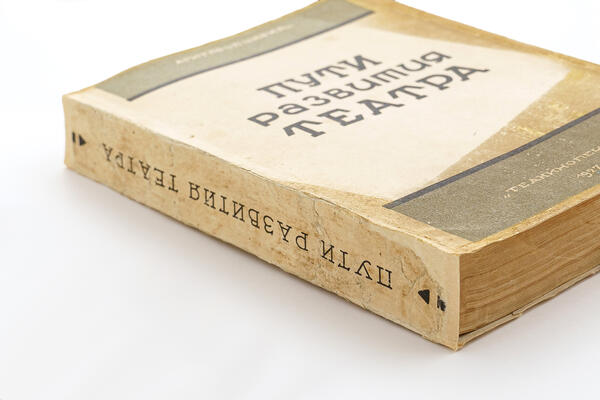

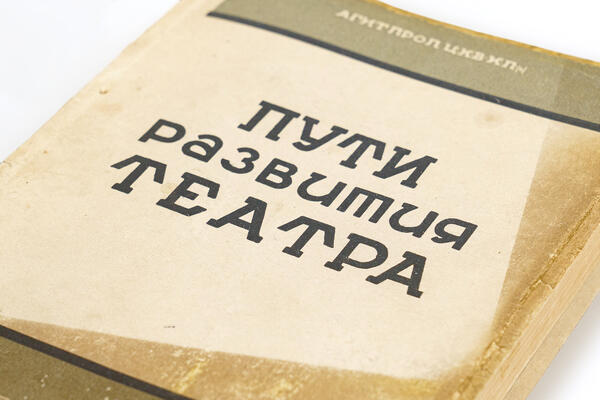

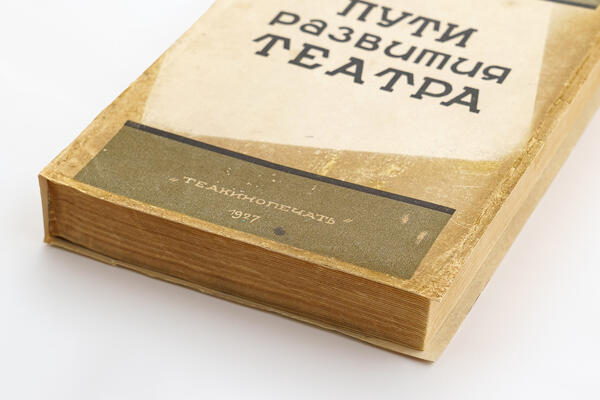

The book “Ways of Theater Development” is interesting because it contains a verbatim report of a meeting on theater issues at the agitation and propaganda section of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks held in May 1927. Mikhail Afanasyevich studied it carefully and wrote the numbers of pages where his plays were mentioned on the title page of the book. This verbatim report and many newspaper articles for the first half of 1927 show that there was a lot written about Bulgakov’s prose and especially his plays, mostly in a negative way.

After the premiere of “The Days of the Turbins” in 1926, the play was accused of “rehabilitation of the White Guard”, “perversion of the civil war and artistic truth”, and Bulgakov himself was accused of “bourgeoisie” and “philistinism”. Some critics recognized that the play has some successful points, but described them as “anti-revolutionary”. At the same time, the play “The Days of the Turbins” was still running at the Moscow Art Theater with a full house: it was next to impossible to obtain tickets for the performance.

But the longer and more successful the performance went on, the more fierce the attacks became. There were the following comments, “counter-revolutionary rot” or “a spit of white guards’ emigrants” on the “hot iron of the revolution”. “The Days of the Turbins” was removed from the repertoire in April 1929 under the critics’ pressure. But in 1932 the play was restored. It is known that General Secretary of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks Joseph Stalin loved this play. “Why are Bulgakov’s plays so often performed on stage? Because, there must be a lack of suitable plays for staging. When there is no choice, even ‘The Days of the Turbins’ is good,” he explained in a letter to the Soviet writer Vladimir Bill-Belotserkovsky.

This anti-Bulgakov campaign in the press of the 1920s is later reflected in “The Master and Margarita”, where the Master is persecuted for his unpublished novel about Pontius Pilate.

“The articles, please note, did not cease. I laughed at the first of them. But the more of them that appeared, the more my attitude towards them changed. The second stage was one of astonishment. Some rare falsity and insecurity could be sensed literally in every line of these articles, despite their threatening and confident tone. I had the feeling, and I couldn’t get rid of it, that the authors of these articles were not saying what they wanted to say, and that their rage sprang precisely from that,” said the Master in the chapter “The Appearance of the Hero.”