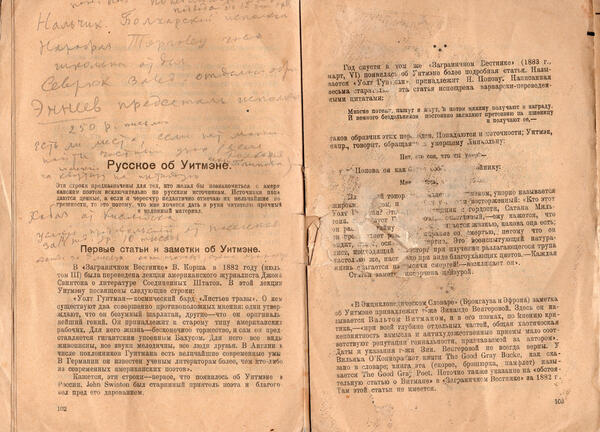

Walt Whitman became known to the Russian public for the first time from an 1861 issue of the literary magazine “Otechestvennye Zapiski” (“Notes of the Fartherland”). The article accused the poet of immorality, citing a long list of issues with his writings. 20 years later, Valentin Korsh published an article in the journal “Foreign Bulletin” by John Swinton, who defined the main topic of Whitman’s work,

The Poetry of the Coming Democracy

For him, life is an endless triumph.

A collection of poems by Walt Whitman translated by Korney Chukovsky was first printed in the Russian Empire in 1913. The latter also wrote a foreword. However, the publication was withdrawn from circulation due to censorship. The copies were to be destroyed. The collection remained banned until 1917.

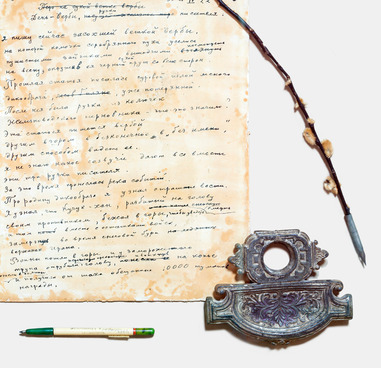

Only in 1919, thanks to increased interest of Russian and Western readers in the poet, the collection was published again. Velimir Khlebnikov never parted with this book, rereading it ad nauseam: its title page is missing, the pages are worn out and replete with marks.

The attitude towards Whitman remained ambivalent. The British utopian socialist Edward Carpenter admitted that he did not know “another such book”. He added, “it became part of my blood.” Conversely, the Norwegian writer Knut Hamsun noted that the poet was nothing more than a “kind, funny savage.” Konstantin Balmont spoke of Whitman as “a poet with the body of a gladiator”, Yuly Eichenwald called him “a drunken master of the universe”, while Ilya Repin — “a fool for Christ, an apostle”.

Velimir Khlebnikov claimed that Walt Whitman was a “cosmic psycho-receiver.” Whitman’s poetic innovations, free verse, intonational looseness, as well as his pantheism, consonant with Khlebnikov’s “The One, the Only Book”, were in tune with the Russian futurist’s style.

In the article “Whitman and the Futurists”, Chukovsky wrote that “the Russian futurists are trying to join… the poetry of the coming times” and called Whitman the only poet who deserved the recognition of the futurists.

His remark about the similarity of Khlebnikov’s “Zverinets” (“Menagerie”) and Whitman’s poem “Song of Myself” led to a heated debate. According to Chukovsky, “the Moscow futurist Viktor Khlebnikov… openly mimicked Whitman” in how he “soared above space and time, in some kind of prophetic delirium… <capturing> the entire universe with his eyes.”

Khlebnikov objected that he wrote “Menagerie” before getting acquainted with Whitman’s work, and stated, “if having the same number of eyes as you, means imitating you, if looking at the same sun as you, means imitating you, then I imitate Whitman.” In his declining years, Korney Chukovsky partially revised his opinion.

The exhibit is a bibliographic rarity. It came to the museum in 1997 as a gift of May Petrovich Miturich-Khlebnikov (Moscow).