The painting “Sworn Enemy’s Dream” is one of Aslan Bugaev’s most recognizable works. The artist dedicated it to the ancient Caucasian custom of a blood feud. The killing of a member of one’s family was punishable by vengeance on the criminal and his family until the perpetrator died or his enemies were reconciled. Blood feud corresponded to the adats, a system of customs and traditions opposed to the official religious law, that is shariah.

The 19th-century researcher Leonty Lulie wrote, “Blood vengeance among the highlanders is not an unrestrained, irrepressible feeling, like the Corsican vendetta; it is rather an obligation imposed by honor, public opinion, the demand for blood for blood”. When the perpetrator of a crime was found, blood vengeance was declared to him through a respected intermediary: usually, the mullah or the village elder played this role. Close relatives of the killed were not present at the meeting of the intermediary with the guilty person. There were cases when it happened 50-100 years after the crime when the direct participants of events had not been alive for a long time. If sworn enemies died their own death and were not forgiven, revenge was taken on their sons, brothers or grandchildren.

By the turn of the 20th century, the mountain peoples came to the conclusion that the ancient custom did not solve conflicts between families, but only multiplied the number of crimes. Therefore, the killing of a sworn enemy was replaced by a monetary fine. However, Chechens and Terek Nogais refused to accept such payments and said that they “do not trade in the blood of the murdered man”.

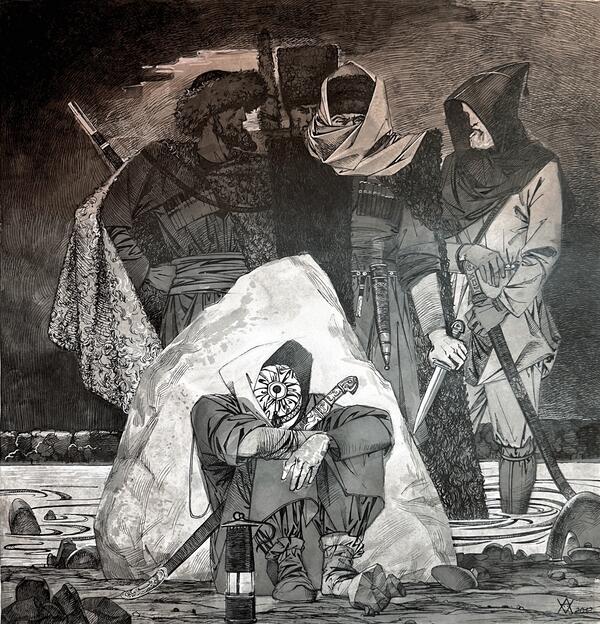

Aslan Bugaev’s painting shows a sleeping man in Chechen national clothes in the foreground. He leans against a large boulder with his back, holding a naked sword to his knees, and a burning lantern stands at his feet. Seated behind the boulder are four more men in traditional costumes: these are the sleeping man’s blood enemies. The face of one of them is covered by a white cloth, and he clutches a naked sword with his hand. The features of the two men behind this character are not depicted in detail: they resemble silhouettes against a crimson and black background. The head of the man on the right is covered by a pointed hood, its edge also obscures part of his face.

The 19th-century researcher Leonty Lulie wrote, “Blood vengeance among the highlanders is not an unrestrained, irrepressible feeling, like the Corsican vendetta; it is rather an obligation imposed by honor, public opinion, the demand for blood for blood”. When the perpetrator of a crime was found, blood vengeance was declared to him through a respected intermediary: usually, the mullah or the village elder played this role. Close relatives of the killed were not present at the meeting of the intermediary with the guilty person. There were cases when it happened 50-100 years after the crime when the direct participants of events had not been alive for a long time. If sworn enemies died their own death and were not forgiven, revenge was taken on their sons, brothers or grandchildren.

By the turn of the 20th century, the mountain peoples came to the conclusion that the ancient custom did not solve conflicts between families, but only multiplied the number of crimes. Therefore, the killing of a sworn enemy was replaced by a monetary fine. However, Chechens and Terek Nogais refused to accept such payments and said that they “do not trade in the blood of the murdered man”.

Aslan Bugaev’s painting shows a sleeping man in Chechen national clothes in the foreground. He leans against a large boulder with his back, holding a naked sword to his knees, and a burning lantern stands at his feet. Seated behind the boulder are four more men in traditional costumes: these are the sleeping man’s blood enemies. The face of one of them is covered by a white cloth, and he clutches a naked sword with his hand. The features of the two men behind this character are not depicted in detail: they resemble silhouettes against a crimson and black background. The head of the man on the right is covered by a pointed hood, its edge also obscures part of his face.