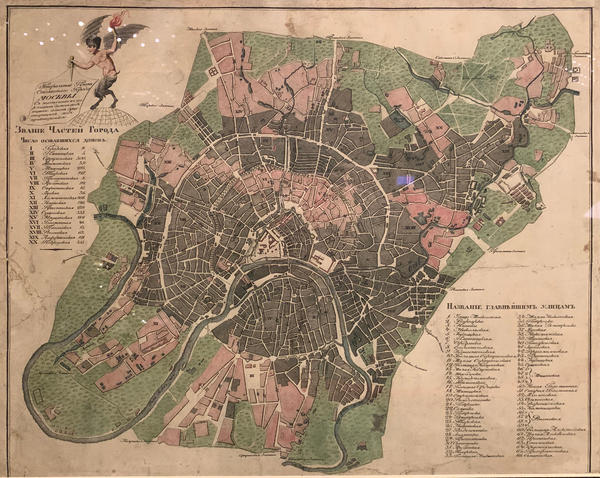

You are looking at the Master Plan of Moscow showing comprehensively the capital’s losses after the fire of 1812. For the first time the document was issued in April 1813 in the Moscow printing house of Semyon Selivanovsky as an annex to the book The Russians and Napoleon Bonaparte. Museum researchers attribute the book authorship to Alexander Yakovlevich Bulgakov who at that time served under Count Fyodor Rastopchin, Moscow Commander-in-Chief. It is not known who drew the plan.

In September 1812, French troops entered the capital of the Russian empire. For a whole month, Moscow was occupied by Napoleon until early October when the emperor realized the futility of a further stay in the city and gave the order to retreat. The position of the occupation troops was unenviable: before withdrawal of the Russian army from the city, a tacit order was given to destroy all that could directly or indirectly maintain the stay of Frenchmen in Moscow.

During the month, power magazines were exploding, warehouses with property, barques with grain and animal fodder were burning. To prevent the Frenchmen from extinguishing the fires quickly, fire-fighting squads had been taken out of the city along with the equipment and gear. The situation was aggravated by the dry and windy weather which contributed to the fire spread to the adjacent buildings. While the active phase of calamity lasted five days only, small local fires continued to burn until the end of September.

The great fire destroyed about 70% of buildings in the city and caused material losses the amount of which could be compared with the annual budget of the whole empire of that period. After the war was over, the city authorities took up restoration of the capital. For a start, a long detailed list of churches, monasteries, cathedrals, residential houses and government buildings that survived the fires was made. Then, based on the data received, a map of Moscow was made with detailed indication of the burnt houses designated with oblique hatching, and of the buildings that remained intact shown with a dotted line.

The Master Plan was signed by the Moscow governmental land-surveyor court councilor Fillin. The document dressed with rich binding, embossed with morocco leather and gold was kept in the office of the Moscow Governor-General until 1917. After the October revolution, it was first kept in the Old Moscow museum and later was transferred to the Historical Museum.

In September 1812, French troops entered the capital of the Russian empire. For a whole month, Moscow was occupied by Napoleon until early October when the emperor realized the futility of a further stay in the city and gave the order to retreat. The position of the occupation troops was unenviable: before withdrawal of the Russian army from the city, a tacit order was given to destroy all that could directly or indirectly maintain the stay of Frenchmen in Moscow.

During the month, power magazines were exploding, warehouses with property, barques with grain and animal fodder were burning. To prevent the Frenchmen from extinguishing the fires quickly, fire-fighting squads had been taken out of the city along with the equipment and gear. The situation was aggravated by the dry and windy weather which contributed to the fire spread to the adjacent buildings. While the active phase of calamity lasted five days only, small local fires continued to burn until the end of September.

The great fire destroyed about 70% of buildings in the city and caused material losses the amount of which could be compared with the annual budget of the whole empire of that period. After the war was over, the city authorities took up restoration of the capital. For a start, a long detailed list of churches, monasteries, cathedrals, residential houses and government buildings that survived the fires was made. Then, based on the data received, a map of Moscow was made with detailed indication of the burnt houses designated with oblique hatching, and of the buildings that remained intact shown with a dotted line.

The Master Plan was signed by the Moscow governmental land-surveyor court councilor Fillin. The document dressed with rich binding, embossed with morocco leather and gold was kept in the office of the Moscow Governor-General until 1917. After the October revolution, it was first kept in the Old Moscow museum and later was transferred to the Historical Museum.