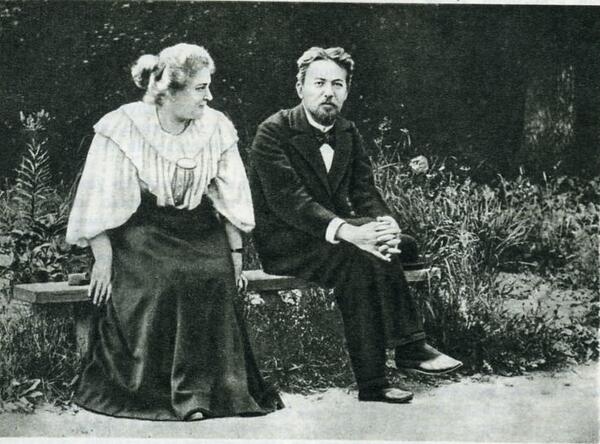

The photograph depicts Anton Pavlovich Chekhov and Lidiya Stakhievna Mizinova, or Lika, as she was known among friends.

One of the most enduring myths that emerged during Chekhov’s lifetime was the one about the writer’s irrevocable love for Lika. How, why could the myth emerge when the characters were still alive, and why was it not dispelled for so long?

A major role was played by the comedy “The Seagull”, where a lot of details were identical to those in Lika’s fate: the desire to go on stage, the romance with the writer, and the birth of a child. For Lydia Stakhievna “The Seagull” was inseparable from her own destiny. In 1934, a book by Yuri Sobolev “Chekhov” from the series “Lives of Great People” came out. It contained a number of quotes from Mizinova’s letters addressed to Chekhov. They gave a lot of insight into their relationship, but it was only them who knew the whole truth.

As his contemporaries recalled, Anton Pavlovich was shy, very reserved and “discreet in everything that concerned his intimate feelings”; “he did not share the deepest and most serious feelings in his soul with those close to him. As a man of great substance and modesty, he loved the loneliness of feeling and the loneliness of thought.”

Chekhov enjoyed great success with women, but did not like to talk about it. Many contemporaries, including Lika, took it for callousness and inability to experience strong feelings. Chekhov kept himself at ease and withdrawn at the same time, a rare and purely Chekhovian quality; his jokes would divert him from serious explanations. He invented admirers for Lika: Trofimov, Pryshchikov, Pet’ka — and mocked them in his letters. Displays of his true feelings were drowned in his games and jokes. In this manner, it was not Chekhov’s insensitivity, but rather his masculine magnanimity, his unwillingness to highlight his victory in order to preserve the joy and ease of communication with Lika.

In 1898, Lydia Mizinova sent Chekhov a photo of herself to Yalta from Paris. She signed it as follows,

One of the most enduring myths that emerged during Chekhov’s lifetime was the one about the writer’s irrevocable love for Lika. How, why could the myth emerge when the characters were still alive, and why was it not dispelled for so long?

A major role was played by the comedy “The Seagull”, where a lot of details were identical to those in Lika’s fate: the desire to go on stage, the romance with the writer, and the birth of a child. For Lydia Stakhievna “The Seagull” was inseparable from her own destiny. In 1934, a book by Yuri Sobolev “Chekhov” from the series “Lives of Great People” came out. It contained a number of quotes from Mizinova’s letters addressed to Chekhov. They gave a lot of insight into their relationship, but it was only them who knew the whole truth.

As his contemporaries recalled, Anton Pavlovich was shy, very reserved and “discreet in everything that concerned his intimate feelings”; “he did not share the deepest and most serious feelings in his soul with those close to him. As a man of great substance and modesty, he loved the loneliness of feeling and the loneliness of thought.”

Chekhov enjoyed great success with women, but did not like to talk about it. Many contemporaries, including Lika, took it for callousness and inability to experience strong feelings. Chekhov kept himself at ease and withdrawn at the same time, a rare and purely Chekhovian quality; his jokes would divert him from serious explanations. He invented admirers for Lika: Trofimov, Pryshchikov, Pet’ka — and mocked them in his letters. Displays of his true feelings were drowned in his games and jokes. In this manner, it was not Chekhov’s insensitivity, but rather his masculine magnanimity, his unwillingness to highlight his victory in order to preserve the joy and ease of communication with Lika.

In 1898, Lydia Mizinova sent Chekhov a photo of herself to Yalta from Paris. She signed it as follows,