In the USSR, the development of radio broadcasting was regarded with great attention. In the streets of cities and villages, radio receivers became increasingly common and people began to call them “radio dishes”, or simply “dishes”. Since 1925, wire broadcast receivers have been installed in residential buildings. As a result, the entire territory of the vast country was covered with a network of broadcasting stations.

During the Great Patriotic War, wire broadcasting remained practically the only reliable source of information. It played an exceptional role when it was needed to warn the population or organize the system of civil defense. Those who lived through the years of the war vividly remember how important radio receivers were back then, especially in Leningrad, Moscow and other front-line cities.

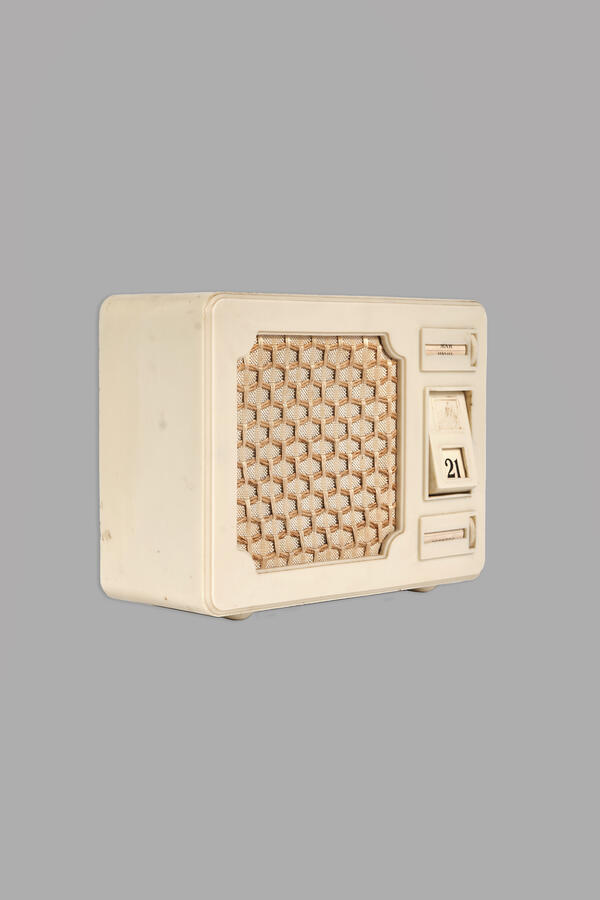

In the late 1940s, wired radio was already used by a significant part of the urban population, and the service began to be extended to the countryside. New models of radio speakers had replaced bulky “dishes”. In the late 1950s — early 1960s, small boxes on the wall or on the shelf, the so-called kitchen “talkers”, became an indispensable item at home and at work. As a rule, they were made exclusively as radio receivers. The receiver could broadcast only one wave, so on the right side it had only one knob — to change the volume.

In March 1964, the Council of Ministers of the RSFSR adopted a resolution on the obligatory presence of a radio broadcasting network in all residential buildings under construction. As a result, radio outlets (radio speakers) were available in all new apartments. Such a radio receiver was a source of information, a music channel, an alarm clock, a means of emergency notification, and an audiobook. The country woke up at six in the morning to the sound of the anthem of the Soviet Union, and the radio went silent at midnight.

Local broadcasting in the USSR was carried out in sixty-nine languages of the peoples of the USSR. The programs tried to cater for all segments of the population, broadcasting programs ranged from “Baby Monitor” and “Pioneer Dawn” for children to “On a Working Noon” for workers, as well as “Literary Readings”, “For Those at Sea”, “Field Mail of Youth”, “Bulletin of the Search for Relatives” and many others. During a power outage, the first channel of the wired All-Union Radio remained working, so it was possible to notify the population about the occurrence of various kinds of emergencies.

During the Great Patriotic War, wire broadcasting remained practically the only reliable source of information. It played an exceptional role when it was needed to warn the population or organize the system of civil defense. Those who lived through the years of the war vividly remember how important radio receivers were back then, especially in Leningrad, Moscow and other front-line cities.

In the late 1940s, wired radio was already used by a significant part of the urban population, and the service began to be extended to the countryside. New models of radio speakers had replaced bulky “dishes”. In the late 1950s — early 1960s, small boxes on the wall or on the shelf, the so-called kitchen “talkers”, became an indispensable item at home and at work. As a rule, they were made exclusively as radio receivers. The receiver could broadcast only one wave, so on the right side it had only one knob — to change the volume.

In March 1964, the Council of Ministers of the RSFSR adopted a resolution on the obligatory presence of a radio broadcasting network in all residential buildings under construction. As a result, radio outlets (radio speakers) were available in all new apartments. Such a radio receiver was a source of information, a music channel, an alarm clock, a means of emergency notification, and an audiobook. The country woke up at six in the morning to the sound of the anthem of the Soviet Union, and the radio went silent at midnight.

Local broadcasting in the USSR was carried out in sixty-nine languages of the peoples of the USSR. The programs tried to cater for all segments of the population, broadcasting programs ranged from “Baby Monitor” and “Pioneer Dawn” for children to “On a Working Noon” for workers, as well as “Literary Readings”, “For Those at Sea”, “Field Mail of Youth”, “Bulletin of the Search for Relatives” and many others. During a power outage, the first channel of the wired All-Union Radio remained working, so it was possible to notify the population about the occurrence of various kinds of emergencies.