“Slava Sevastopolya” is the oldest city newspaper, published since December 19, 1917.

Throughout its existence, it has changed its name more than once. In 1917–1918, the publication was issued under the title “News of the Sevastopol Military Revolutionary Committee”, then as “News of the Sevastopol Revolutionary Committee and the Sevastopol Soviet”. In November 1920, the name was changed to “Bulletin of the Sevastopol Military Revolutionary Committee”, and from December 2, 1920, the newspaper was renamed to “Mayak Communy”.

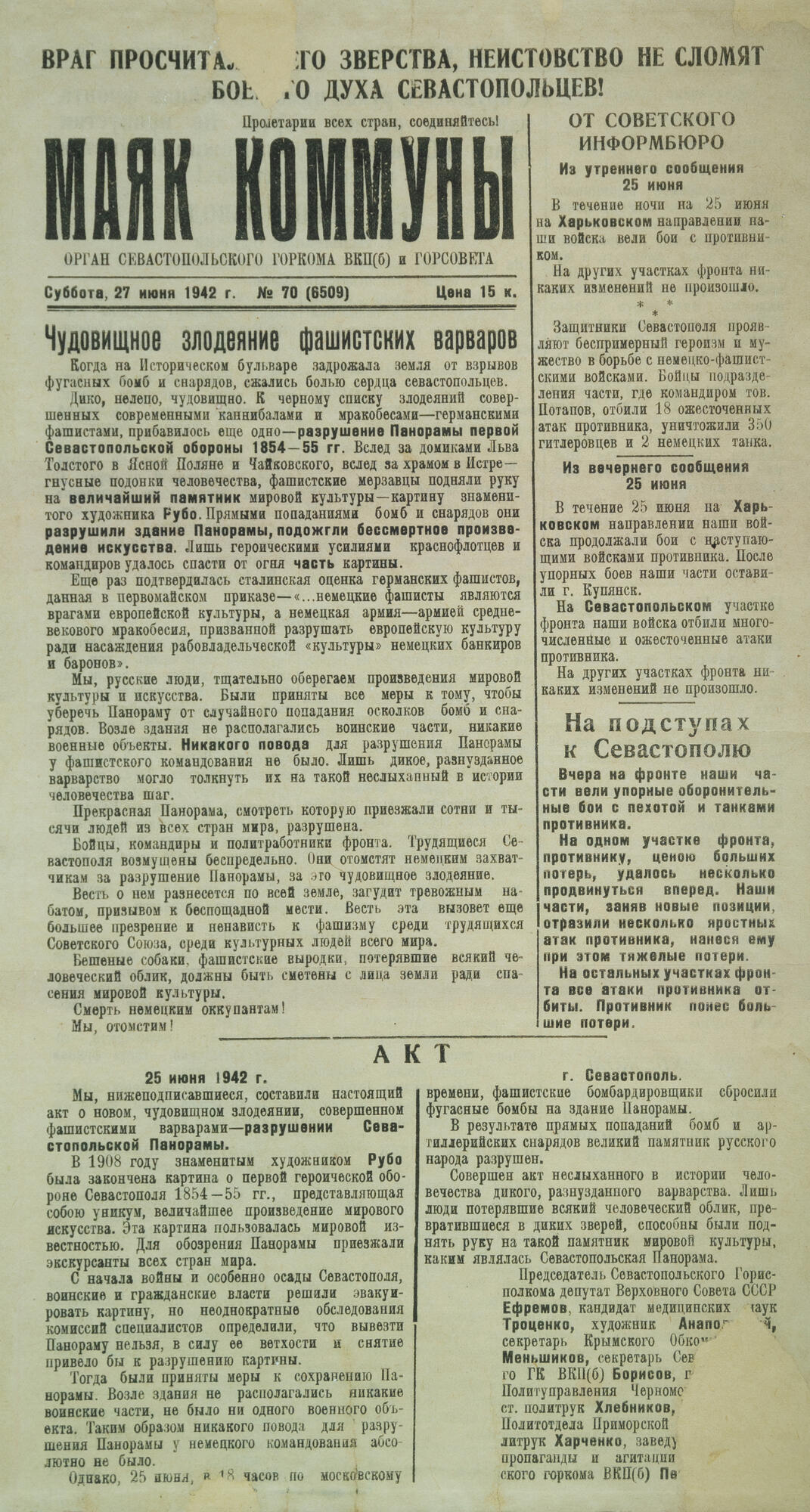

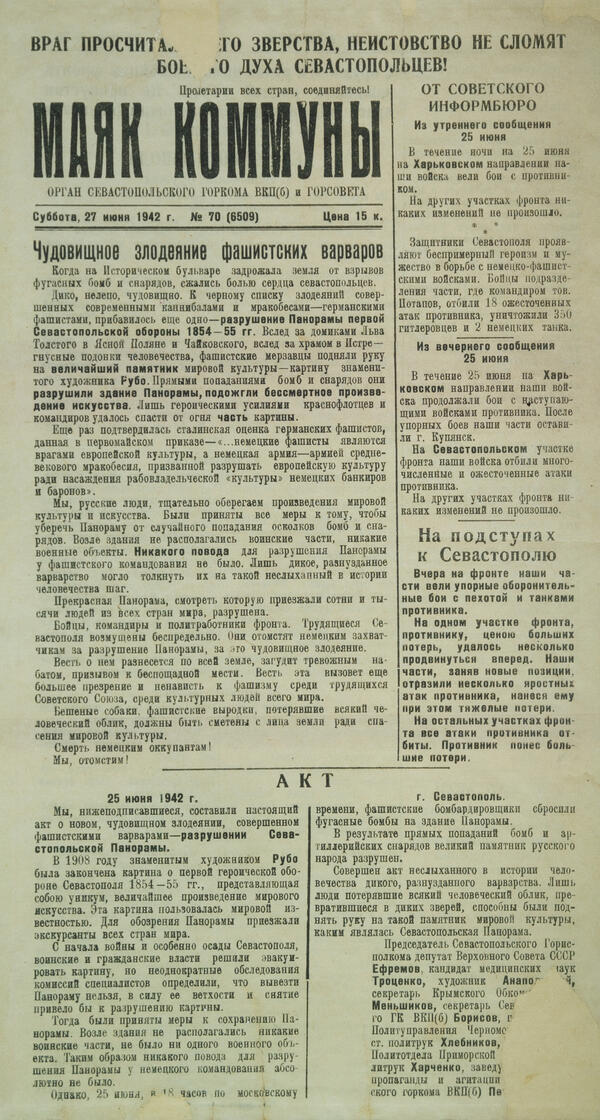

The museum’s exhibition presents “Mayak Communy” of June 27, 1942 — this name was used for one of the last issues of the publication right before the occupation of the city during the Great Patriotic War.

The defense of Sevastopol lasted from October 30, 1941 to July 4, 1942, during which time the newspaper reported on how hard and bravely the residents and Soviet soldiers fought for the city.

The most difficult times for the newspaper came in May — June 1942. On May 31, the newspaper did not come out: one of the big bombs hit the building of the printing house. Some workers were killed and some seriously injured. The workshops, as well as the premises where the editorial office was located, were destroyed, the paper stock burned. The journalists moved to the underground cinema “Udarnik”.

On June 2, the newspaper was published, but the circulation was reduced to 800 copies. Journalist Vladimir Aposhansky described what efforts it cost in his front-line notebook, “The raid has just ended. The ruins of the Udarnik cinema were still smoking <…> The building of the editorial office, burned down during the night, still smelled of heat. The typesetters and print workers were waiting for the editor. He stepped up to the workers and said: ‘Comrades! Sevastopol lives, and the newspaper must be published. We must clear the entrance to the printing office.’ These words were enough for people, burning to blisters and panting with smoke, to start pulling apart the hot beams and rafters. In the evening, typesetters and imposers entered the red-hot basement <…> and in the morning the Sevastopol residents, unaware of the agony in which their own newspaper was born, read the latest issue of the Mayak Communy.”

