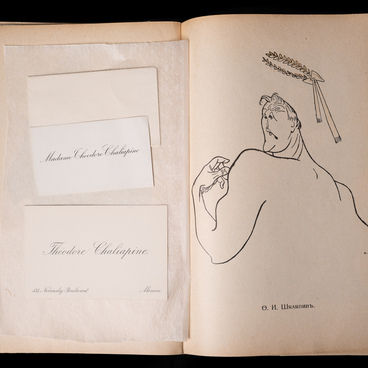

Feodor Chaliapin started to master the skill of putting on makeup quite early on in his career as a stage actor. Actors and later artists became his first guides in this field.

One of Isaac Levitan’s students recounted a conversation that occurred between the landscapist and the singer, “I suspect you, Feodor Ivanovich, might do some painting, too?” Levitan once asked Chaliapin, to which the latter replied that he only did it on his own skin, alluding to his skill at putting on makeup.

For each role Chaliapin used makeup not only for his face and neck, but also for his hands and, if necessary, his body. It was a remarkable innovation at the time. “When I went onto the stage dressed in my costume and made up, ” Chaliapin wrote of his first performance as Mephistopheles in Milan, “it made a real sensation, so flattering to me. Actors, chorus singers, even the workers surrounded me, marveling and admiring, like children; they touched and felt me with their fingers, and seeing that my muscles are painted, went into raptures.”

Even after Chaliapin had created a particular onstage character, he would continue refining it. The Art historian Eduard Aleksandrovich Stark noted that the actor was constantly changing his makeup, seeking greater expressiveness. The makeup for Mephistopheles alone had four main variations, apart from those made in between.

Chaliapin’s makeup was designed for large stages and huge venues. The artist applied and shaded colors with his fingers, “as though molding his face” with broad and contrasting strokes. Up close, this makeup looked like a chaotic combination of strokes, but on a huge opera stage it produced an amazing visual effect.

By changing his makeup throughout the performance, Chaliapin emphasized the inner development of the character. For example, in “Boris Godunov”, the makeup altered in each scene, and the audience watched as “suffering and Macbethean anguish eat away at the man, ” as wrinkles appear and deepen, as gray hair begins to show through on his head and in his beard.

Chaliapin also applied makeup to his accessories. When acting as Yeryomka, he even painted his valenki. When certain scenes in “Don Quixote” required to bring a horse onto the stage, it was “painted” on Chaliapin’s instructions. In an interview on the Monte Carlo premiere of “Don Quixote” Chaliapin said,

One of Isaac Levitan’s students recounted a conversation that occurred between the landscapist and the singer, “I suspect you, Feodor Ivanovich, might do some painting, too?” Levitan once asked Chaliapin, to which the latter replied that he only did it on his own skin, alluding to his skill at putting on makeup.

For each role Chaliapin used makeup not only for his face and neck, but also for his hands and, if necessary, his body. It was a remarkable innovation at the time. “When I went onto the stage dressed in my costume and made up, ” Chaliapin wrote of his first performance as Mephistopheles in Milan, “it made a real sensation, so flattering to me. Actors, chorus singers, even the workers surrounded me, marveling and admiring, like children; they touched and felt me with their fingers, and seeing that my muscles are painted, went into raptures.”

Even after Chaliapin had created a particular onstage character, he would continue refining it. The Art historian Eduard Aleksandrovich Stark noted that the actor was constantly changing his makeup, seeking greater expressiveness. The makeup for Mephistopheles alone had four main variations, apart from those made in between.

Chaliapin’s makeup was designed for large stages and huge venues. The artist applied and shaded colors with his fingers, “as though molding his face” with broad and contrasting strokes. Up close, this makeup looked like a chaotic combination of strokes, but on a huge opera stage it produced an amazing visual effect.

By changing his makeup throughout the performance, Chaliapin emphasized the inner development of the character. For example, in “Boris Godunov”, the makeup altered in each scene, and the audience watched as “suffering and Macbethean anguish eat away at the man, ” as wrinkles appear and deepen, as gray hair begins to show through on his head and in his beard.

Chaliapin also applied makeup to his accessories. When acting as Yeryomka, he even painted his valenki. When certain scenes in “Don Quixote” required to bring a horse onto the stage, it was “painted” on Chaliapin’s instructions. In an interview on the Monte Carlo premiere of “Don Quixote” Chaliapin said,