The 19th and early 20th centuries were the heyday of Russian glassmaking. Dynasties of talented craftsmen were working at glass factories. The artisans were carefully preserving the experience of their predecessors and improving their skills and style.

Traditionally, factories produced household glassware, mainly dishes, and expensive crystal items with rich decor for noble customers. “Fun” products stood somewhat apart — these were all kinds of vessels with secrets: “bottomless” jugs, “singing” vessels, glasses with cross sections and decanters with figures inside.

The same technology was used to put figures of birds, fish, fruit or flowers inside a decanter with a narrow neck. Devils and pigs were put in vessels for strong drinks that were consumed at lively parties. The figures reminded about the Russian sayings about drinking: “to get drunk to hell” or “to get drunk as a pig”.

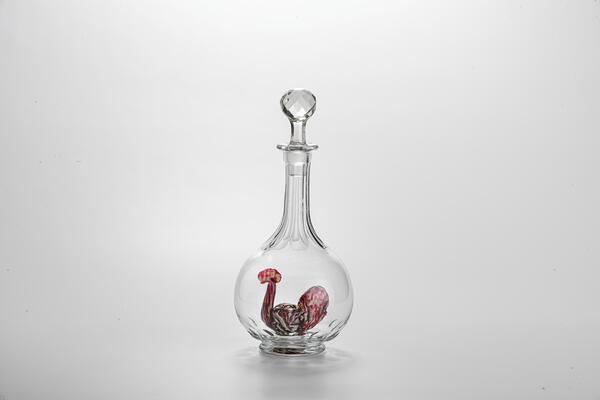

According to the price lists of that time, decanters with pigs and cockerels were made at the Nikolsko-Bakhmetevsky factory. Cockerels were especially popular. In Russian folklore, this bird is one of the most common and at the same time ambiguous characters. The cockerel can be sublime or conceited, brave and clever or frivolous and cowardly, but usually self-assured. As a “solar” bird, it often symbolizes buoyancy and awakening, good luck and wealth. When put in the decanter, a cockerel probably illustrated the sayings “to walk like a rooster” (to put on airs) and “to behave like a rooster” (to be peppy, to behave like a bully).

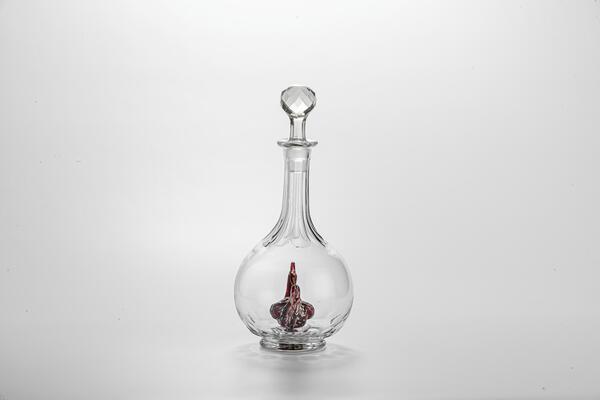

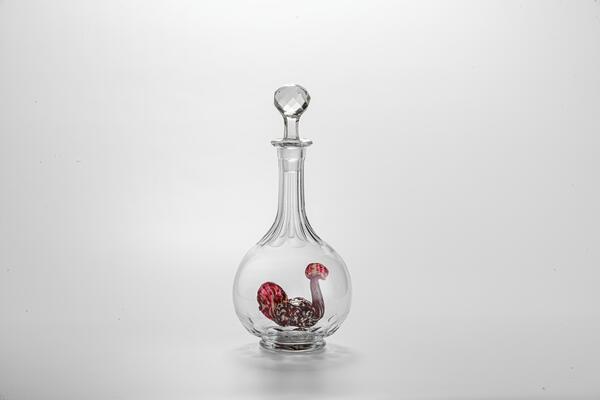

The craftsmen from the Nikolsko-Bakhmetevsky factory placed the bird in a decanter of colorless glass with a spherical body. This form allowed not only a good view of the figure.

When the decanter was filled with liquid, the figurine looked almost double its size. The spherical shape of the vessel enhanced the effect. When the decanter became empty, the cockerel got small again.

The manufacturing of such a “surprise” object, which was used at the Nikolsko-Bakhmetevsky factory, seemed simple, but only highly professional artisans could employ this technique. Two glass blowers were working simultaneously: one made a cockerel, the other blew out the blank of a decanter and cut off its top. The first craftsman put the hot cockerel he had made on the bottom of the vessel, and his colleague immediately pulled out the throat of the decanter.

Traditionally, factories produced household glassware, mainly dishes, and expensive crystal items with rich decor for noble customers. “Fun” products stood somewhat apart — these were all kinds of vessels with secrets: “bottomless” jugs, “singing” vessels, glasses with cross sections and decanters with figures inside.

The same technology was used to put figures of birds, fish, fruit or flowers inside a decanter with a narrow neck. Devils and pigs were put in vessels for strong drinks that were consumed at lively parties. The figures reminded about the Russian sayings about drinking: “to get drunk to hell” or “to get drunk as a pig”.

According to the price lists of that time, decanters with pigs and cockerels were made at the Nikolsko-Bakhmetevsky factory. Cockerels were especially popular. In Russian folklore, this bird is one of the most common and at the same time ambiguous characters. The cockerel can be sublime or conceited, brave and clever or frivolous and cowardly, but usually self-assured. As a “solar” bird, it often symbolizes buoyancy and awakening, good luck and wealth. When put in the decanter, a cockerel probably illustrated the sayings “to walk like a rooster” (to put on airs) and “to behave like a rooster” (to be peppy, to behave like a bully).

The craftsmen from the Nikolsko-Bakhmetevsky factory placed the bird in a decanter of colorless glass with a spherical body. This form allowed not only a good view of the figure.

When the decanter was filled with liquid, the figurine looked almost double its size. The spherical shape of the vessel enhanced the effect. When the decanter became empty, the cockerel got small again.

The manufacturing of such a “surprise” object, which was used at the Nikolsko-Bakhmetevsky factory, seemed simple, but only highly professional artisans could employ this technique. Two glass blowers were working simultaneously: one made a cockerel, the other blew out the blank of a decanter and cut off its top. The first craftsman put the hot cockerel he had made on the bottom of the vessel, and his colleague immediately pulled out the throat of the decanter.