. The Celts considered torques as a talisman and insignia, so they did not go into battle without one.

In terms of detail and drama, the sculpture was clearly made at the peak of ancient art. The Gaul is depicted in the last minutes of his life, his face is contorted in pain as he is dying from a fatal wound. The bleeding hole from the sword can be seen on the chest on the right. There is a broken sword with a belt and a horn lying under his right hand. The idea was for the statute to be a reminder of the defeat of the Celts and the power of the victors while also paying respect to the gallantry of the Gauls as worthy enemies.