In the collection of the museum, there are cross-sections of various trees: amur corktree, hornbeam, spruce, birch, fir, boxwood, and others.

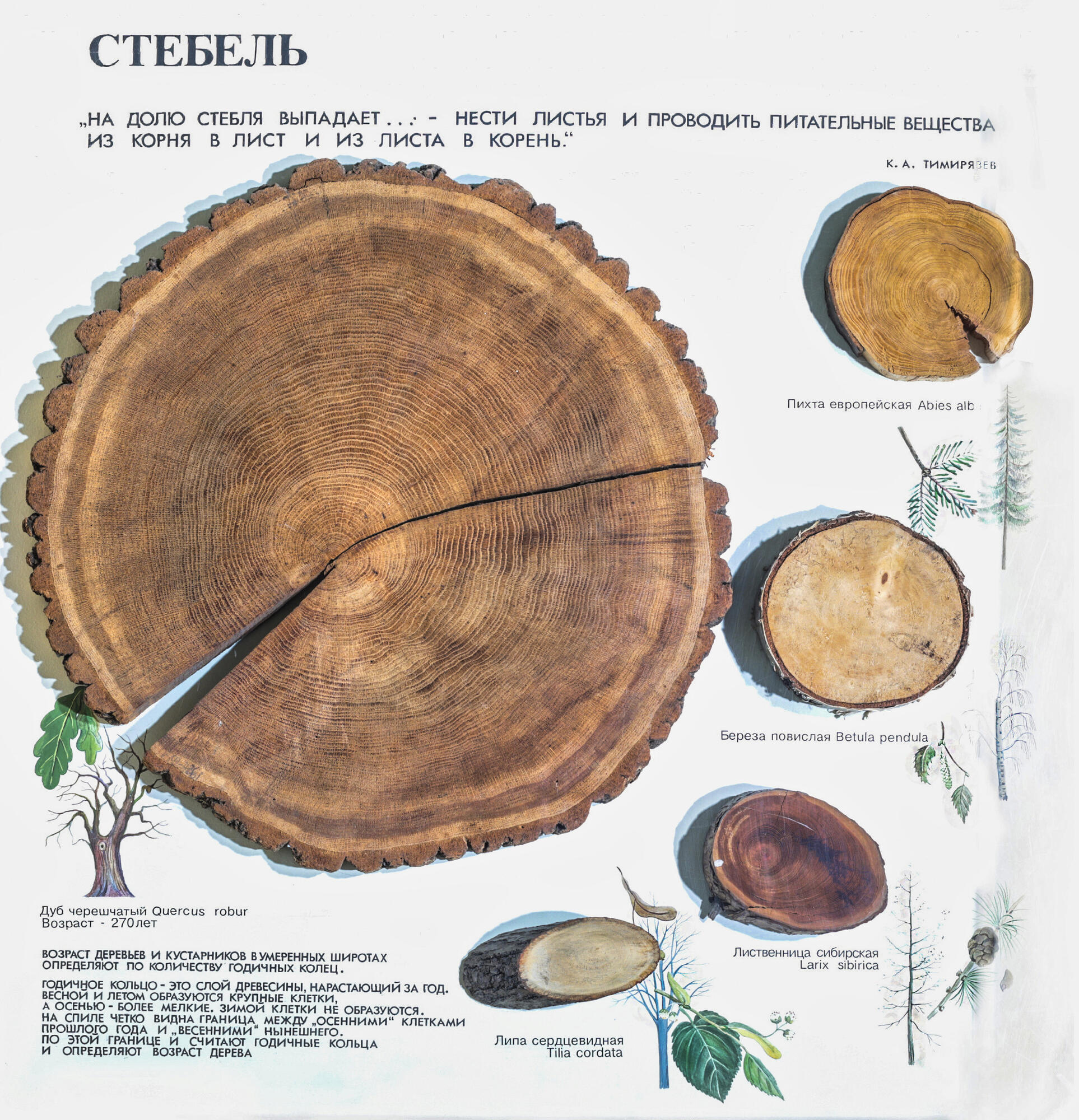

One of the most interesting exhibit items is a cross-sectional cut of English oak (Quercus robur) that is on display in the ‘Plant Life’ hall. This item came to the museum from the ‘Forestry’ pavilion at the Exhibition of Achievements of National Economy of the USSR in 1965. At the time the tree was cut down it was 270 years old.

You can determine the exact age of a tree by counting the annual rings on the trunk cut. They form only in trees growing in seasonal climates (areas where the seasons change).

