Foolishness for Christ refers to giving up one’s worldly possessions and pretending to be crazy. This behavior was considered a spiritual and ascetic feat. The so-called holy fools behaved this way in order to achieve humility. They led such an extravagant lifestyle because they strove to avoid the sin of pride which was recognized as the root of all sins.

Holy fools pretended to be crazy and were often ridiculed, scorned, or even beaten by the crowd. In this allegorical symbolic way, they denounced evil both in word and action.

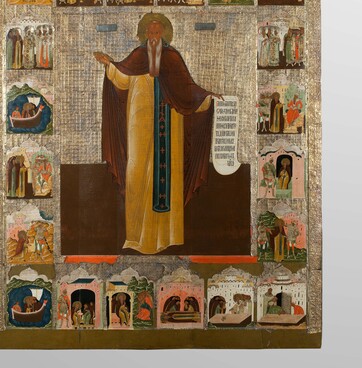

It is believed that most of the holy fools had the gift of prophecy. The feat of being a fool for Christ’s sake was especially widespread in Russia. One of the Russian holy fools was Isidore of Rostov depicted by a 17th-century painter in this icon. Legend has it that Isidore moved to Russia from one of the “Latin” countries in Western Europe. However, his exact country of origin is unknown.

His parents were of noble origin and Catholic faith. As a young man, Isidore became fascinated with Orthodox Christianity. Isidore left his country, passed through many towns and villages, and arrived in the glorious and crowded city of Rostov where he converted to Orthodoxy.

The holy fool built himself a crude, roofless hut of brushwood on a dry piece of land in the middle of a swampy pool. During the day, he would go out into the city streets where many citizens took him for a madman, insulted and offended him. Isidore remembered the agony of Jesus Christ on the cross and endured all the insults humbly. He prayed to God silently, asking Him to forgive the tormentors for their sins.

Many Christians believed that he was a man of God, and he helped them with advice and predictions. For possessing the gift of prophecy and making accurate predictions, Isidore was nicknamed Tverdislov (“Constant of Word”) meaning that his words were “constant”.

According to manuscripts

of the 17th –19th centuries, the saint came to Rostov in

1419 and died either in 1474 or 1484. Isidore of Rostov was officially

canonized in the second half of the 16th century when he had been

already venerated as a saint for a long time.