The exhibition presents samples of fabrics with printed patterns. Printed art has been known since ancient times; the technology of painting with a printed method appeared in Russia already in the early Middle Ages. The ‘golden age’ of printing art fell on the 17th and 18th centuries.

For a long time, till end of the 17th century, mainly oil paints were used in Russia to perform prints. The pattern was applied to the fabric using carved woodblocks. Oil paint roughened the fabric, cracked, did not tolerate washing well, so the craftsmen tried to find other options.

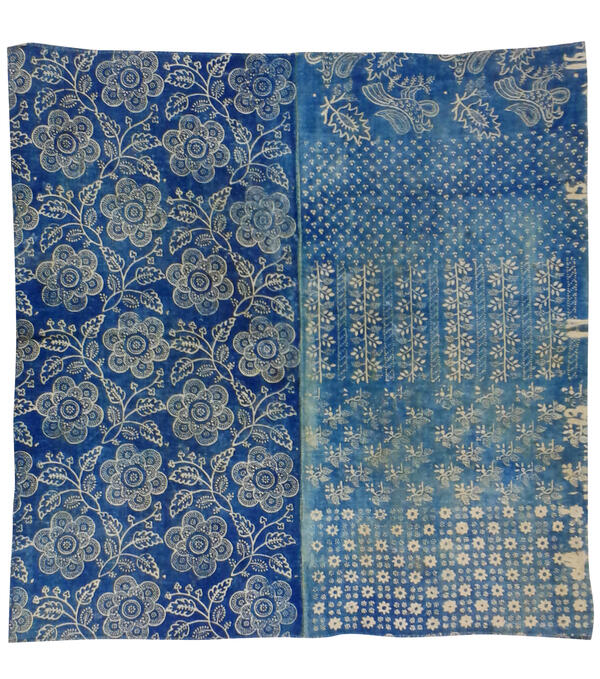

Another method to produce printed cloth is ‘vat’ method, in which a special composition was applied to the fabric using printed boards beforehand to protect it from dye — ‘vapa’ (consisted of wax, clay and starch). After applying the ‘vapa’, canvases were immersed in specially adapted boilers (cauldrons). Most often, the fabric was dyed blue in this way. Mainly natural dyes were used: black dyes were made from wood soot, blue — from indigo infusion.

The hand-made oil printing was gradually replaced by factory fabrics already in the 18th century, and vat canvases existed until the first decades of the 20th century. Printed fabrics are popularly called ‘motley’ due to their colorfulness, variety of patterns and relatively low cost. They were widely used in clothing and interior design. The pattern of the print was changing. For example, in the 17th century, small geometric and lush plant patterns were popular. In the 18th century, the ornament became lighter and more graceful. In addition to floral patterns, secular motifs were popular in the peasant print: flower garlands tied with ribbons, Turkish paisley cucumbers, ostrich feathers. In the 19thcentury, the pattern became more strict and small. Simple geometric and floral designs were back in fashion.

Printing on fabric required working hands and special equipment. The craftsmen united into enterprises called ‘establishments’. Orders were taken at fairs. For this, they learned how to make samples — strips of canvas with various patterns — one of which is presented in the showcase. It was a kind of album for choosing a pattern.

For a long time, till end of the 17th century, mainly oil paints were used in Russia to perform prints. The pattern was applied to the fabric using carved woodblocks. Oil paint roughened the fabric, cracked, did not tolerate washing well, so the craftsmen tried to find other options.

Another method to produce printed cloth is ‘vat’ method, in which a special composition was applied to the fabric using printed boards beforehand to protect it from dye — ‘vapa’ (consisted of wax, clay and starch). After applying the ‘vapa’, canvases were immersed in specially adapted boilers (cauldrons). Most often, the fabric was dyed blue in this way. Mainly natural dyes were used: black dyes were made from wood soot, blue — from indigo infusion.

The hand-made oil printing was gradually replaced by factory fabrics already in the 18th century, and vat canvases existed until the first decades of the 20th century. Printed fabrics are popularly called ‘motley’ due to their colorfulness, variety of patterns and relatively low cost. They were widely used in clothing and interior design. The pattern of the print was changing. For example, in the 17th century, small geometric and lush plant patterns were popular. In the 18th century, the ornament became lighter and more graceful. In addition to floral patterns, secular motifs were popular in the peasant print: flower garlands tied with ribbons, Turkish paisley cucumbers, ostrich feathers. In the 19thcentury, the pattern became more strict and small. Simple geometric and floral designs were back in fashion.

Printing on fabric required working hands and special equipment. The craftsmen united into enterprises called ‘establishments’. Orders were taken at fairs. For this, they learned how to make samples — strips of canvas with various patterns — one of which is presented in the showcase. It was a kind of album for choosing a pattern.