Bone carving is an ancient craft practiced in the Russian North since ancient times.

The Kholmogory school of bone carving has been known since the 17th century. Having absorbed the Northern Russian traditions, as well as the techniques of German, Dutch masters and traditions of the indigenous peoples of the North, the special Kholmogory style finally developed only by the 18th century. It is mainly characterized by openwork designs and finest openwork carving. Fabulous floral ornaments and elegant rocailles are combined with relief images inspired by various plots and decorated with color-filled engraving.

Some of the oldest products are prayer beads, mouthpieces, and combs with the finest teeth. All kinds of boxes and caskets modeled after Kholmogory chests, as well as snuffboxes, photo frames, icons, miniatures and portraits were also popular. Later, the artisans began to make glasses, vases, chess and checkers sets, interior cladding, copies of famous sculptures and decorative compositions on a variety of topics.

The best Kholmogory carvers were invited to work in the Armory Chamber to create items for the royal court. Peter I patronized the masters, providing them with samples of Western bone-cutting art, and Catherine I used Kholmogory carved caskets for personal belongings. Bone products were presented as memorable gifts to important persons, and monasteries and churches commissioned the masters to make various items. Ivan Krusenstern even brought the decorative vases created by the master Nikolay Vereshchagin, presently housed in the Hermitage Museum, on the first Russian circumnavigation of the Earth: those were to be presented to the Japanese emperor, but the embassy refused to accept them.

Many villages in the vicinity of Kholmogory were engaged in this craft. For example, the most significant Russian sculptor of the 18th century, Fedot Shubin, came from a family of bone-cutters from the village of Tyuchkovskaya.

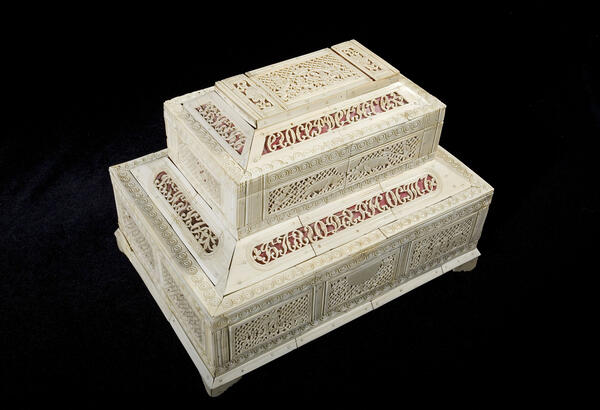

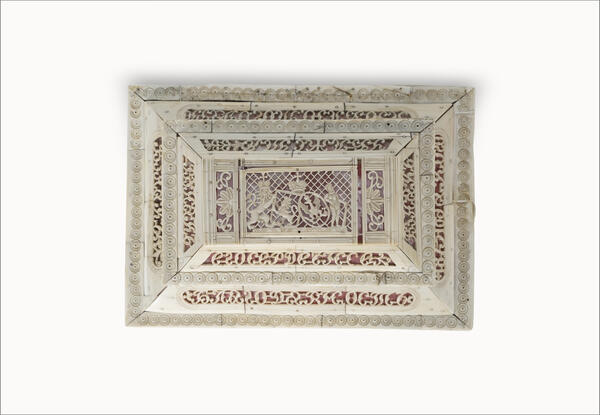

The presented exhibit is a magnificent two-tiered casket on carved curly legs with a lid with four sides. There are inscriptions on the side slopes: “As a sign of heartfelt, as a sign of respect, as a sign of gratitude, in 1873, I give it to whom I love.” As a tribute to fashion trends, its walls are decorated with eastern motifs with figures and dwellings, as well as scenes of rural life.

The Kholmogory school of bone carving has been known since the 17th century. Having absorbed the Northern Russian traditions, as well as the techniques of German, Dutch masters and traditions of the indigenous peoples of the North, the special Kholmogory style finally developed only by the 18th century. It is mainly characterized by openwork designs and finest openwork carving. Fabulous floral ornaments and elegant rocailles are combined with relief images inspired by various plots and decorated with color-filled engraving.

Some of the oldest products are prayer beads, mouthpieces, and combs with the finest teeth. All kinds of boxes and caskets modeled after Kholmogory chests, as well as snuffboxes, photo frames, icons, miniatures and portraits were also popular. Later, the artisans began to make glasses, vases, chess and checkers sets, interior cladding, copies of famous sculptures and decorative compositions on a variety of topics.

The best Kholmogory carvers were invited to work in the Armory Chamber to create items for the royal court. Peter I patronized the masters, providing them with samples of Western bone-cutting art, and Catherine I used Kholmogory carved caskets for personal belongings. Bone products were presented as memorable gifts to important persons, and monasteries and churches commissioned the masters to make various items. Ivan Krusenstern even brought the decorative vases created by the master Nikolay Vereshchagin, presently housed in the Hermitage Museum, on the first Russian circumnavigation of the Earth: those were to be presented to the Japanese emperor, but the embassy refused to accept them.

Many villages in the vicinity of Kholmogory were engaged in this craft. For example, the most significant Russian sculptor of the 18th century, Fedot Shubin, came from a family of bone-cutters from the village of Tyuchkovskaya.

The presented exhibit is a magnificent two-tiered casket on carved curly legs with a lid with four sides. There are inscriptions on the side slopes: “As a sign of heartfelt, as a sign of respect, as a sign of gratitude, in 1873, I give it to whom I love.” As a tribute to fashion trends, its walls are decorated with eastern motifs with figures and dwellings, as well as scenes of rural life.