Between the wood and the bark, trees have a thin layer of meristem called cambium. It forms the cells of the wood and bark each year. Through the wood vessels, water and minerals move up from the roots to the top of the trunk. This is called upward flow.

In early spring the cambium forms wood vessels with a wide diameter. This way the upward current can actively supply the growing tree with the necessary substances. These large vessels form the inner part of the annual ring. In autumn, when the growth processes stop, the cambium creates narrow-lumen vessels with thick walls, as the intensity of water supply to the tree decreases. The main function of these cells, which form the outer layer of the annual ring, is to give strength to the trunk. The next year this cycle repeats.

Hence wood cell layers with wide and narrow gap interchange, and it is possible to determine visually the border between cells of two nearest years of growing.

This method of calculating a tree’s age sometimes gives a slight error. When the foliage dies off in the spring, for example, because of spring frosts or if pests have undermined the tree, two narrow rings may form during the season. Rings may also fail to form at all if there is heavy spring pruning. However, such phenomena are rare as scientists say.

Thanks to a cross-sectional cut or control cylinders taken from a living tree with a special drill, we can tell the story of the tree’s life: in what climatic conditions it grew up or whether it had neighbors nearby. This is the science of dendroclimatology. A tree growing in perfect light, in abundant rainfall, in the absence of oppression from neighboring trees forms wide rings. A tree growing under the forest canopy with little water and rains and damaged by insects will form narrow annual rings.

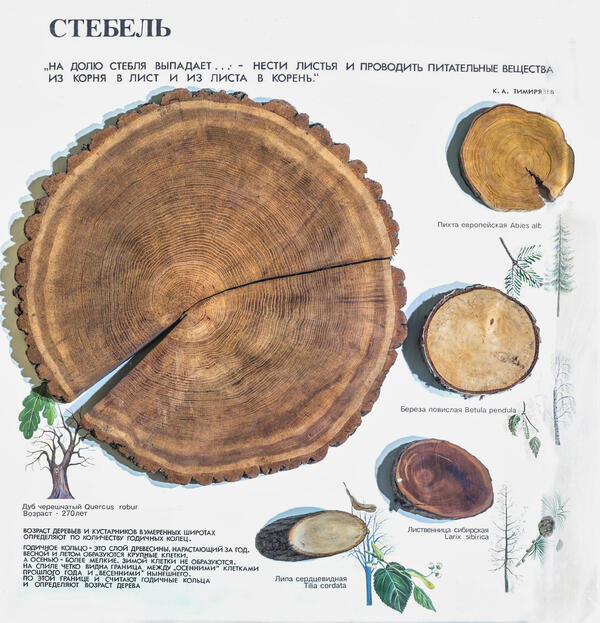

One of the most interesting exhibit items is a cross-sectional cut of English oak (Quercus robur) that is on display in the ‘Plant Life’ hall. This item came to the museum from the ‘Forestry’ pavilion at the Exhibition of Achievements of National Economy of the USSR in 1965. At the time the tree was cut down it was 270 years old.

You can determine the exact age of a tree by counting the annual rings on the trunk cut. They form only in trees growing in seasonal climates (areas where the seasons change).

Between the wood and the bark, trees have a thin layer of meristem called cambium. It forms the cells of the wood and bark each year. Through the wood vessels, water and minerals move up from the roots to the top of the trunk. This is called upward flow.

In early spring the cambium forms wood vessels with a wide diameter. This way the upward current can actively supply the growing tree with the necessary substances. These large vessels form the inner part of the annual ring. In autumn, when the growth processes stop, the cambium creates narrow-lumen vessels with thick walls, as the intensity of water supply to the tree decreases. The main function of these cells, which form the outer layer of the annual ring, is to give strength to the trunk. The next year this cycle repeats.

Hence wood cell layers with wide and narrow gap interchange, and it is possible to determine visually the border between cells of two nearest years of growing.

This method of calculating a tree’s age sometimes gives a slight error. When the foliage dies off in the spring, for example, because of spring frosts or if pests have undermined the tree, two narrow rings may form during the season. Rings may also fail to form at all if there is heavy spring pruning. However, such phenomena are rare as scientists say.

Thanks to a cross-sectional cut or control cylinders taken from a living tree with a special drill, we can tell the story of the tree’s life: in what climatic conditions it grew up or whether it had neighbors nearby. This is the science of dendroclimatology. A tree growing in perfect light, in abundant rainfall, in the absence of oppression from neighboring trees forms wide rings. A tree growing under the forest canopy with little water and rains and damaged by insects will form narrow annual rings.