Trilobites are the class of ancient marine arthropods that included several thousand different species. The Welsh scientist Edward Lhuyd first described them as Trinucleus in 1698. The German naturalist Johann Ernst Immanuel Walch gave to these creatures a modern name, which means ‘three-sided’.

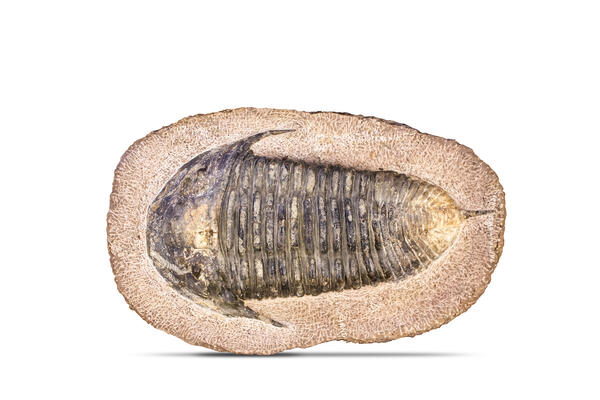

Different types of trilobites could reach 70 — 90 centimeters in length. Their body consisted of a head covered with a protective shell, a trunk of several segments, and a tail. Scientists suggest that the head of these creatures consisted not only of the brain but also other organs — the heart and stomach. The limbs performed several functions at once: they crushed food, helped to breathe and move.

The trilobites had complicated compound eyes, which consisted of several fragments similar to a grid. In those species that burrowed into the sea mud, the eyes were located on stalks, which is similar to some modern crustaceans. Instead of a protein lens, trilobites had mineral calcite lenses inside the eyeball. Nowadays, such structure exists only among chiton mollusks and representatives of the echinoderm type — brittle star. The agnostid trilobites had no eyes at all: perhaps this was due to life in deep waters with a lack of light.

These creatures moved in different ways. Some species could swim well while others crawled along the bottom and buried themselves in sand or silt. Their diet was also diverse. It included fragments of marine plants, plankton, and small invertebrates.

The trilobites were probably digeneous. Each individual combined male and female characteristics. They laid eggs, from which larvae emerged and developed into adult species. As they grew, these arthropods molted and shed their shells — these are what modern paleontologists often find in ancient fossils. After each molt, the new trilobite shell lengthened by several segments.

In case of danger, some species of trilobites could curl up into a ball so that a strong shell protected the soft abdomen.

Different types of trilobites could reach 70 — 90 centimeters in length. Their body consisted of a head covered with a protective shell, a trunk of several segments, and a tail. Scientists suggest that the head of these creatures consisted not only of the brain but also other organs — the heart and stomach. The limbs performed several functions at once: they crushed food, helped to breathe and move.

The trilobites had complicated compound eyes, which consisted of several fragments similar to a grid. In those species that burrowed into the sea mud, the eyes were located on stalks, which is similar to some modern crustaceans. Instead of a protein lens, trilobites had mineral calcite lenses inside the eyeball. Nowadays, such structure exists only among chiton mollusks and representatives of the echinoderm type — brittle star. The agnostid trilobites had no eyes at all: perhaps this was due to life in deep waters with a lack of light.

These creatures moved in different ways. Some species could swim well while others crawled along the bottom and buried themselves in sand or silt. Their diet was also diverse. It included fragments of marine plants, plankton, and small invertebrates.

The trilobites were probably digeneous. Each individual combined male and female characteristics. They laid eggs, from which larvae emerged and developed into adult species. As they grew, these arthropods molted and shed their shells — these are what modern paleontologists often find in ancient fossils. After each molt, the new trilobite shell lengthened by several segments.

In case of danger, some species of trilobites could curl up into a ball so that a strong shell protected the soft abdomen.