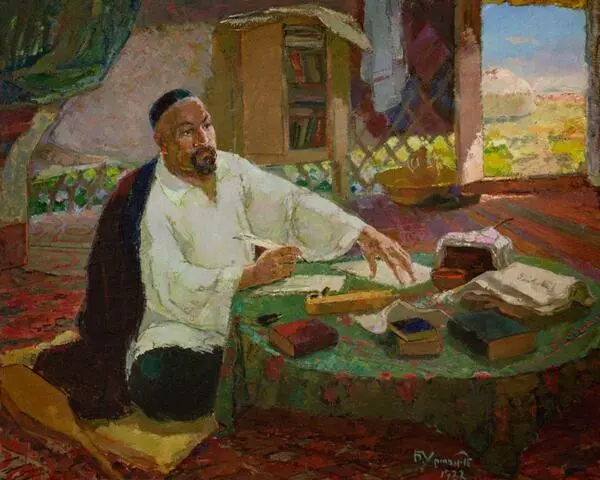

In 1929, during political repressions, artist Baki Urmanche was arrested in his studio in Kazan and sent to the Solovki Special Camp. He returned to his native Kazan 4 years later, but by that moment everything had changed there and he could not live the life he had had before.

With the help of his friends, he moved to Moscow and resumed his creative work. He remembered those times as follows: ‘The large exhibition organized in 1934 gave me an opportunity to return to creative work.

With the help of his friends, he moved to Moscow and resumed his creative work. He remembered those times as follows: ‘The large exhibition organized in 1934 gave me an opportunity to return to creative work.

I saw light at the end of the tunnel. My soul, wounded and empty, tried to hope again. But there was no calm anymore, no steady pace with which I started my way in 1926’. After a quiet period, misfortune came his way again: the artist was given a passport with a ‘minus 39’ mark that meant he was not allowed to work in large cities. And so started his long years of wandering.

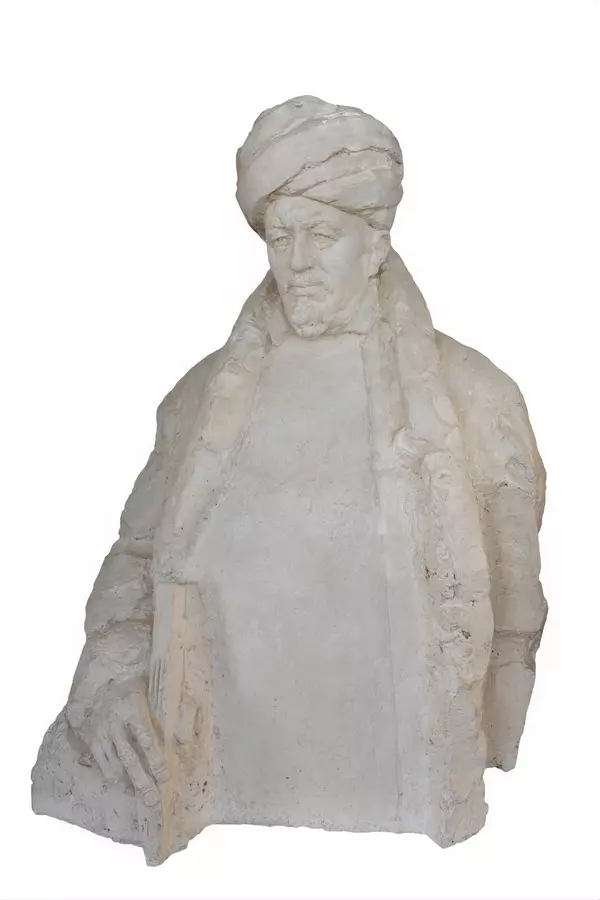

He came back to Kazan to stay only at the end of the 1950s. He did not get a warm welcome: the Artists’ Union did not help him to transport heavy stones for sculptures and gave him no place for working. He had to create one of his most famous sculptures, a marble image of poet Tuqay, in the boiler room of the Trade Workers’ Club, amidst soot and smoke. Several years later, Urmanche managed to buy a studio that soon became to be visited by young artists and journalists.

