The “Portrait of an Unknown Man with a Scroll” entered the Uglich Museum in the mid-20th century and, due to its poor condition, was kept in the reserve collection for many years. The painting needed a competent science-based restoration that would be able to bring it to the image created by the artist.

After the 1917 Bolshevik revolution, when all the estates and stately homes were nationalized, the portrait painter and museum manager Alexander Konstantinovich Gusev, when selecting and saving antique objects and works of art, compiled descriptions of a number of old portraits that had been discovered in the house of the Kochurikhins on the left bank of the Volga. Subsequently, all these portraits were transferred to the museum.

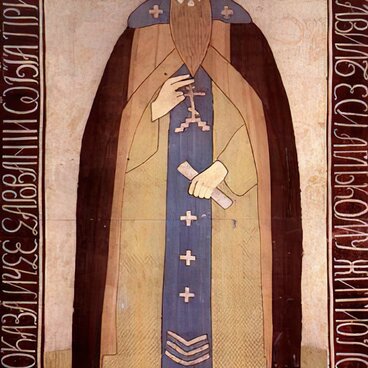

In the “Portrait of an Unknown Man with a Scroll”, the image of the “confirmed dissenter” Grigory Ilyich Kochurikhin, described in 1921 by Alexander Gusev, can be recognized. An intense protest against the “Nikonian church”, the state of irreconcilable dispute with it and between the different and often warring dissident creeds themselves, the acuteness of personal experience — everything forced its way out in the form of texts and faces, letters about faith, edifying drawings and portraits. The manuscript on parchment, or a “chartaceous letter”, apparently had a fundamental significance. The image of the man himself is focused not on individual features, but on a certain canon that developed among the Old Believers in the image of “elders”: a haggard face, a high forehead, sunken temples, an indefinite and at the same time intense look, and an elongated “flat” figure.

In Uglich, a well-known center of active opposition to “Nikonianism” (that is, the reformed official church), was a prayer room in a spacious house of the merchant family of the Vyzhilovs that was located near the city center. Numerous attempts to inspect and close it invariably ended in failure: the prayer room mysteriously became “invisible” to inspectors sent to the city. Another nest of dissenters was the left-bank Uglich, where large families of “confirmed dissenters” lived side by side for decades. This environment is displayed in the museum by a significant complex of exhibits — including engravings representing prominent dissenters, drawings explaining the order of worship and the meaning of attributes, books, and a number of painted portraits. The image of an “elder” hardly needed a paired female image; the painting was, in principle, intended for like-minded people outside the family circle, to whom the once-readable text of the scroll was addressed.

After the 1917 Bolshevik revolution, when all the estates and stately homes were nationalized, the portrait painter and museum manager Alexander Konstantinovich Gusev, when selecting and saving antique objects and works of art, compiled descriptions of a number of old portraits that had been discovered in the house of the Kochurikhins on the left bank of the Volga. Subsequently, all these portraits were transferred to the museum.

In the “Portrait of an Unknown Man with a Scroll”, the image of the “confirmed dissenter” Grigory Ilyich Kochurikhin, described in 1921 by Alexander Gusev, can be recognized. An intense protest against the “Nikonian church”, the state of irreconcilable dispute with it and between the different and often warring dissident creeds themselves, the acuteness of personal experience — everything forced its way out in the form of texts and faces, letters about faith, edifying drawings and portraits. The manuscript on parchment, or a “chartaceous letter”, apparently had a fundamental significance. The image of the man himself is focused not on individual features, but on a certain canon that developed among the Old Believers in the image of “elders”: a haggard face, a high forehead, sunken temples, an indefinite and at the same time intense look, and an elongated “flat” figure.

In Uglich, a well-known center of active opposition to “Nikonianism” (that is, the reformed official church), was a prayer room in a spacious house of the merchant family of the Vyzhilovs that was located near the city center. Numerous attempts to inspect and close it invariably ended in failure: the prayer room mysteriously became “invisible” to inspectors sent to the city. Another nest of dissenters was the left-bank Uglich, where large families of “confirmed dissenters” lived side by side for decades. This environment is displayed in the museum by a significant complex of exhibits — including engravings representing prominent dissenters, drawings explaining the order of worship and the meaning of attributes, books, and a number of painted portraits. The image of an “elder” hardly needed a paired female image; the painting was, in principle, intended for like-minded people outside the family circle, to whom the once-readable text of the scroll was addressed.