Russia became concerned with issues of public schooling only in the early 19th century. A number of laws passed in the first three decades of the 19th century defined the structure of the educational system and ordered the creation of training schools in villages. In state-owned villages, it was the job of peasants to maintain them.

However, until the 1850s, schools were mostly opened in cities, funded by the city administrations. Children of merchants, artisans, and low-rank officials were eligible to attend them. Various ministries, including the Ministry of State Property, opened several schools, although their number was insignificant. In 1847, the Ministry of State Property opened a school in Bolshie Mytishchi and accommodated it in a rented farmhouse. Since there were not many students in such schools, the villages' literacy figures were low. For example, by the late 1860s, there were only 30 literate men in Mytishchi and not a single woman who could read or write. In all villages of the Mytishchi Volost (rural district) combined, one could find a total of 115 literate men and three literate women out of 2,500.

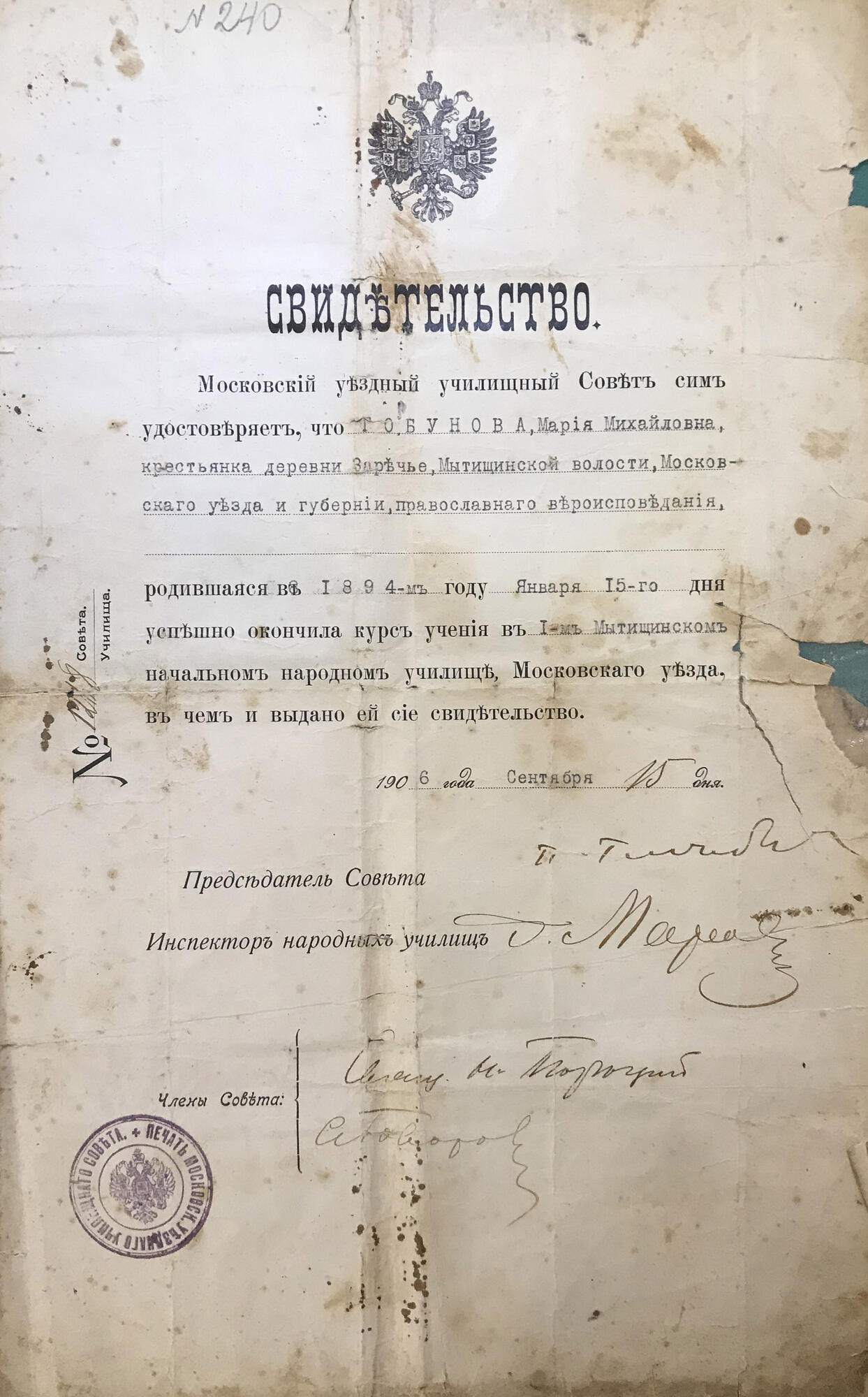

After the serfhood was abolished, the state started promoting education among villagers more actively. The first school in the Moscow Uyezd (administrative territorial unit) was opened in Bolshie Mytishchi in 1872, using the facilities of the school established by the Ministry of State Property. In 1875, 46 boys and five girls from this and nearby villages attended the school. A report written by a member of the uyezd school council says that students of the Mytishchi school ‘…can read proficiently and expressively… and make equally good progress in drawing and singing’.

Courses in district schools took three years. The 1879 Statute of Schools read: ‘Tuition is free. Boys from the age of nine and girls from the age of eight are eligible to attend. Classes start on September 15. Classes last from 9 in the morning until 3 in the afternoon with a lunch break. Corporal punishment is not allowed.’

In the early 20th century, the number of students in district schools kept growing, although not everyone attended classes regularly, especially children engaged in housework.

However, until the 1850s, schools were mostly opened in cities, funded by the city administrations. Children of merchants, artisans, and low-rank officials were eligible to attend them. Various ministries, including the Ministry of State Property, opened several schools, although their number was insignificant. In 1847, the Ministry of State Property opened a school in Bolshie Mytishchi and accommodated it in a rented farmhouse. Since there were not many students in such schools, the villages' literacy figures were low. For example, by the late 1860s, there were only 30 literate men in Mytishchi and not a single woman who could read or write. In all villages of the Mytishchi Volost (rural district) combined, one could find a total of 115 literate men and three literate women out of 2,500.

After the serfhood was abolished, the state started promoting education among villagers more actively. The first school in the Moscow Uyezd (administrative territorial unit) was opened in Bolshie Mytishchi in 1872, using the facilities of the school established by the Ministry of State Property. In 1875, 46 boys and five girls from this and nearby villages attended the school. A report written by a member of the uyezd school council says that students of the Mytishchi school ‘…can read proficiently and expressively… and make equally good progress in drawing and singing’.

Courses in district schools took three years. The 1879 Statute of Schools read: ‘Tuition is free. Boys from the age of nine and girls from the age of eight are eligible to attend. Classes start on September 15. Classes last from 9 in the morning until 3 in the afternoon with a lunch break. Corporal punishment is not allowed.’

In the early 20th century, the number of students in district schools kept growing, although not everyone attended classes regularly, especially children engaged in housework.