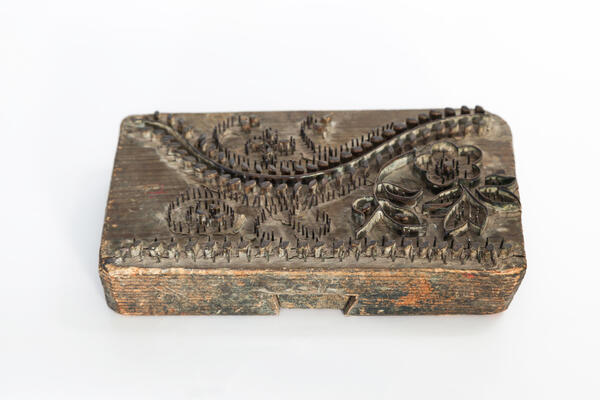

The woodblock on display in the Komi-Permyak Museum was brought by the museum founder Pyotr Ivanovich Subbotin-Permyak from an ethnographic expedition aimed at studying the decorative patterns of the Permyak region. This one-layer woodblock, or so-called manera, is of rectangular shape, with a wedge for the handle on the reverse side. On the obverse, copper plates, pins and wooden pegs set a floral ornament in the form of a flower with five petals and leaves. The bottom border is framed by a smoothly curved stem. Such a board was used to print a pattern on tablecloths and dubas — sarafans made of dyed canvas.

Printing with vat dyes — dyeing fabric in different shades of blue with light patterns — was widely used in the North and Central regions of Russia in the 19th century. At first, a craftsman applied the pattern to the fabric with the help of a woodblock, soaked in a special solution of copper vitriol or wax. It was called vapa and protected the pattern from being pigmented. The fabric was then dried and dyed in the main color by dipping it into a special vat. The printed patterns remained light due to the chemical reaction. The entire process took an experienced craftsman two to three hours.

It was the village men, the “sinilshchiki” (from the Russian siniy — indigo), who carried out the toxic work. They sold their goods and woodblocks at all major fairs. Every printer gathered his own collection of patterns from dozens and hundreds of stamps. They made small woodblocks with vegetative and geometric patterns. There were also images of pagan solar signs and birds with their wings spread. The composition of the pattern usually had various elements alternating horizontally, vertically or in a chessboard pattern.

Mass vat dye printing was no longer used in the first third of the 20th century, when the Industrial Revolution brought about machine labor in place of manual work. The ancient art of manual textile printing with its lively and varied colorful patterns has left a rich legacy of high artistic value. As traditions are being revived, the woodblock printing craft is returning as a local specialty to some regions now; the hand-made items created with the help of ancient technology are beautiful and authentic souvenirs.

Printing with vat dyes — dyeing fabric in different shades of blue with light patterns — was widely used in the North and Central regions of Russia in the 19th century. At first, a craftsman applied the pattern to the fabric with the help of a woodblock, soaked in a special solution of copper vitriol or wax. It was called vapa and protected the pattern from being pigmented. The fabric was then dried and dyed in the main color by dipping it into a special vat. The printed patterns remained light due to the chemical reaction. The entire process took an experienced craftsman two to three hours.

It was the village men, the “sinilshchiki” (from the Russian siniy — indigo), who carried out the toxic work. They sold their goods and woodblocks at all major fairs. Every printer gathered his own collection of patterns from dozens and hundreds of stamps. They made small woodblocks with vegetative and geometric patterns. There were also images of pagan solar signs and birds with their wings spread. The composition of the pattern usually had various elements alternating horizontally, vertically or in a chessboard pattern.

Mass vat dye printing was no longer used in the first third of the 20th century, when the Industrial Revolution brought about machine labor in place of manual work. The ancient art of manual textile printing with its lively and varied colorful patterns has left a rich legacy of high artistic value. As traditions are being revived, the woodblock printing craft is returning as a local specialty to some regions now; the hand-made items created with the help of ancient technology are beautiful and authentic souvenirs.