Before special office knives were available, an envelope with a letter or the pages of a new book or magazine were cut with dagger-type blades of either household or combat knives. The tradition of cutting rather than tearing paper appears to have been around since at least the 16th century.

A stationery knife was essential for any reader, because even in the mid-20th century it was impossible to simply open a large print publication immediately after purchase. Printing houses did not have hydraulic presses and factory knives designed to separate pages throughout the entire volume. To form a book or magazine, the necessary number of large-format sheets were folded over several times (one sheet had about twenty pages), stitched together in the right order and delivered to the binder in this form. The buyer had to cut the pages himself, as carefully as possible so as not to damage the printed text.

Special paper knives emerged and quickly became common in the 18th and 19th centuries The first models were made in the form of ordinary knives with a diamond-shaped blade that widened from the hilt to the tip. Very soon this tool found its place in the offices where people had to do reading, and it became a part of a clerk’s kit along with an inkwell, a quill and a seal.

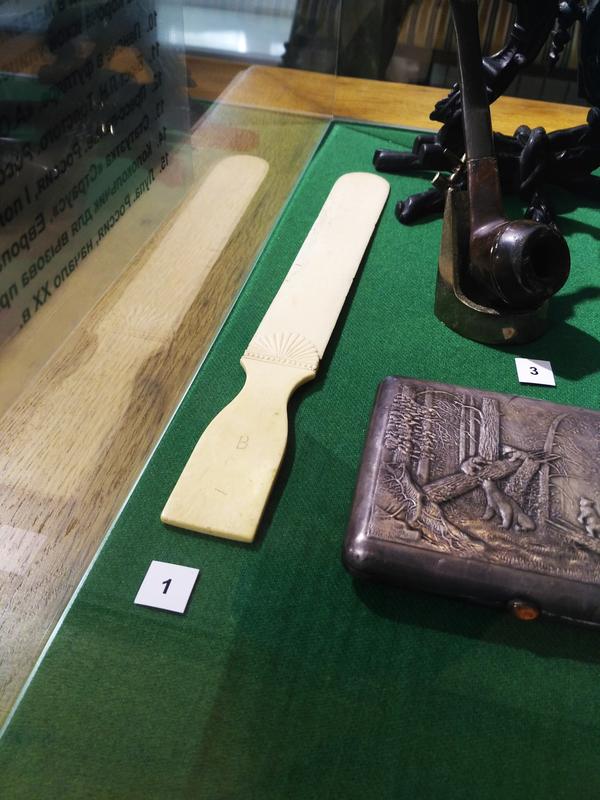

The long handle and curved blade, slightly sharpened on both sides, made these knives safe, and the decorative design made them a unique accessory for an interior, or desk. Paper knives varied in size, material and design. Expensive models were made of precious and non-ferrous metals: gold, silver, bronze and copper, and also of stone, ivory, wood, and even volcanic tuff, sometimes different materials were combined. The decoration of the hilt, which was always made by hand, featured precious stones, mother-of-pearl and pearls. Only wealthy people could afford such exquisite items, the knives were cherished and passed down through generations. They were usually kept in special leather cases together with other writing utensils. There were also more democratic models — pewter, copper or brass ones. However, even these affordable knives were distinguished by their discreet but elegant finish.

The knife in the exhibition has an open fan-shaped carving.

A stationery knife was essential for any reader, because even in the mid-20th century it was impossible to simply open a large print publication immediately after purchase. Printing houses did not have hydraulic presses and factory knives designed to separate pages throughout the entire volume. To form a book or magazine, the necessary number of large-format sheets were folded over several times (one sheet had about twenty pages), stitched together in the right order and delivered to the binder in this form. The buyer had to cut the pages himself, as carefully as possible so as not to damage the printed text.

Special paper knives emerged and quickly became common in the 18th and 19th centuries The first models were made in the form of ordinary knives with a diamond-shaped blade that widened from the hilt to the tip. Very soon this tool found its place in the offices where people had to do reading, and it became a part of a clerk’s kit along with an inkwell, a quill and a seal.

The long handle and curved blade, slightly sharpened on both sides, made these knives safe, and the decorative design made them a unique accessory for an interior, or desk. Paper knives varied in size, material and design. Expensive models were made of precious and non-ferrous metals: gold, silver, bronze and copper, and also of stone, ivory, wood, and even volcanic tuff, sometimes different materials were combined. The decoration of the hilt, which was always made by hand, featured precious stones, mother-of-pearl and pearls. Only wealthy people could afford such exquisite items, the knives were cherished and passed down through generations. They were usually kept in special leather cases together with other writing utensils. There were also more democratic models — pewter, copper or brass ones. However, even these affordable knives were distinguished by their discreet but elegant finish.

The knife in the exhibition has an open fan-shaped carving.