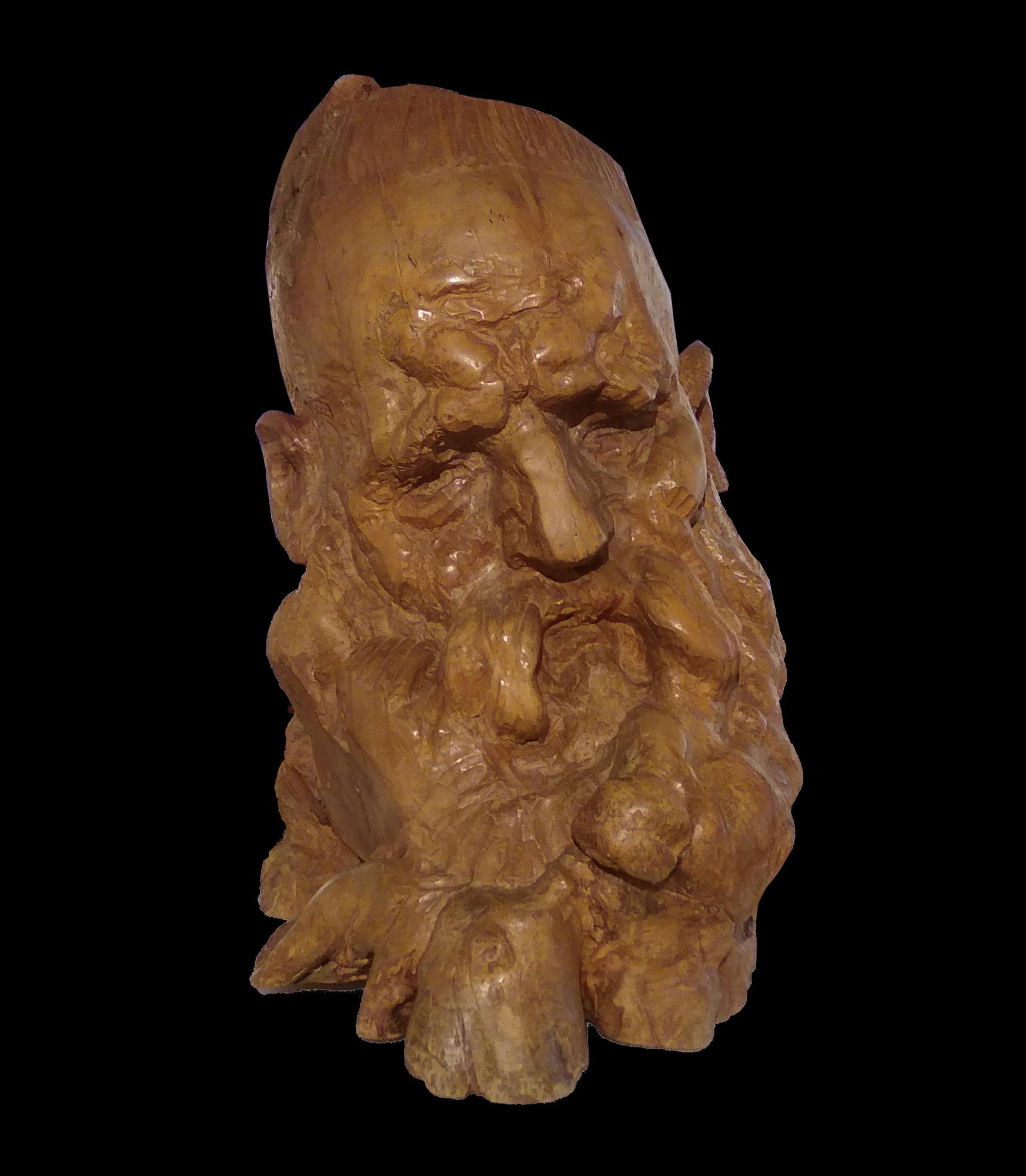

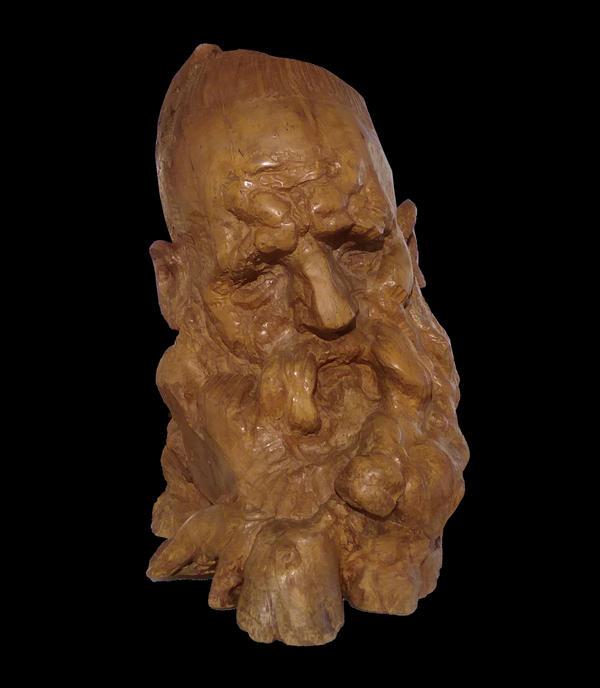

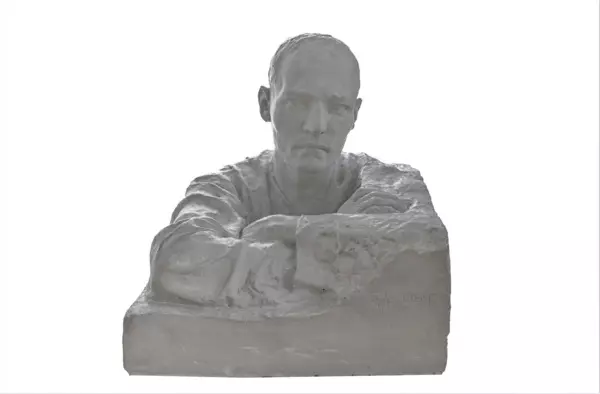

In that studio, he worked on many sculptures: first, he made a clay mould, then a plaster cast, and then created a sculpture in wood or marble. Among those sculptures, there is a wooden one called Sagysh, which forms a kind of a diptych with Spring Melodies. The Tatar word sagysh has several meanings: musing, melancholy, grief, sadness, philosophical meditations.

From a sturdy root of a pear tree, the artist cut the face of a wise old man, lost in deep philosophical contemplation. On his face, ploughed with lines, there are no signs of feebleness or decrepitude. His powerful, bulgy forehead under the skullcap, lightly traced with the sculptor’s chisel, is a sign of great intellect; his tight lips are a sign of strong will and determination. His hand, knobbly and lined, tells us about years of hard work. In Sagysh, Urmanche perfectly conveys the greatness of human spirit.

He came back to Kazan to stay only at the end of the 1950s. He did not get a warm welcome: the Artists’ Union did not help him to transport heavy stones for sculptures and gave him no place for working. He had to create one of his most famous sculptures, a marble image of poet Tuqay, in the boiler room of the Trade Workers’ Club, amidst soot and smoke. Several years later, Urmanche managed to buy a studio that soon became to be visited by young artists and journalists.

In that studio, he worked on many sculptures: first, he made a clay mould, then a plaster cast, and then created a sculpture in wood or marble. Among those sculptures, there is a wooden one called Sagysh, which forms a kind of a diptych with Spring Melodies. The Tatar word sagysh has several meanings: musing, melancholy, grief, sadness, philosophical meditations.

From a sturdy root of a pear tree, the artist cut the face of a wise old man, lost in deep philosophical contemplation. On his face, ploughed with lines, there are no signs of feebleness or decrepitude. His powerful, bulgy forehead under the skullcap, lightly traced with the sculptor’s chisel, is a sign of great intellect; his tight lips are a sign of strong will and determination. His hand, knobbly and lined, tells us about years of hard work. In Sagysh, Urmanche perfectly conveys the greatness of human spirit.