The Feast of the Annunciation was celebrated as early as the fourth century. Its iconography was formed between the 2nd and the 15th centuries. The attributes of figures, their positions, and their arrangement make the scene easily recognizable. It is based on several sources, including the Gospel of Luke (1:26–1:38), the apocryphal Protoevangelium of James, and the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew, as well as hymnographic texts. According to these sources, six months after Elisabeth conceived her son, who would become John the Baptist, the archangel Gabriel visited the Virgin Mary to announce to her that she would soon become the mother of the Savior.

According to the story, Mary was spinning purple thread for a veil of the Temple in Jerusalem. Having heard the news, Mary asked how it could have happened if she “knew not a man”. The angel answered her by recounting the prophecy of the Immaculate Conception by the Holy Spirit. When Mary expressed her readiness to fulfill the will of God, the Incarnation also took place.

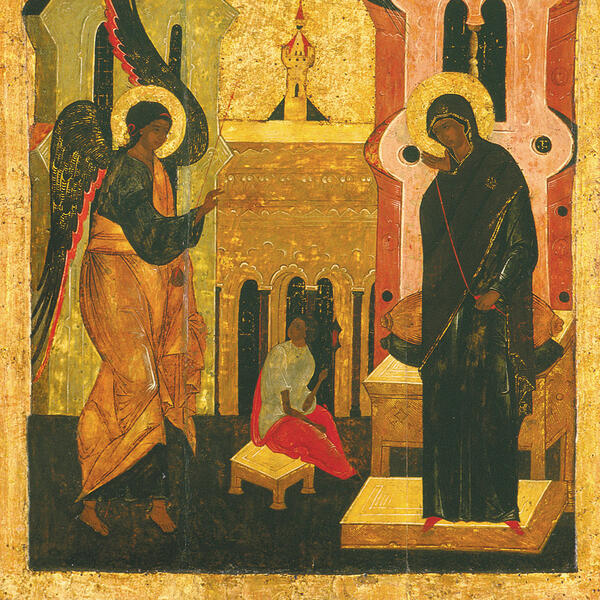

Instead of Joseph’s house, such icons usually depicted the buildings and landscapes referring to the image of the New Jerusalem, thus emphasizing the role of the Virgin Mary as the Human Temple. The purple thread on her spinning wheel indicates both Mary’s sacred work and the creation of Christ’s flesh. The throne behind Mary is an allusion to several symbols, including the Throne of Solomon, the Old Testament prophecies, the Throne of God, and the symbol of the Virgin Mary — the altar of the Everlasting Word.

Some of the details vary from one version to another. The Everlasting Virgin may either fold her hands in prayer, express an embarrassment by the grace of God (with one hand pressed to her chest and the other open hand stretched out toward the Archangel) or the submission to the will of God (with one hand in the center of her chest and the other stretched out toward the viewer). Sometimes, the icons also feature the image of the Christ child against his mother’s womb and a pigeon symbolizing the Holy Spirit.

By the late 13th — early 14th century, icon painters started adding a figure of a young woman spinning. She might be a witness of the miracle — one of the eight virgins chosen to weave the veil for the temple, or a serving maid. This figure is often associated with the ancient image of a Moirai spinning the thread of life.

The Annunciation was the first tiding of joy for people since the fall from grace and the first Christian act of redemption. The scene of the conversation between the Virgin Mary and the Messenger of God is filled with particular solemnity. Both figures look majestic and dignified. Their monumental nature is emphasized visually with the help of tower-like buildings in the background.

This image was the main icon of a small parish Annunciation Church. Its iconography is unique: the icon painter might have had a collection of outline drawings which he used to create this iconographic variation.

According to the story, Mary was spinning purple thread for a veil of the Temple in Jerusalem. Having heard the news, Mary asked how it could have happened if she “knew not a man”. The angel answered her by recounting the prophecy of the Immaculate Conception by the Holy Spirit. When Mary expressed her readiness to fulfill the will of God, the Incarnation also took place.

Instead of Joseph’s house, such icons usually depicted the buildings and landscapes referring to the image of the New Jerusalem, thus emphasizing the role of the Virgin Mary as the Human Temple. The purple thread on her spinning wheel indicates both Mary’s sacred work and the creation of Christ’s flesh. The throne behind Mary is an allusion to several symbols, including the Throne of Solomon, the Old Testament prophecies, the Throne of God, and the symbol of the Virgin Mary — the altar of the Everlasting Word.

Some of the details vary from one version to another. The Everlasting Virgin may either fold her hands in prayer, express an embarrassment by the grace of God (with one hand pressed to her chest and the other open hand stretched out toward the Archangel) or the submission to the will of God (with one hand in the center of her chest and the other stretched out toward the viewer). Sometimes, the icons also feature the image of the Christ child against his mother’s womb and a pigeon symbolizing the Holy Spirit.

By the late 13th — early 14th century, icon painters started adding a figure of a young woman spinning. She might be a witness of the miracle — one of the eight virgins chosen to weave the veil for the temple, or a serving maid. This figure is often associated with the ancient image of a Moirai spinning the thread of life.

The Annunciation was the first tiding of joy for people since the fall from grace and the first Christian act of redemption. The scene of the conversation between the Virgin Mary and the Messenger of God is filled with particular solemnity. Both figures look majestic and dignified. Their monumental nature is emphasized visually with the help of tower-like buildings in the background.

This image was the main icon of a small parish Annunciation Church. Its iconography is unique: the icon painter might have had a collection of outline drawings which he used to create this iconographic variation.