In the 19th century, metal, glass, paper, and other materials were used as the basis for photographic prints. One of the most common photographic techniques of the past was a ferrotype — a photograph on an iron plate. It was quick and easy to create; the affordable price was another of its advantages. The technology was originally known as melainotype.

The ferrotype process was patented in 1856 by an American called Hamilton Smith. To make a ferrotype, polished iron plates coated with a light-sensitive collodion layer were used. It took only a few minutes to create a ferrotype, and the process did not involve the negative stage. A reversed positive image was immediately produced in a single copy. Its surface was lacquered to prevent any damage. Sometimes ferrotypes were colored. They did not require the same lighting for viewing as daguerreotypes, were easier to make, and were more durable.

Another form of the technology was called a tintype — a print on a tin plate. Tintypes became incredibly widespread in the United States, whereas in Russia and Europe it was ferrotypes that were popular.

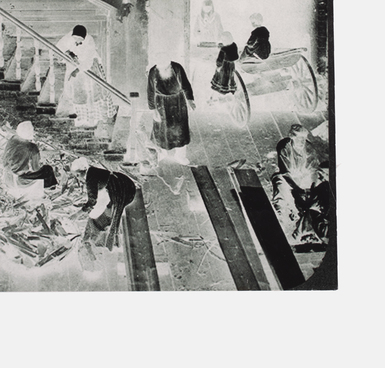

Ferrotyping was initially intended as a type of indoor photography, a cheap alternative to more complicated and expensive photographic processes of daguerreotype and ambrotype. It was adopted fairly quickly by itinerant photographers. Ferrotypes were made in large quantities at fairs, festivals and resorts. Special cameras were designed for them, equipped with a container for rapid chemical treatment. Ferrotypes were usually made on metal plates of several sizes. But most often the size of the plates matched that of the cassette inserted into the camera. Special photo albums with windows were made for the smallest ferrotypes. As ferrotypes were lightweight and unbreakable, they could even be mailed.

The first ferrotypes came in expensive frames, just like daguerreotypes. In 1863, an expensive cardboard vignette frame with an oval-shaped window and a decorative border, was designed for ferrotypes. The vignette was popular for only a few years. Later, ferrotypes featured no special decoration, which accelerated and considerably reduced the cost of the process. By the end of the 19th century, ferrotypes had been superseded by more modern technologies, but they were still used in some places up to World War I.