In 1825 the interregnum, one of the most difficult periods in history, began in the Russian Empire. On November 19, 1825, the childless emperor Alexander I died in Taganrog. According to the decree of Paul I on the succession to the throne, after Alexander’s death, the throne was to pass to the next in seniority — Konstantin. However, only a narrow circle of confidants knew that Konstantin Pavlovich had long abdicated the throne, referring to his secret unequal marriage with the Polish Countess Grudzinskaya.

On November 27, 1825, the population of St. Petersburg, and then Moscow, swore allegiance to Konstantin Pavlovich, even though an official manifesto on accession to the throne did not appear. At the same time, Konstantin did not accept the throne, but did not formally renounce it either. The state of uncertainty lasted until December 14, when, after Konstantin’s repeated renunciation of the throne, the Senate recognized the rights to the throne of Nikolai Pavlovich.

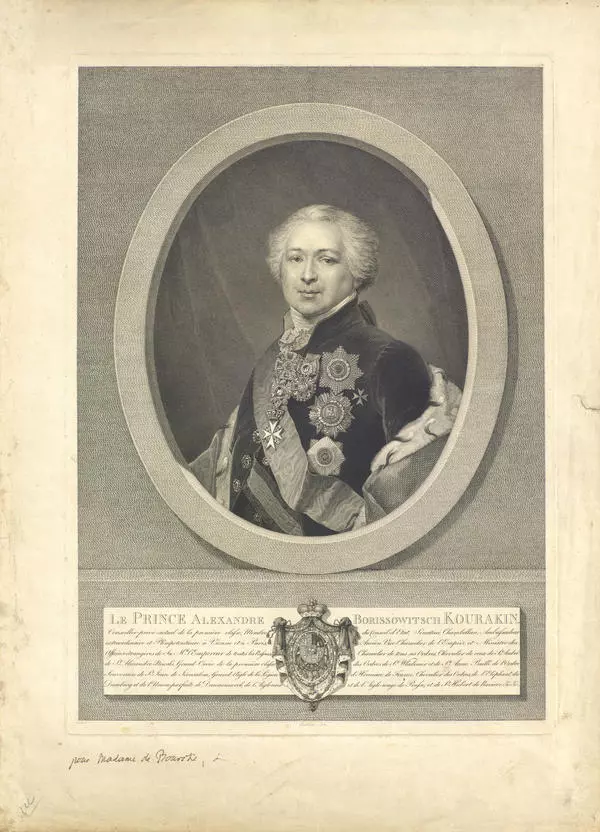

However, for more than two weeks, Konstantin formally was the emperor of Russia. Thence, in December 1825, sample rubles with the profile of the new emperor began to be coined at the mint, printing houses started printing portraits of Emperor Konstantin, as well as orders, passports and other state documents with printed headings ‘… by decree of Emperor Konstantin Pavlovich.’ This period of uncertainty was used by the Decembrists to speak at Senate Square.

Konstantin himself was in Warsaw all that time and came to St. Petersburg only for the coronation of Nicholas I. Two days before this event, Konstantin Pavlovich paid a visit to Kutuzov’s daughter, Elizaveta Mikhailovna. In the house of her husband, Major General Khitrovo, he saw his portrait as emperor and tore it apart. Some of the guests, apparently realizing the historical value of this document, picked up the scraps, glued them together and provided them with an explanatory inscription: “1826, August 20, at six o”clock in the afternoon, this portrait was torn apart by the Tsarevich himself in the Moscow house of Major General N.Z. Khitrovo, when His Imperial Highness visited the daughter of the Most Serene Prince. "

The portrait of Konstantin Pavlovich was made in the technique of lithography. The principle of operation lies in the name — from Greek it translates ‘I draw on a stone’. On a carefully polished stone of a special type of limestone, an image is drawn — with a special bold pencil, pen or brush. Then oily typographic ink, which is fixed only in the drawing, is applied to the moistened stone.

After that, the stone is fixed in the machine and a stamp is made.

From the first quarter of the 19th century, lithography conquered the book market and the field of printed graphics. In consequence of the ease of drawing it began to be widely used for printing posters, fancy pictures, illustrations, leaflets.

On November 27, 1825, the population of St. Petersburg, and then Moscow, swore allegiance to Konstantin Pavlovich, even though an official manifesto on accession to the throne did not appear. At the same time, Konstantin did not accept the throne, but did not formally renounce it either. The state of uncertainty lasted until December 14, when, after Konstantin’s repeated renunciation of the throne, the Senate recognized the rights to the throne of Nikolai Pavlovich.

However, for more than two weeks, Konstantin formally was the emperor of Russia. Thence, in December 1825, sample rubles with the profile of the new emperor began to be coined at the mint, printing houses started printing portraits of Emperor Konstantin, as well as orders, passports and other state documents with printed headings ‘… by decree of Emperor Konstantin Pavlovich.’ This period of uncertainty was used by the Decembrists to speak at Senate Square.

Konstantin himself was in Warsaw all that time and came to St. Petersburg only for the coronation of Nicholas I. Two days before this event, Konstantin Pavlovich paid a visit to Kutuzov’s daughter, Elizaveta Mikhailovna. In the house of her husband, Major General Khitrovo, he saw his portrait as emperor and tore it apart. Some of the guests, apparently realizing the historical value of this document, picked up the scraps, glued them together and provided them with an explanatory inscription: “1826, August 20, at six o”clock in the afternoon, this portrait was torn apart by the Tsarevich himself in the Moscow house of Major General N.Z. Khitrovo, when His Imperial Highness visited the daughter of the Most Serene Prince. "

The portrait of Konstantin Pavlovich was made in the technique of lithography. The principle of operation lies in the name — from Greek it translates ‘I draw on a stone’. On a carefully polished stone of a special type of limestone, an image is drawn — with a special bold pencil, pen or brush. Then oily typographic ink, which is fixed only in the drawing, is applied to the moistened stone.

After that, the stone is fixed in the machine and a stamp is made.

From the first quarter of the 19th century, lithography conquered the book market and the field of printed graphics. In consequence of the ease of drawing it began to be widely used for printing posters, fancy pictures, illustrations, leaflets.