On June 7, the Nazis launched a third general offensive against the city. In those days, the newspaper was published under the slogans: “More courage and perseverance! Stronger rebuff for the enemy!”, “All forces — to defeat the enemy! The people of Sevastopol do not give up!”

On June 25, the Germans entered the upper reaches of Sevastopol Bay. And on June 27, the front page featured an article “The monstrous atrocity of the fascist barbarians”. The publication said that at 6.40 p.m., June 25, 1942, the enemies dropped bombs on the building of the Panorama Museum dedicated to the first defense of Sevastopol. The painting was set on fire. The sailor cadets rushed to the burning building. Although burning themselves, they cut the canvas into pieces and carried it out of the fire in chain order. They had to stop when the dome of the building collapsed.

The last issue of the newspaper during the defense period appeared on June 29, 1942, and the next day the enemy came close to the city. The next issue would not be around until 1944.

Throughout its existence, it has changed its name more than once. In 1917–1918, the publication was issued under the title “News of the Sevastopol Military Revolutionary Committee”, then as “News of the Sevastopol Revolutionary Committee and the Sevastopol Soviet”. In November 1920, the name was changed to “Bulletin of the Sevastopol Military Revolutionary Committee”, and from December 2, 1920, the newspaper was renamed to “Mayak Communy”.

The museum’s exhibition presents “Mayak Communy” of June 27, 1942 — this name was used for one of the last issues of the publication right before the occupation of the city during the Great Patriotic War.

The defense of Sevastopol lasted from October 30, 1941 to July 4, 1942, during which time the newspaper reported on how hard and bravely the residents and Soviet soldiers fought for the city.

The most difficult times for the newspaper came in May — June 1942. On May 31, the newspaper did not come out: one of the big bombs hit the building of the printing house. Some workers were killed and some seriously injured. The workshops, as well as the premises where the editorial office was located, were destroyed, the paper stock burned. The journalists moved to the underground cinema “Udarnik”.

On June 2, the newspaper was published, but the circulation was reduced to 800 copies. Journalist Vladimir Aposhansky described what efforts it cost in his front-line notebook, “The raid has just ended. The ruins of the Udarnik cinema were still smoking <…> The building of the editorial office, burned down during the night, still smelled of heat. The typesetters and print workers were waiting for the editor. He stepped up to the workers and said: ‘Comrades! Sevastopol lives, and the newspaper must be published. We must clear the entrance to the printing office.’ These words were enough for people, burning to blisters and panting with smoke, to start pulling apart the hot beams and rafters. In the evening, typesetters and imposers entered the red-hot basement <…> and in the morning the Sevastopol residents, unaware of the agony in which their own newspaper was born, read the latest issue of the Mayak Communy.”

On June 7, the Nazis launched a third general offensive against the city. In those days, the newspaper was published under the slogans: “More courage and perseverance! Stronger rebuff for the enemy!”, “All forces — to defeat the enemy! The people of Sevastopol do not give up!”

On June 25, the Germans entered the upper reaches of Sevastopol Bay. And on June 27, the front page featured an article “The monstrous atrocity of the fascist barbarians”. The publication said that at 6.40 p.m., June 25, 1942, the enemies dropped bombs on the building of the Panorama Museum dedicated to the first defense of Sevastopol. The painting was set on fire. The sailor cadets rushed to the burning building. Although burning themselves, they cut the canvas into pieces and carried it out of the fire in chain order. They had to stop when the dome of the building collapsed.

The last issue of the newspaper during the defense period appeared on June 29, 1942, and the next day the enemy came close to the city. The next issue would not be around until 1944.