The five-ruble banknote was one of the most popular in the Russian Empire and in post-revolutionary Russia. It was also among the most interestingly designed ones.

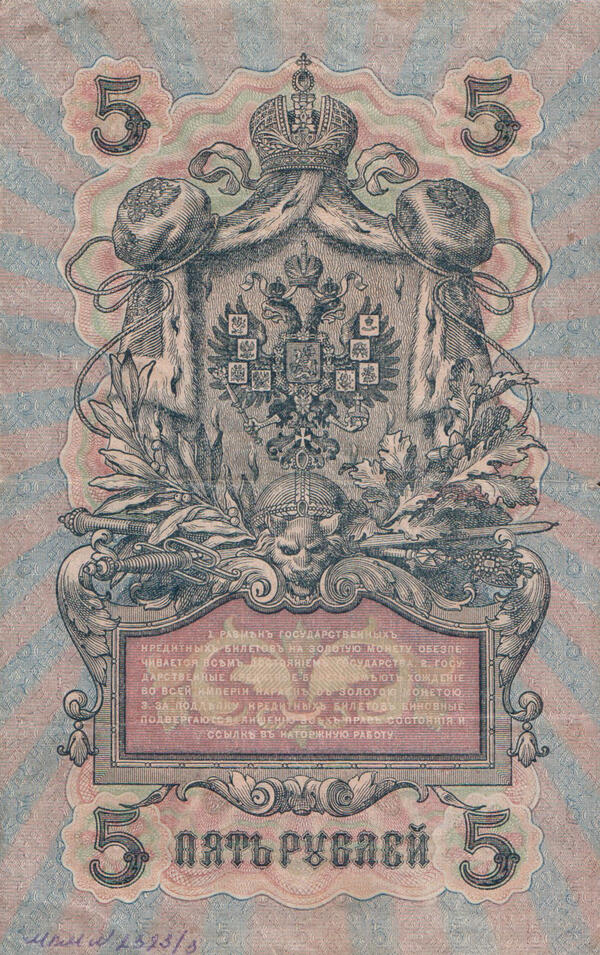

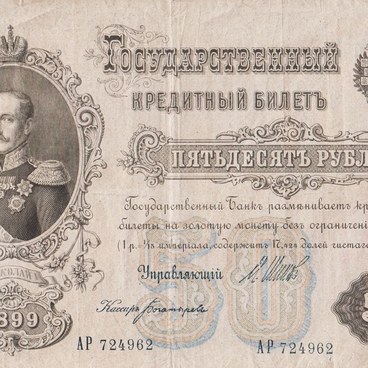

The displayed banknote was designed in 1909 and differed considerably from its 1898 predecessor, retaining, among the few similarities, the prevalence of the blue color. The banknote was vertically oriented. It had an intricate border, which framed the obverse with the denomination and the numbers of the banknote. The elaborate design became a model for future design of banknotes with denominations of 100 and 500 rubles and showed the skills of the artists and workers of the State Securities Procurement Expedition.

The presented denomination was rather high for Russia of the early 20th century, taking into account that the average wage of a worker was 25–35 rubles. The stability of Russia’s financial system, ensured by the reforms of Count Sergei Yulievich Witte, contributed to the fact that throughout the early 20th century the five-ruble banknote remained quite valuable as a means of payment.

The monetary system of Russia, like those of most other European countries, received a serious shake-up when the World War broke out. Because of the need to adjust industrial production in order to maximize results for the supply of the front, the state began to actively intervene in the economy, using previously untested mechanisms to manage it. The consequent disruption of the production and distribution system also contributed to the fall in the purchasing power of the ruble. The ensuing inflation was not overcome until the fall of the monarchy, and remained an inseparable part of the country’s economic life for several years afterward. However, the issue of banknotes in denominations of five rubles had been carried out before the revolutionary events in the country on a rather large scale, which, on the one hand, indicated its popularity, and on the other, the gradual depreciation of money, as the denomination in question was increasingly losing its purchasing power.

When the Provisional Government came to power, the printing of imperial money continued, but as it was still in short supply, the new authorities resorted to a trick. The banknote number was shortened: instead of six digits they used three, which simplified the accelerated issue of money and resulted in a sharp increase in the number of five-ruble banknotes. But at the same time the galloping inflation devalued the ruble more and more.

The displayed banknote was designed in 1909 and differed considerably from its 1898 predecessor, retaining, among the few similarities, the prevalence of the blue color. The banknote was vertically oriented. It had an intricate border, which framed the obverse with the denomination and the numbers of the banknote. The elaborate design became a model for future design of banknotes with denominations of 100 and 500 rubles and showed the skills of the artists and workers of the State Securities Procurement Expedition.

The presented denomination was rather high for Russia of the early 20th century, taking into account that the average wage of a worker was 25–35 rubles. The stability of Russia’s financial system, ensured by the reforms of Count Sergei Yulievich Witte, contributed to the fact that throughout the early 20th century the five-ruble banknote remained quite valuable as a means of payment.

The monetary system of Russia, like those of most other European countries, received a serious shake-up when the World War broke out. Because of the need to adjust industrial production in order to maximize results for the supply of the front, the state began to actively intervene in the economy, using previously untested mechanisms to manage it. The consequent disruption of the production and distribution system also contributed to the fall in the purchasing power of the ruble. The ensuing inflation was not overcome until the fall of the monarchy, and remained an inseparable part of the country’s economic life for several years afterward. However, the issue of banknotes in denominations of five rubles had been carried out before the revolutionary events in the country on a rather large scale, which, on the one hand, indicated its popularity, and on the other, the gradual depreciation of money, as the denomination in question was increasingly losing its purchasing power.

When the Provisional Government came to power, the printing of imperial money continued, but as it was still in short supply, the new authorities resorted to a trick. The banknote number was shortened: instead of six digits they used three, which simplified the accelerated issue of money and resulted in a sharp increase in the number of five-ruble banknotes. But at the same time the galloping inflation devalued the ruble more and more.