Konstantin Istomin became interested in art in his childhood. He studied at art studios in Kharkov and Vladivostok, where his family lived in various years. After the 1905 Workers’ Revolt, Istomin left for Germany, where he studied at Simon Hollosy’s art school in Munich. After four years, he returned to Moscow, where he continued to study at Moscow University in the arts department. Then he was drafted to fight in the war, and upon his return, in 1918, he worked as an artist during city holidays, and a stage set decorator in theaters. He became a professor at the Higher Art and Technical Workshops in 1921, and starting then he kept teaching throughout his entire life. Many artists during those years who studied painting in the capital studied together with him.

Like many artists of his generation who did not conform to official doctrine, Istomin’s name was not widely known. His memory has been preserved only owing to his students and friends, who preserved his artistic legacy, with people passing down his theoretical work from one person to another. For a long time, the name of Istomin remained unknown to the wider public. His first personal exhibition took place in 1961, and it had a great influence on artists, arousing the interest of art critics.

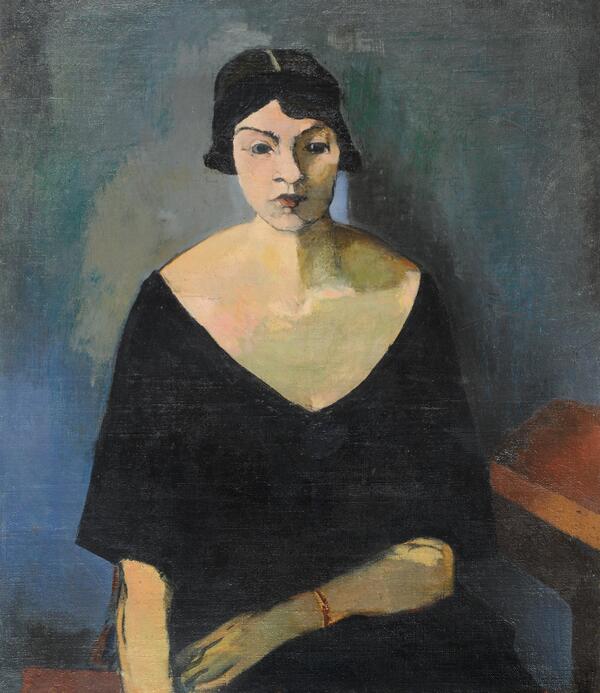

Istomin’s pivotal work is the painting Co-Eds (1933, State Tretyakov Gallery). Female Portrait, made in the early post-October Revolution period, interprets the experience that art has already been through. It shows a young woman seated against a wall. One hand of the model lies in her lap, while the other is lowered down. In the portrait, one can clearly feel the closeness to the physical principles of painting by André Derain, the French fauvist artist. But, for all the acuity inherent in his experiments with plasticity, Istomin remains faithful to the search for the spiritual and emotional components of the female image. The simple pose here is objective, typical, spatially meaningful, and rhythmically whole. The solemnity, and even a certain dramatic mood, is combined with an external stasis. The informative meaning of the portrait is determined chiefly by its color structure, the relationship of the black color of the dress silhouette with the contrastive illuminated face, neck, neckline, and arms. The color and sharp rhythm of the lines and angles here carry the main expressive load of the drama in the image, the self-awareness of the woman’s feelings.

Like many artists of his generation who did not conform to official doctrine, Istomin’s name was not widely known. His memory has been preserved only owing to his students and friends, who preserved his artistic legacy, with people passing down his theoretical work from one person to another. For a long time, the name of Istomin remained unknown to the wider public. His first personal exhibition took place in 1961, and it had a great influence on artists, arousing the interest of art critics.

Istomin’s pivotal work is the painting Co-Eds (1933, State Tretyakov Gallery). Female Portrait, made in the early post-October Revolution period, interprets the experience that art has already been through. It shows a young woman seated against a wall. One hand of the model lies in her lap, while the other is lowered down. In the portrait, one can clearly feel the closeness to the physical principles of painting by André Derain, the French fauvist artist. But, for all the acuity inherent in his experiments with plasticity, Istomin remains faithful to the search for the spiritual and emotional components of the female image. The simple pose here is objective, typical, spatially meaningful, and rhythmically whole. The solemnity, and even a certain dramatic mood, is combined with an external stasis. The informative meaning of the portrait is determined chiefly by its color structure, the relationship of the black color of the dress silhouette with the contrastive illuminated face, neck, neckline, and arms. The color and sharp rhythm of the lines and angles here carry the main expressive load of the drama in the image, the self-awareness of the woman’s feelings.

At the same time, relationships between the colors, and the rhythm of the composition of a solitary, seated figure, create the impression of a wavering chamber lyricism, on the verge of an unreal vision.