The Crucifixion of Jesus is described in all four Gospels, the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus, and the patristic writings.

Until the 5th century, the Crucifixion was depicted allegorically, for example, as the Cross with a crown of thorns, or the Cross with a half-length figure of Christ above it. In the second quarter of the 5th century, the first images of the crucified Jesus appeared. Old Russian painting adopted the Byzantine iconographic tradition that had developed by the 6th century.

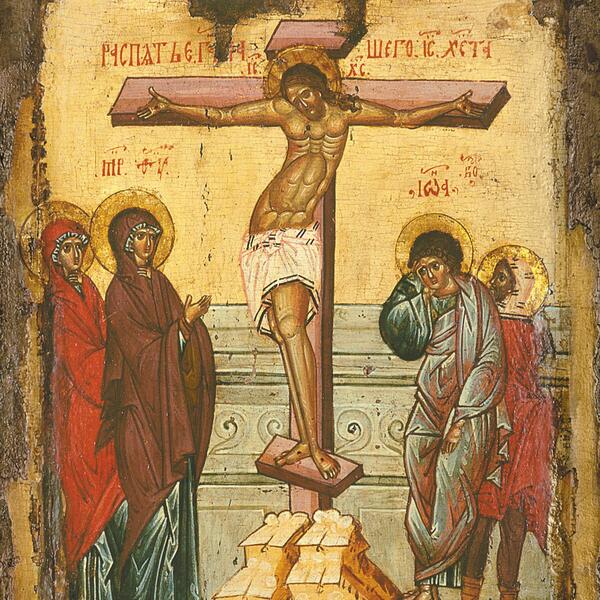

There are three various iconographic versions of the Crucifixion that differ in their composition. The first one (the 14th and 15th centuries) is used in this icon: figures are depicted symmetrically to each side of the Cross: the Mother of God and one of the holy myrrh-bearers on the left, and John the Apostle and the Centurion Longinus on the right. In the second variant, typical of Novgorod icon painting, only the Mother of God and John the Apostle stand near the Cross. In the third type, the criminals crucified next to Jesus are also depicted beside him.

All images have some elements in common. These include the Hill of Golgotha with the Cross erected on it and the black cave with the skull of Adam below. According to the legend first mentioned in the 3rd and 4th centuries, Adam was said to have been buried on the site of the Crucifixion. In one of the Apocryphal books, it is mentioned that during the burial of Adam, Seth the Patriarch placed a seed into his mouth, from which the Precious Wood of the Cross later sprang. The crack in the center of the hill illustrates the words that after the death of Jesus, “the earth did quake, and the rocks rent” (Matthew 27:51).

The figures of those standing in front of Jesus are characterized by a solemn restraint typical of a sacred scene, but nevertheless show dramatic emotions: John the Apostle covers his face with a hand, while the Virgin Mary and, most likely, Mary Magdalene stand with their palms at their necks. The Centurion Longinus, having experienced sympathy for the sorrows of Christ and having found faith, looks at the Savior intently. The faces are painted in a relief and energetic manner.

In the background, we can see the walls of Jerusalem which indicates that Jesus was crucified outside the city.

For the Cross, the artist used the purple color which is rather rare in Russian icon painting. The art expert Valery Lepakhin comments that this color is a mix of black (the color of death) and red (the color of suffering) thus evoking associations with hellfire. To avoid this ambiguity, icon painters intentionally made this color closer to dark blue or pink as in this icon. Archimandrite Raphael Karelin called purple the color of the end.

This is the only example of Novgorod icon painting in the museum collection. Most likely, it was acquired by the museum with the help of the icon restoration artist and historian Alexander Anisimov who delivered a course on Old Russian Art at the museum.

Until the 5th century, the Crucifixion was depicted allegorically, for example, as the Cross with a crown of thorns, or the Cross with a half-length figure of Christ above it. In the second quarter of the 5th century, the first images of the crucified Jesus appeared. Old Russian painting adopted the Byzantine iconographic tradition that had developed by the 6th century.

There are three various iconographic versions of the Crucifixion that differ in their composition. The first one (the 14th and 15th centuries) is used in this icon: figures are depicted symmetrically to each side of the Cross: the Mother of God and one of the holy myrrh-bearers on the left, and John the Apostle and the Centurion Longinus on the right. In the second variant, typical of Novgorod icon painting, only the Mother of God and John the Apostle stand near the Cross. In the third type, the criminals crucified next to Jesus are also depicted beside him.

All images have some elements in common. These include the Hill of Golgotha with the Cross erected on it and the black cave with the skull of Adam below. According to the legend first mentioned in the 3rd and 4th centuries, Adam was said to have been buried on the site of the Crucifixion. In one of the Apocryphal books, it is mentioned that during the burial of Adam, Seth the Patriarch placed a seed into his mouth, from which the Precious Wood of the Cross later sprang. The crack in the center of the hill illustrates the words that after the death of Jesus, “the earth did quake, and the rocks rent” (Matthew 27:51).

The figures of those standing in front of Jesus are characterized by a solemn restraint typical of a sacred scene, but nevertheless show dramatic emotions: John the Apostle covers his face with a hand, while the Virgin Mary and, most likely, Mary Magdalene stand with their palms at their necks. The Centurion Longinus, having experienced sympathy for the sorrows of Christ and having found faith, looks at the Savior intently. The faces are painted in a relief and energetic manner.

In the background, we can see the walls of Jerusalem which indicates that Jesus was crucified outside the city.

For the Cross, the artist used the purple color which is rather rare in Russian icon painting. The art expert Valery Lepakhin comments that this color is a mix of black (the color of death) and red (the color of suffering) thus evoking associations with hellfire. To avoid this ambiguity, icon painters intentionally made this color closer to dark blue or pink as in this icon. Archimandrite Raphael Karelin called purple the color of the end.

This is the only example of Novgorod icon painting in the museum collection. Most likely, it was acquired by the museum with the help of the icon restoration artist and historian Alexander Anisimov who delivered a course on Old Russian Art at the museum.