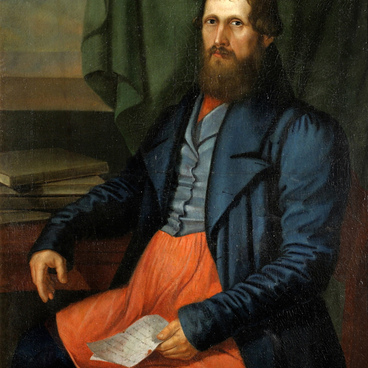

The Uglich Museum houses a portrait of the honorary citizen Matvey Sergeyevich Surin. It was painted by the provincial artist Ivan Vasilyevich Tarkhanov, the son of an Uglich parish priest.

Interestingly, he first painted a portrait of Matvey Surin in 1829 depicting him as the head of the family and master of the house. Apart from him, the artist also portrayed other family members. In the first half of the 19th century, the merchant class gained importance: instead of being common ironware sellers, merchants became recognized as “city fathers”. Having family portraits was a sign of wealth and status.

Fourteen years later, Matvey Surin’s son asked Tarkhanov to paint another portrait of his father who had already died by that time. This portrait served as a monument: the uniform was painted from life, while the man’s face was depicted exactly the same as in the portrait dated 1829. It aimed not only to eternalize the memory of Matvey Surin but also to show his important role and place in the life of the city. He was a member of the city council governing the merchant and bourgeois class, and in 1839, he resigned from the position of mayor — with recognition of his services and the honorary right to continue wearing the uniform.

The honorary citizen Matvey Surin died in October 1842 which is evidenced by the record made by his son, “He was 69 years 3 months 18 days old.” The son glorified his father and turned his funeral into a celebration of his life, “The funeral service was performed at the Kazanskaya Church by 30 priests, 2 archimandrites, 14 deacons, and 60 sextons, and the funeral reception was attended by 320 people.” Later, he commissioned paired portraits which symbolized that he had become equal to his father. The other portrait in the pair titled “Surin Junior” depicts the son who served in the city council and wore an embroidered jacket emphasizing the importance of his family to the local community and the succession of its representatives in elected offices.

Paired portraits of a father and a son were rather rare in the work of provincial artists. After the revolution of 1917, it was inappropriate and even dangerous to cherish the memory of former mayors. The Surin family archive was on the verge of being lost. Luckily, in the 1970s, part of the archive was saved from being sent to a landfill and donated to the museum.

Interestingly, he first painted a portrait of Matvey Surin in 1829 depicting him as the head of the family and master of the house. Apart from him, the artist also portrayed other family members. In the first half of the 19th century, the merchant class gained importance: instead of being common ironware sellers, merchants became recognized as “city fathers”. Having family portraits was a sign of wealth and status.

Fourteen years later, Matvey Surin’s son asked Tarkhanov to paint another portrait of his father who had already died by that time. This portrait served as a monument: the uniform was painted from life, while the man’s face was depicted exactly the same as in the portrait dated 1829. It aimed not only to eternalize the memory of Matvey Surin but also to show his important role and place in the life of the city. He was a member of the city council governing the merchant and bourgeois class, and in 1839, he resigned from the position of mayor — with recognition of his services and the honorary right to continue wearing the uniform.

The honorary citizen Matvey Surin died in October 1842 which is evidenced by the record made by his son, “He was 69 years 3 months 18 days old.” The son glorified his father and turned his funeral into a celebration of his life, “The funeral service was performed at the Kazanskaya Church by 30 priests, 2 archimandrites, 14 deacons, and 60 sextons, and the funeral reception was attended by 320 people.” Later, he commissioned paired portraits which symbolized that he had become equal to his father. The other portrait in the pair titled “Surin Junior” depicts the son who served in the city council and wore an embroidered jacket emphasizing the importance of his family to the local community and the succession of its representatives in elected offices.

Paired portraits of a father and a son were rather rare in the work of provincial artists. After the revolution of 1917, it was inappropriate and even dangerous to cherish the memory of former mayors. The Surin family archive was on the verge of being lost. Luckily, in the 1970s, part of the archive was saved from being sent to a landfill and donated to the museum.